Page Index

Last Updated: Feb 19, 2009

1. Early Textual Criticism - oversimplification and naivity

2. Asterisks and Obelisks - four categories of usage

3. Early Classical Usage - the Ancient Alexandrian School: 180 B.C.

4. The Septuagint (LXX) - Early Christian LXX usage 240-400 A.D.

5. The Great Uncials: NT - N.T. Manuscript Correctors: 350 A.D.

6. The Byzantine Miniscules - The Last Days: 800 A.D. and beyond

7. Summary and Conclusion - The Meaning for John 8:1-11

8. Dr. Maurice Robinson on the Marks - leading expert explains. new!

Introduction

The marks in the margins of manuscripts have been brought up repeatedly in connection with the authenticity of John 7:53-8:11. It is important therefore that we have a good understanding of what these marks looked like, and what they were used for.

Like many other questions in textual criticism, the picture is more complex than one might suspect, and all is not what it seems. And, as in other areas of contention, the information is often tersely given or incomplete. Whether intentionally or not, this often enhances the presenter's position, and not legitimately.

Quick Definition:

obelus (a singular noun. plural = obeli)

from Latin obelus, from Greek obelos, a spit or skewer

1. A mark, either a dash (-) or a lemniscus (

), used in ancient MSS to indicate a doubtful or spurious passage.

2. A printing term: see obelisk.

Obelus is the preferred technical term for one of the categories of marks we will be examining. (The alternate term 'obelisk' is really just printer's slang.) What is commonly called an 'obelus' in the literature takes the following forms:

- a simple dash or horizontal stroke,

- a simple dash or horizontal stroke,

- or in very ancient times, a dagger or skewer.

- or in very ancient times, a dagger or skewer.

Also, the following symbols are often loosely called "obeli " in the critical literature:

- a lemniscus, (a horizontal line with two dots),

- a lemniscus, (a horizontal line with two dots),

- hypolemniscus, (line with one dot),

- hypolemniscus, (line with one dot),

However there is some doubt as to whether the classification of the lemniscus as a type of 'obelus' is accurate, or even appropriate, as we will see below in examining cases.

Asterisk is the term used to describe the following special mark:

- a 'star-like' decorative 'X' surrounded by dots.

- a 'star-like' decorative 'X' surrounded by dots.

This mark is often incorrectly interpreted as a type of 'obelus', or lumped together with other critical signs. However it has its own distinct function, and has been used throughout history with its own special meaning.

Umlaut is another interesting symbol, formed by placing two dots horizontally, usually in the margin preceding a 'doubtful' reading.

- two dots placed side by side, usually in margin.

- two dots placed side by side, usually in margin.

In the 4th and 5th century Uncials, the Umlaut appears to be the true and precise marker used to indicate a 'doubtful' reading retained in the text, and not the lemniscus. This ambiguity in the literature has caused some confusion and misunderstanding.

Metobelus is the 'end-marker' symbol. It looks something like a heavy colon in most Uncial MSS of the 4th to 7th centuries:

- two dots placed vertically at the end of a section.

- two dots placed vertically at the end of a section.

Although called a 'metobelus' ("end of an obelus"), it is in fact a general purpose end-marker, and paired off with a variety of critical symbols such as the asterisk and umlaut.

Early Textual Criticism:

The Dim Times

Lets look first at what the early textual critics said about marginal marks:

Davidson (1848): "The verses are marked with an obelus in S, and in about 30 (other) MSS. They are asterisked in E and in 14 (other) MSS. ...It is very remarkable too, that so many MSS having it, affix marks of rejection or interpolation."

(S. Davidson, Introduction to the NT, pg 356-357)

Tregelles (1854): "This narrative is found in some form or other in the following authorities: D F G H K U, and more than 300 cursive copies, without any note of doubt or distinction, as also in a few lectionaries.

In E it is marked with asterisks in the margin; so, too, in 16 cursive copies (two of which thus note only from viii. 3). In M there is an asterisk at vii. 53, and at viii. 3. In S, it is noted with obeli, and so, too, in more than 40 cursive codices."

(S.P. Tregelles, An Account of the Text of the Greek NT, pg 236f.)

Scrivener (1889): "The passage is noted by an asterisk or obelus or other mark in Codd. MS, 4, 8, 14, 18, 24, 34 (with an explanatory note), 35, 83, 109, 125, 141, 148 (secunda manu), 156, 161, 166, 167, 178, 179, 189, 196, 198,201, 202, 219, 226, 230, 231 (secunda manu), 241, 246, 271, 274, 277, 284 ?, 285, 338, 348, 360, 361, 363, 376, 391 (secunda manu), 394, 407, 408, 413 (a row of commas), 422, 436, 518 (secunda manu), 534, 542, 549, 568, 575, 600.

...Scholz, who has taken unusual pains in the examination of this question, enumerates 290 cursives, others since his time forty-one mre, which contain the paragraph with no trace of suspicion, as do the uncials D F (partly defective) G H K U G ..."

(F.H.A. Scrivener, A Plain Introduction... 4th Ed., pg 364f )

Hort (1896): " [ In support of omission: ]

(A) B (C) L T X, Delta, MSS known to Jerome, [cursives] 22 33 81 131 157 alpm, (besides many MSS which mark the section with asterisks or obeli )..."

(F.J.A. Hort, NT in the Original Greek, Appendix: Notes ... pg 83)

Lets now review some facts:

(1) The use of marginal marks in manuscripts spans 2,000 years.

(2) The marks come in a variety of forms, even on recent NT MSS.

(3) They supposedly only function to mark off doubtful passages.

All four of our early textual critics here imply that these marks indicate a doubtful passage, or a phrase that has been tagged as an interpolation. Even Mr. Scrivener, who is normally balanced and insightful, here seems to have followed the status quo.

Is this picture convincing, or even plausible? Sadly, no. It is highly unlikely that different kinds of markings would all have the same meaning. And its also unlikely that the usage and meaning of marginal marks would stay the same over such long time periods, and across many cultures and geographical regions.

Only Tregelles gives any hint that some markings might have other purposes. He says, "a note of doubt or distinction." And Tregelles is not simply conjecturing, as we shall see later. Honesty has compelled the critics to admit at least two different types of markings in the manuscripts, while the presentation itself misleads an unwary reader into thinking the marks are more or less similar.

Hort goes even further in the dubious way he presents this evidence. He groups ALL manuscripts with markings under the rubric of evidence *against* the authenticity of John 8:1-11. (Hort, Selected Notes, pg 83)

Is this really an "open and shut" case, or just another 'card-trick' in the debating game surrounding the Pericope de Adultera?

What can the real history of these markings tell us?

Plenty.

Asterisks and Obeli:

Categories of Usage

We can identify four categories of usage in the history of marginal markings:

(1) As they were originally used for ancient Greek plays and other literary works.

(2) As adopted for use in MSS of the Septuagint (LXX), the Greek Old Testament.

(3) As used in the old Uncials of the New Testament in the 4th and 5th centuries.

(4) As they were used in the later Byzantine MSS of the New Testament.

Asterisks and Obeli:

Classical Usage

Aristarchus of Samothrace (217-145 B.C.) A Greek critic and grammarian, noted for his contribution to Homeric studies. