Introduction to

Theodoret of Cyrus

Background (excerpt from Catholic Encyclopedia online)

Theodoret [Theodoretus], Bishop of Cyrus and theologian, [a Greek] born at Antioch in Syria about 393; died about 457.

He says himself that his birth was an answer to the prayers of the monk Macedonius ("Hist. rel.", IX; Epist. lxxi). On account of a vow made by his mother he was dedicated from birth to the service of God and was brought up and educated by the monks Macedonius and Peter. At a very early age he was ordained lector. In theology he studied chiefly the writings of Diodorus of Tarsus, St. John Chrysostom, and Theodore of Mopsuestia.

Theodoret was also well trained in philosophy and literature. He understood Syriac as well as Greek, but was not acquainted with either Hebrew or Latin. 1 When he was twenty-three years old and both parents were dead, he divided his fortune among the poor (Epist. cxiii; P.G., LXXXIII, 1316) and became a monk in the monastery of Nicerte not far from Apamea, when he lived for seven years, devoting himself to prayer and study.

Monk becomes Bishop

Much against his will about 423 he was made Bishop of Cyrus [i.e., 'Cyrrhus', a Syrian city about 2 days journey from Antioch]. His diocese included nearly 800 [Syriac-speaking] parishes and was suffragan of Hierapolis. A large number of monasteries and hermitages also belonged to it, yet, notwithstanding all this, there were many heathen and heretics within its borders. Theodoret brought many of these into the Church, among others more than a thousand Marcionites.

He also destroyed not less than two hundred copies of the "Diatessaron" of Tatian, which were in use in that district ("Haeret. fab.", I, xix; P.G., LXXXIII, 372).

He often ran great risks in his apostolic journeys and labours; more than once he suffered ill-usage from the heathen and was even in danger of losing his life. His fame as a preacher was widespread and his services as a speaker were much sought for outside of his diocese; he went to Antioch twenty-six times. Theodoret also exerted himself for the material welfare of the inhabitants of his diocese. Without accepting donations (Epist. lxxxi) he was able to build many churches, bridges, porticos, aqueducts, etc. (Epist. lxxxi, lxxviii, cxxxviii).

The Nestorian controversy

Towards the end of 430 Theodoret became involved in the Nestorian controversy. In conjunction with John of Antioch he begged Nestorius not to reject the expression 'Theotokos' as heretical (Mansi, IV, 1067). Yet he held firmly with the other Antiochenes to Nestorius [the pupil of Theodore of Mopsuestia] and to the last refused to recognize that Nestorius taught the doctrine of two persons in Christ.

Until the Council of Chalcedon in 451 he was the literary champion of the Antiochene party. In 436 he published his 'Anatrope' (Confutation) of the Anathemas of Cyril to which the latter replied with an Apology (P.G., LXXVI, 392 sqq.).

At the Council of Ephesus (431) Theodoret sided with John of Antioch and Nestorius, and pronounced with them the deposition of Cyril and the anathema against him. He was also a member of the delegation of "Orientals", which was to lay the cause of Nestorius before the emperor but was not admitted to the imperial presence a second time (Hefele-Leclerq, "Hist. des Conc.", II, i, 362 sqq.).

The same year he attended the synods of Tarsus and Antioch, at both of which Cyril was again deposed and anathematized. Theodoret after his return to Cyrus continued to oppose Cyril by speech and writing.

The symbol (Creed) that formed the basis of the reconciliation (c. 433) of John of Antioch and others with Cyril was apparently drawn up by Theodoret (P.G., LXXXIV, 209 sqq.), who, however, did not enter into the agreement himself because he was not willing to condemn Nestorius as Cyril demanded.

It was not until about 435 that Theodoret seems to have become reconciled with John of Antioch, without, however, being obliged to agree to the condemnation of Nestorius (Synod. cxlvii and cli; Epist. clxxvi). The dispute with Cyril broke out again when in 437 the latter called Diodorus of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia the real originators of the Nestorian heresy. Theodore entered the lists in their defence. The bitterness with which these polemics were carried on is shown both by the letter and the speech of Theodoret when he learned of the death in 444 of the Patriarch of Alexandria (Epist. clxxx).

House Arrest, Persecution

The episcopate of Dioscurus, the successor of Cyril, was a period of much trouble for Theodoret. Dioscurus, by the mediation of Eutyches and the influential Chrysaphius, obtained an imperial edict which forbade Theodoret to leave his diocese (Epist. lxxix-lxxxii). In addition Theodoret was accused of Nestorianism (Epist. lxxxiii-lxxxvi); in answer to this attack he wrote his most important polemical work, called "Eranistes".

Theodoret was also considered the prime mover of the condemnation of Eutyches by the Patriarch Flavian. In return Dioscurus obtained an imperial decree in 449 whereby Theodoret was forbidden to take any part in the synod of Ephesus (Robber Council of Ephesus). At the third session of this synod Theodoret was deposed by the efforts of Dioscurus and ordered by the emperor to re-enter his former monastery near Apamea.

Redemption, Capitulation

Better times, however, came before long. Theodoret appealed to Pope Leo who declared his deposition invalid, and, as the Emperor Theodosius II died the following year (450), he was allowed to re-enter his diocese. In the next year, notwithstanding the violent opposition of the Alexandrine party, Theodoret was admitted as a regular member to the sessions of the Council of Chalcedon, but refrained from voting. At the eighth session (26 Oct., 451), he was admitted to full membership after he had agreed to the anathema against Nestorius; probably he meant this agreement only in the sense: in case Nestorius had really taught the heresy imputed to him (Mansi, VII, 190).

It is not certain whether Theodoret spent the last years of his life in the city of Cyrus, or in the monastery where he had formerly lived. There still exists a letter written by Pope Leo in the period after the Council of Chalcedon in which he encourages Theodoret to co-operate without wavering in the victory of Chalcedon (P.G., LXXXIII, 1319 sqq.).

The writings of Theodoret against Cyril of Alexandria were anathematized during the troubles that arose in connexion with the war of the Three Chapters.

- http://www.newadvent.org (Entry: Theodoret)

Footnotes:

1. "unacquainted with Hebrew and Latin.."(?)

This statement must be seriously challenged: Theodoret's lack of experience with Hebrew is not strictly plausible: he must have spoken fluent Syriac, and could hardly have overseen the replacement of the Diatessaron with Syriac translations of the Gospels, without having to face issues surrounding Hebraisms and Aramaisms in the NT.

Also, to say he was unaquainted with Latin seems implausible also, and appears to based on simple lack of information: Although born a Greek and living in the Eastern half of the Empire, he was after all educated by monks, and must have had extensive knowledge of both church history and Latin fathers and documents. Latin had been the official language of most of the Empire for centuries, and all government documents in Latin jurisdictions would be published in that language. It seems unlikely that his education would have entirely neglected Latin, or that he would have had no acquantance whatever with Latin.

The linguistic situation must be understood to be very similar to the modern situation in Canada: One small province would remain Greek speaking, but all major economic centers of business such as Constantinople would be bilingual, as would all border areas between the region of Greece/Turkey and the rest of the Empire. Just as in Canada today, higher level government employment would virtually require working skills in both official languages. In those days, this would also be true of the clergy.

Steven Avery notes that the "no Latin" argument is far from convincing, and quotes Schaff:

"...Theodoret was familiar with Greek, Syriac, and Hebrew, but is said to have been unacquainted with Latin.16 Such I presume to be an inference froth a passage in one of his works17 in which he tells us,

"The Romans indeed had poets, orators, and historians, and we are informed by those who are skilled in both languages that their reasonings are closer than the Greeks` and their sentences more concise. In saying this I have not the least intention of disparaging the Greek language which is in a sense mine,18 or of making an ungrateful return to it for my education, but I speak that I may to some extent close the lips and lower the brows of those who make too big a boasting about it, and may teach them not to ridicule a language which is illuminated by the truth."

But it is not clear from these words that Theodoret had no acquaintance with Latin. His admiration for orthodox Western theology as well as his natural literary and social curiosity would lead him to learn it. In the Ecclesiastical History (III. 16) there is a possible reference to Horace."

16. Letter cxxx, 7.

17. Groecarum affectionum curatio (843).

18. To a Syrian it would not be literally the mother tongue but was possibly acquired in infancy.

- Schaff, The Life and Writings of the Blessed

Theodoretus, Bishop of Cyrus, Prolegomena

As to Theodoret's experience with Hebrew, Steven Avery quotes several conflicting authorities, but the following is of note:

"...the Hebrew text was cited with some critical acumen in the commentaries of Theodoret."

- M. J. Mulder, H. Sysling,

Mikra: Text, Translation, Reading,

and Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible

in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity

(1984) p. 772

(referencing Guinot and Elliott)

The opposing view, as represented at least by interpreters like Robert C. Hill, seems far less credible, because of its myopic focus. According to Randall L. McKinion (Shepherds Theological Seminary, NC), "Theodoret’s exegetical deficiencies were compounded, according to Hill, by his. ignorance of the Hebrew language", but as McKinion points out, this is all based on Hill assuming that Theodoret has misunderstood the "Apocalyptic" nature of Daniel. To quote McKinnion again, (book review: Theodoret of Cyrus: Commentary on Daniel)

"Theodoret’s exegetical deficiencies were compounded, according to Hill, by his ignorance of the Hebrew language. Being bound to a Greek version of the book, at times Theodoret follows an improper understanding of the text that would have been easily corrected with a cursory knowledge of the Hebrew term in question. Such issues are explained appropriately in Hill’s notes (e.g., 151 n. 130)."

- McKinion, pg 3-4, Review

But of course Theodoret is not "bound to a Greek version of Daniel" so much as he is freely adopting the church sanctioned authorized translation, as a result of a longstanding battle over the question of the relative truth and accuracy of the LXX (Greek) text versus the allegedly mutilated Jewish (Hebrew) version.

Hill assumes Theodoret's reading is coloured by his NT view of Daniel as a Prophet. This is hardly 'evidence' that Theodoret doesn't know Hebrew. One could make the very same criticisms of modern (Christian) scholars who have devoted lifetimes to the study of Hebrew!

Theodoret and the Diatessaron

Theodoret was a vigorous and careful protector of the Greek text of the New Testament. It is remarkable that early in his career as a bishop, he gathered up and destroyed all the copies of the Diatessaron, an early but flawed popular 'harmony' of the Gospels translated into (or composed in) the Syriac language, a sister-language of the older Aramaic of Jesus, and Hebrew.

Theodoret's diocese consisted of over 800 parishes (local churches) all mostly Syriac-speaking. This area was close to the NT 'Galilee', or what is now modern Lebanon and Syria.

One of the main textual differences or 'faults' of the Diatessaron is that it omits John 7:53-8:11 in its blending in of the Gospel of John with an earlier 'Synoptic Harmony' of the first three gospels.

That Theodoret met little resistance in making this sweeping change in the early 400s suggests that the Syriac church at that time freely acknowledged the priority and accuracy of the Greek New Testament, and desired to have direct translations of same in their native language.

'Early in his bishopric he made an inspection trip through his diocese. He reports:

"I myself found more than two hundred copies of [the Diatessaron] in reverential use in the churches of our diocese, and all of them I collected and removed, and instead of them I introduced the gospels of the four evangelists."'

- reported in Barbara Aland, Earliest Gospels, p.56

Theodoret and Theodore of Mopsuestia

Of interest is the following anecdote given in Schaff (NPNF, Theodoret):

' Garnerius is of opinion that the work might with propriety be entitled A History of the Arian Heresy; all other matter introduced he views as merely episodic.(see Theod. Ed. Migne. V. 282.) He also quotes the letter ( Ep. XXXIV) of Gregory the Great in which the Roman bishop states that,

"the apostolic see refuses to receive the History of 'Sozomenus' (sic) inasmuch as it abounds with lies, and praises Theodore of Mopsuestia, maintaining that he was up to the day of his death, a great Doctor."

"Sozomen" is supposed to be a slip of the pen, or of the memory, for "Theodoret". But, if this be so, "multa mentitur" is an unfair description of the errors of the historian [Theodoret]. Fallible he was, and exhibits failure in accuracy, especially in chronology, but his truthfulness of aim is plain.'

- NPNF, Prologomena, Theodoret

Theological Disputes and Liturgical Practices

What is remarkable about this notice, is that Theodore of Mopsuestia, or rather his liturgical commentary on John (now lost), apparently excluded any discussion of the Pericope de Adultera (Jn 8:1-11). This is noted in an anonymous secondary hand next to the passage in a late (12th cent.) copy of John.

Although Theodoret was an enthusiastic student and defender of Theodore of Mopsuestia, he plainly accepted John 8:1-11 as Holy Scripture. It would have been impossible for him not to have been aware of the question, thirty years after St. Jerome had published his Latin Vulgate under the authority of the Bishop of Rome, which included the verses. His apparent silence, combined with the passage's acceptance all over Europe must be taken as assent.

One explanation is that Theodoret was well aware of why Theodore of Mopsuestia skipped over the passage, namely that it was simply not read on Pentecost, but relegated from early times to feast days in October.

It was not heard by the congregation during Pentecost, and hence it could not be commented upon in a public commentary in the usual place. Even if this was not the original historical reason for the omission of the passage in the earliest manuscripts, it would certainly be a natural assumption in Theodoret's time, when the lectionary practices were long established.

In passing, we may note that Theodore of Mopsuestia was a controversial character in Theodoret's time (early 400s), and classed by significant parties as stongly heretical. One of the reasons might be an association of Theodore of Mopsuestia with the omission of the Pericope de Adultera, which might have been misunderstood by many.

After St. Augustine among the Latins had characterized those who omitted the verses as "...enemies of the true faith", it would be difficult for many not to suspect anyone who seemed to ignore the verses of being part of a heretical conspiracy. That Theodore of Mopsuestia is in fact cited by an unknown person in the margin of a later manuscript as supporting omission lends credence to the possibility that this misunderstanding arose and lingered quite a long time.

Historical Background

for Constantine

Photius

The Patriarch

Photius (Photios):

Patriarch of Constantinople

Photius (Photios) Patriarch of Constantinople

Patriarch of Constantinople (858-867 and 877-886, feast day February 6), is considered the greatest of all Byzantine patriarchs. Extremely learned in ancient Greek literature and philosophy as well as Christian theology, he was originally professor of philosophy at the famous University of Constantinople -- the first university (or "higher school") to be established in medieval Europe, at a time when the West was still stuck in the mire of the barbaric Dark Ages.

Photios was perhaps responsible for a new codification of canon (church) law, the Collection of 14 Titles, and probably for a new legal code, the Epanagoge, which spelled out a new importance for the patriarch with respect to the Emperor.

Photius Converts the Slavs

But he is perhaps best known for his leading role in the conversion of the Slavic peoples. It was Photios who, correctly understanding the inner psychology of the semi-barbaric Moravian Slavs (in today's Czechoslovakia), dispatched to convert them in 862, at their request, the Apostles to the Slavs, Cyril (or Konstantinos) and his brother Methodios, two Greeks from Thessalonike learned in the Slavonic language and, most important, to translate the Greek liturgy into Slavonic.

Rome (850 A.D.) Witholds Liturgy from Slavs

In this way Photios bound them to Constantinople instead of to Rome which was also seeking to convert them but would not permit the liturgy to be translated into Slavonic.

Photios was also primarily responsible for converting the Bulgars, then wavering between Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy. It was Photios' conversion of the Moravians and Bulgars through the work of Cyril and Methodios that later led to the Byzantine conversion of the Russian Slavs.

Falsely Branded a Heretic by Latin Church

In addition, Photios established, or reorganized, the patriarchal school in Constantinople for the education of priests in literature and philosophy as well as in theology. (It is the direct ancestor of the modern patriarchal school at Halki). Until publication of Father Dvornik's recent work on Patriarch Photios, he was considered by the Roman Church (not of course by the Orthodox for whom he has always been a great ecclesiastical hero) as the arch-heretic, the one most responsible for originating the schism or split between the Churches of Rome and Constantinople, the first to formulate Orthodox Greek charges against innovations (kenotomies) in doctrine and practices of the Roman Church.

But these were usually teachings propounded not so much by the Latins of Rome as by the recently converted Germans, who had sent missionaries into Bulgaria. In particular they taught the doctrine of the filoque (that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and Son), contrary to explicit pronouncements of the early Ecumenical Councils that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father (alone). (Ekporevetai ek tou Patros). The latter is the view of the Orthodox, a belief considered necessary in order to preserve the unitary nature of God -- since there can be only one fundamental archic source for the Godhead, not two. If there are two sources, there would in effect be two Gods.

Philostorgius rescued by Photius

Philostorgius (364-425 A.D.) was a church historian like Eusebius (320 A.D.), and set out with the pretense at least of continuing Eusebius' Church History. Eusebius' history ends around 320 A.D. with the victory of Constantine over Licinius (324 A.D.). Philostorgius' Ecclesiastical History covers the next hundred years in twelve books (two volumes).

Although the work itself no longer survives, Photius, the Patriarch of Constantinople (circa 853 A.D.) saw its value, and made a surprisingly thorough summary ('Epitome') of its contents for us. Although Photius was obviously orthodox, he himself was apparently responsible for the removal of the term "Filioque" from the Nicene Creed.

Photius himself however liberally criticizes Philostorgius as an impious heretic throughout, and so colors his own work. Alerted to these biases, the historian can readily sift out the superfluous remarks and work through the surviving historical information

Philostorgius

Philostorgius: Church Historian

Philostorgius (364-425 A.D.) was a church historian like Eusebius (320 A.D.), and set out at least with the pretense of continuing Eusebius' Church History. Eusebius' history ends around 320 A.D. with the victory of Constantine over Licinius (324 A.D.). Philostorgius covers the next hundred years in twelve books (two volumes).

Arian Heretic

Unfortunately, Philostorgius was of the Arian party, a group which denied the Godhead of Jesus and had their own explanation of Jesus as a being of lesser status. By this time (425 A.D.) such a position had been debated for 100 years and settled by ecclesiastical synods in favour of the Trinity and against the Arians.

This would have been less important, except that Philostorgius energetically defended the views of the Arian party and those now classed as heretics. Philostorgius' Ecclesiastical History was probably 'banned' and destroyed, and no longer survives. It is probably fair to say that this is partly his own fault. He could have been more even-handed in his History and saved the debating and apologetics for a separate work.

Philostorgius also suffers from being gullible and superstitious concerning legendary and 'miraculous' events. But this does not seriously impede the work of historians or the value of his other historical data:

"Philostorgius would seem to have been a person possessed of a considerable amount of general information, and he has inserted in his narrative many curious geographical and other details about remote and unknown countries, and more especially about the interior of Asia and Africa. "

-translator's notes (see below)

A Critically Important Work

In spite of Philostorgius' bias, his work remains of great value because it provides information about the critical period between 325-425 A.D. that we would not have otherwise, such as the details of the debates over Arianism and the identity and activity of the various parties.

Philostorgius rescued by Photius

Although the work itself no longer survives, Photius, the Patriarch of Constantinople (circa 853 A.D.) saw its value, and made a surprisingly thorough summary ('Epitome') of its contents for us. Although Photius was obviously orthodox, he himself was apparently responsible for the removal of the term "Filioque" from the Nicene Creed.

Photius himself however liberally criticizes Philostorgius as an impious heretic throughout, and so colors his own work. Alerted to these biases, the historian can readily work around the superfluous remarks and sift the surviving historical information.

Philostorgius and John 8:1-11

Two of the most remarkable pieces of information are found in Philostorgius, which have a bearing upon the possible excising of John 7:53-8:11, or the perpetuation of this omission.

'Taken in Adultery'

(1) Philostorgius informs us of the death of Constantine's son and queen (Book II chapt 4), in which Constantine orders the queen to be 'steamed to death' for adultery. Both Constantine's intense anger and potential for violence, and his extreme emotional response to adultery are evident in this anecdote.

Book II: Chapter 4

"Philostorgius asserts that Constantine was induced by the fraudulent artifices of his step-mother to put his son Crispus to death; and afterwards, upon detecting her in the act of adultery with one of his Cursores, ordered the former to be suffocated [to death] in a hot bath.

He adds, that long afterwards Constantine was poisoned by his brothers during his stay at Nicomedia, by way of atonement for the violent death of Crispus."

- Photius, Epitome (Book II, Ch.4)

Plainly, Constantine's disposition toward the Pericope de Adultera (Jn 7:53-8:11) may have been understandably tainted by his experience here.

This incident in Constantine's life occurred in 324 A.D., only one year before the famous Council of Nicea. It can hardly be considered a mere theoretical question or a part of Constantine's distant past.

(2) Philostorgius relates the remarkable circumstances of the translation of the Gothic Version of the Bible (Book II chapt 5), in which he notes that two whole books of the Bible (probably 1st/2nd Samuel & Kings in the LXX) were left out entirely by the translator, in spite of their importance (Bishop Urphilas was appointed just one year after the death of Eusebius and three years after Constantine).

Book II: Chapter 5

...This was done "because they are a mere narrative of military exploits, and the Gothic tribes were especially fond of war, and were in ...need of restraints to check their military passions."

- Photius, Epitome (Book II, Ch.5)

Whether or not Constantine or Eusebius (or both) had actually prearranged and ordered this omission, it was a decision done at the highest level (the bishops), and Constantine most certainly had a special interest in the Goths.

It is hard to imagine that either Constantine or Eusebius were uninformed about Bishop Urphilas' plan to omit the books of Kings, or that it hadn't been previously discussed. After all, Philostorgius and Photius have knowledge of it, and don't even think it is very remarkable.

When all is said and done, it is evident that the bishops and translators were willing to pragmatically omit portions of Holy Scripture they deemed 'unsuitable' when providing translations into other languages in this period. This has great bearing on the variants in other 'versions' (translations) such as the Syriac Peshitta and the Armenian etc. , and especially upon the reliability of copies of the Greek NT from this period, like Codex Vaticanus and Sinaiticus.

The Roman Church apparently continued this practice of denying people religious texts "for their own good", well into the 9th century, since it was they who refused the Slavs a translation of the liturgy, a stubborn political error which caused the Slavs to turn to the Greek Orthodox instead..

Elijah left Hanging

And the books of the Kings are not an insignificant portion of Holy Scripture: these contain the stories of Elijah and Elisha the prophets, who are referenced repeatedly in the New Testament. Dropping these books leaves large parts of the Gospel story unexplained and possibly even incomprehensible.

Philostorgius then, through the hands of Photius, preserves for us key information on events and attitudes for this critical period in which both Codex Sinaiticus and Vaticanus were produced, probably by under the direction of Eusebius at the orders of Emperor Constantine.

For more on Philostorgius see our article here:

Philostorgius <- - Click Here.

Vaticanus and

Sinaiticus

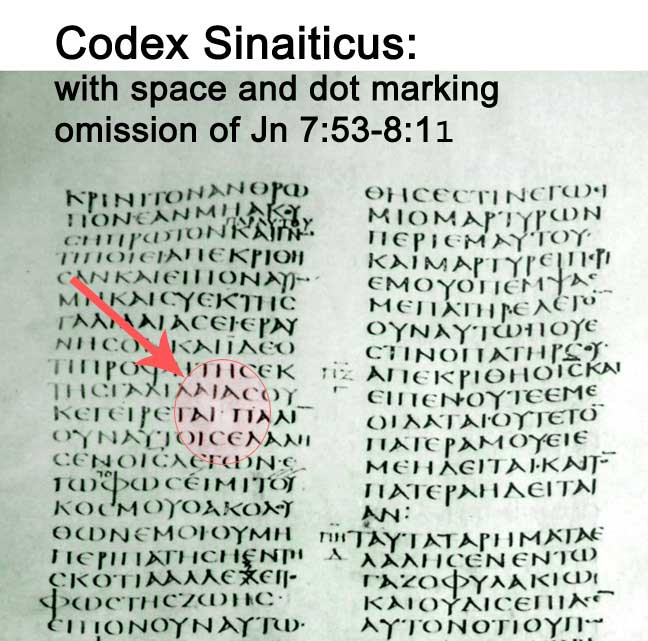

Codex Sinaiticus (330-400 A.D.):

A 'Great Bible' from the Constantine Period

The key page of Codex Sinaiticus above, shows the place-holder technique of space and dot, marking the omission of John 7:53-8:11. Normally, no spaces are left between words, or even sentences, and sometimes a word will be split in half and continued on the next line without any notice.

This practice of using dots to signify variants (along with other markings) was carried on by Alexandrian scribes for at least two centuries (150-350 A.D.). At this time, the complex accenting system of the Middle Ages was virtually non-existant, and single dots were not used as often for other purposes, like accenting, breathing notes or punctuation.

A single dot appears in other places on the page as well, however in some cases, like the one in the middle of line 11 column 2, they were added later by the corrector or another hand. The important observation for the dot of interest (line 11, column 1) is that it is definitely by the original hand. The necessary space was provided for the dot by the scribe writing the letters. This special dot then, was combined into the text, and was probably in the master-copy the scribe was working from.

Tischendorf was well aware of this feature of Sinaiticus, and he included the mark in his facsimile edition, for which he had prepared a special type-face to handle the many peculiarities of the manuscript.

For more information on text-critical marks on manuscripts, see here:

Top Ten MSS for John < - - Click Here.

Codex Vaticanus (330-360 A.D.):

A 'Great Bible' from Constantine's time

The Nature and Reliability of the 4th Century Uncials

In order to properly assess the value of Codex Vaticanus (B) and Sinaiticus (א), we need to know about what they are, and who made them. Just after the last Great Persecution of Christians by Diocletus (311 A.D.), Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity and legalized it (313 A.D.). Edward Miller has offered a good background description of what happened next:

"Constantine...gave the celebrated order to Eusebius, probably between 330-340 A.D., to send him 50 magnificent copies of the Holy Scriptures. They were to be written on the best vellum (calfskin) by skillful penmen,and in a form well fitted for [church] use. Orders were also issued to the provincial Governor to supply the working materials, and the work was to proceed with all possible speed. Two carriages were given to Eusebius for transport to Constantinople, and they were sent under charge of a deacon. 1

There are several reasons for supposing that B and (א) were among the 50 MSS. They are dated by experts to about the period of Constantine's letter. Tischendof and Scrivener believe the scribe of B wrote six consecutive pages in (א) . Both manuscripts are unrivalled for quality of vellum and calligraphy, as we would expect from MSS made to Imperial Order out of Imperial resources. They are also 'sister MSS' according to their significant agreement in variants. They abound in omissions and show carelessness typical of a 'rush job'. Even the corrector (the 'Diothotess') shows similar carelessness.

It is expressly stated in (א) that it was collated with an ancient MSS corrected by Pamphilus after Origen's Hexapla. And Caesaria was where the MSS of Origen and Pamphilus would be found.

There is then good cause for the opinion that these two MSS were executed by order of Constantine, and they show throughout the influence of Eusebius and Origen, whose work was housed at the library of Pamphilus in Caesarea, where they were most likely made."

(E. Miller, A Guide to the Textual Criticism of the NT, p 81-83)

Footnotes:

1. Eusebius sent them "τρισσα και τετρασσα". (Vit. Const., IV.37). There are several interpretations possible here: (1)"in triple or quadruple sheets" - but in that case it would have been probably "τριπλοα και τετραπλοα". (2) "written in 3 or 4 vertical columns"(so Canon Cook), which would exactly describe B and (א), only a preposition is missing to turn the adjectival into adverbial expression. (3) combined with "πεντηκοντα σωματια εν διξθεραις εγκατασκευοις (c. 36), "..we sent abroad the collections [of writings] in richly adorned cases, three or four in a case" (So Archdeacon Palmer, quoted by Scrivener). After examining the letters, I am convinced that Palmer is right. (see Cook, Revised Version p.162-163, & Scrivener p.513 footnote).

The Origin of Codex Sinaiticus

It may be argued that Codex Sinaiticus (Aleph) was not one of the "50 Bibles" ordered by Constantine. It is plausible that it was an early 'reject' from this shipment, abandoned because of its inferior quality (lack of suitable editing) or through a change of plan in the details of the execution.

It may also be that this manuscript was executed independantly prior to the order, and hence was abandoned on that basis, once the order was placed. In that case, some would argue for the independant witness of its text to that of Vaticanus.

But these minor questions and disputes are secondary to our point here, since we are not arguing that Constantine and/or Eusebius were the originators of the omission.

Other textual evidence, like that of P66 and P75 indicates that the original omission may have occurred centuries earlier and for quite different reasons than those behind its later adoption by Constantine and Eusebius.

Summary:

We may now make the following basic points:

(1) Constantine executed his queen for a crime involving adultery.

(2) Bishops like Ufalas, practically contemporary with Eusebius and Constantine were willing to omit sacred texts being provided to the people "for their own good".

(3) Eusebius and Constantine produced Codex Vaticanus and were possibly involved with Sinaiticus.

(4) These manuscripts leave out the Pericope de Adultera, and the probability is that Constantine and Eusebius adopted the omission of the passage knowingly and with purpose.

(5) No one openly talked about this "official omission" (or its continuation) intil 50 years after Constantine's death (in 337 a.d.)

(6) Then everyone from the bishop of Rome on down, and from Jerusalem over to Spain spoke up and defended the authenticity of the passage, and complained about manuscripts omitting it.

(7) It was finally adopted as Holy Scripture without protest all over the empire for the next thousand years.

Theodoret on Constantine

Excerpt from Historia Ecclesiastica

Chapter IX.

The Epistle of the Emperor Constantine,

concerning the matters transacted at the Council,

addressed to those Bishops who were not present.The great emperor also wrote an account of the transactions of the council to those bishops who were unable to attend. And I consider it worth while to insert this epistle in my work, as it clearly evidences the piety of the writer:

"Constantinus Augustus to the Churches.

Viewing the common public prosperity enjoyed at this moment, as the result of the great power of divine grace, I am desirous above all things that the blessed members of the Catholic Church should be preserved in one faith, in sincere love, and in one form of religion, towards Almighty God.

But, since no firmer or more effective measure could be adopted to secure this end, than that of submitting everything relating to our most holy religion to the examination of all, or most of all, the bishops, I convened as many of them as possible, and took my seat among them as one of yourselves; for I would not deny that truth which is the source of my greatest joy, namely, that I am your fellow-servant. Every point obtained its due investigation, until the doctrine pleasing to the all-seeing God, and conducive to unity, was made clear, so that no room should remain for division or controversy concerning the faith.

The commemoration of the most sacred paschal feast being then debated, it was unanimously decided, that it would be well that it should be everywhere celebrated upon the same day. What can be more fair, or more seemly, than that that festival by which we have received the hope of immortality should be carefully celebrated by all, on plain grounds, with the same order and exactitude? It was, in the first place, declared improper to follow the custom of the Jews in the celebration of this holy festival, because, their hands having been stained with crime, the minds of these wretched men are necessarily blinded. By rejecting their custom, we establish and hand down to succeeding ages one which is more reasonable, and which has been observed ever since the day of our Lord’s sufferings.

Let us, then, have nothing in common with the Jews, who are our adversaries. For we have received from our Saviour another way. A better and more lawful line of conduct is inculcated by our holy religion. Let us with one accord walk therein, my much-honoured brethren, studiously avoiding all contact with that evil way. They boast that without their instructions we should be unable to commemorate the festival properly. This is the highest pitch of absurdity. For how can they entertain right views on any point who, after having compassed the death of the Lord, being out of their minds, are guided not by sound reason, but by an unrestrained passion, wherever their innate madness carries them.

Hence it follows that they have so far lost sight of truth, wandering as far as possible from the correct revisal, that they celebrate a second Passover in the same year. What motive can we have for following those who are thus confessedly unsound and in dire error? For we could never tolerate celebrating the Passover twice in one year. But even if all these facts did not exist, your own sagacity would prompt you to watch with diligence and with prayer, lest your pure minds should appear to share in the customs of a people so utterly depraved. It must also be borne in mind, that upon so important a point as the celebration of a feast of such sanctity, discord is wrong.

One day has our Saviour set apart for a commemoration of our deliverance, namely, of His most holy Passion. One hath He wished His Catholic Church to be, whereof the members, though dispersed throughout the most various parts of the world, are yet nourished by one spirit, that is, by the divine will. Let your pious sagacity reflect how evil and improper it is, that days devoted by some to fasting, should be spent by others in convivial feasting; and that after the paschal feast, some are rejoicing in festivals and relaxations, while others give themselves up to the appointed fasts. That this impropriety should be rectified, and that all these diversities of commemoration should be resolved into one form, is the will of divine Providence, as I am convinced you will all perceive. Therefore, this irregularity must be corrected, in order that we may no more have any thing in common with those parricides and the murderers of our Lord.

An orderly and excellent form of commemoration is observed in all the churches of the western, of the southern, and of the northern parts of the world, and by some of the eastern; this form being universally commended, I engaged that you would be ready to adopt it likewise, and thus gladly accept the rule unanimously adopted in the city of Rome, throughout Italy, in all Africa, in Egypt, the Spains, the Gauls, the Britains, Libya, Greece, in the dioceses of Asia, and of Pontus, and in Cilicia, taking into your consideration not only that the churches of the places above-mentioned are greater in point of number, but also that it is most pious that all should unanimously agree in that course which accurate reasoning seems to demand, and which has no single point in common with the perjury of the Jews.

Briefly to summarize the whole of the preceding, the judgment of all is, that the holy Paschal feast should be held on one and the same day; for, in so holy a matter, it is not becoming that any difference of custom should exist, and it is better to follow the opinion which has not the least association with error and sin.

This being the case, receive with gladness the heavenly gift and the plainly divine command; for all that is transacted in the holy councils of the bishops is to be referred to the Divine will. Therefore, when you have made known to all our beloved brethren the subject of this epistle, regard yourselves bound to accept what has gone before, and to arrange for the regular observance of this holy day, so that when, according to my long-cherished desire, I shall see you face to face, I may be able to celebrate with you this holy festival upon one and the same day; and may rejoice with you all in witnessing the cruelty of the devil destroyed by our efforts, through Divine grace, while our faith and peace and concord flourish throughout the world.

May God preserve you, beloved brethren.

Chapter X.

The daily wants of the Church supplied by the Emperor,

and an account of his other virtues."Thus did the emperor write to the absent. To those who attended the council, three hundred and eighteen in number, he manifested great kindness, addressing them with much gentleness, and presenting them with gifts. He ordered numerous couches to be prepared for their accommodation and entertained them all at one banquet. Those who were most worthy he received at his own table, distributing the rest at the others.

Observing that some among them had had the right eye torn out, and learning that this mutilation had been undergone for the sake of religion, he placed his lips upon the wounds, believing that he would extract a blessing from the kiss.

After the conclusion of the feast, he again presented other gifts to them. He then wrote to the governors of the provinces, directing that provision-money should be given in every city to virgins and widows, and to those who were consecrated to the divine service; and he measured the amount of their annual allowance more by the impulse of his own generosity than by their need.

The third part of the sum is distributed to this day. Julian [the Apostate] impiously withheld the whole. His successor [Jovian] conferred the sum which is now dispensed, the famine which then prevailed having lessened the resources of the state. If the pensions were formerly triple in amount to what they are at present, the generosity of the emperor can by this fact be easily seen.

A Remarkable Event and Speech

I do not account it right to pass over the following circumstance in silence.

Some quarrelsome individuals wrote accusations against certain bishops, and presented their indictments to the emperor. This occurring before the establishment of concord, he received the lists, formed them into a packet which he sealed with his ring, and ordered them to be kept safely.

After the reconciliation had been effected, he brought out these writings, and burnt them in their presence, at the same time declaring upon oath that he had not read a word of them.

He said that the crimes of priests ought not to be made known to the multitude, lest they should become an occasion of offence, and lead them to sin without fear.

It is also reported that he [the Emperor Constantine] added that even if he were to detect a bishop "in the very act, committing adultery", [John 8:4!] he would throw his imperial robe over the unlawful deed, lest any should witness the scene, and be thereby injured.

Thus did he admonish all the priests, as well as confer honours upon them, and then exhorted them to return each to his own flock."

- Theodoretus of Cyrrhus,

Ecclesiastical History, Book I, ch. X

Analysis and

Conclusion

A Clever Story

Theodoret, after innocently praising the dead Emperor, puts the words of the Pharisees into his very mouth, and explains in his own way what must have happened behind closed doors at the council of Nicea.

Yet he has told the essence of the tale in such a way that any living emperor cannot find fault with him for it.

If this story is even remotely true, just imagine the scene:

what bishop could dare protest, sitting surrounded by his lavish gifts, and having received the promise that the Emperor himself would cover up any discovered adultery committed by a bishop, could protest about the omission of a mere 12 verses of John?

Theodoret has more than avenged John the Evangelist over the removal of his Holy Scripture, with this clever prose.

"What is whispered in secret, shall be shouted from the housetops!"

Several features of this anecdote require serious comment:

(1) Theodoret repeatedly emphasizes that Emperor Constantine rewarded (bribed) all the bishops who co-operated by participating in the council, and treated them like princes, lavishing them with gifts and funding.

(2) The men who cooperate in Constantine's scheme (i.e. keeping silence about the removal of the passage) are "honoured", recalling Christ's warning concerning preferring honour from men rather than God.

(2) The first statement in the story proper is eerily similar to the Latin father St. Augustine's overt comments regarding the PA both in sense, and even vocabulary (spoken probably a mere 10 years earlier): "...some persons of little faith, or rather enemies of the true faith, fearing, I think, lest their wives be given impunity to sin...(i.e. commit adultery)..."

(3) The exact phrase (in Greek!) taken from the passage, as rare an expression as one could possibly choose, and least ambiguous of all alternatives: "in the very act, committing adultery"

(4) The mention of the "burning of the writing", a stunning bit of poetic irony concerning the only passage in which Jesus is noted as writing. There is a previous famous story of a king burning a writing of a prophet, to no avail!

(5) The bizarre oath taken by Constantine before them all, a random and superfluous act, UNLESS it was a way of absolving himself from the charge of destruction of Holy Scripture. The oath assures his technical "innocence" in the matter.

(6) Historically, charges of "adultery" were in fact brought against various bishops and teachers by others and even by one another in the battle over doctrine. The need to silence such tactics and focus on the real issues was certainly acute.

(7) Nor can the lead-in or context be ignored:

(a) Theodoret prefaces it all (in chapter 9) with a letter from Constantine in which he equates himself in authority to a bishop(!) and with the other cooperating bishops asserts binding authority to conform to their council on all others! (far greater powers than a pope).

(b) Theodoret leads in with a story on Constantine's "charity" conspicuously OMITTING fallen women, abandoned wives, whores, and the typical "cast-offs" of society, but compensates by gifting VIRGINS and WIDOWS etc. This seems very likely historical, and would be difficult for opponents to criticize (rewarding virtue).

(c) Theodoret seems to carefully avoid any overt irony concerning either the charity, the dictatorial tendency, or the bribery and special indulgence offered to cooperating bishops. His language praises Constantine, yet his own reportage casts Constantine in a much less savoury light...

(8) All in all, Theodoret has just about said it all, without technically entrapping himself.

(9) This speaks to another issue, namely the likely reason why Greek bishops in the East were apparently silent for almost 100 years concerning what was obviously a raging controversy known from one end of the empire to the other. Namely, originally the bishops closely surrounding the emperor had given willing assent to remain silent through bribery, while those coming afterward must have also had to walk carefully under the very nose of succeeding emperors, all related to Constantine (beginning with his three later sons).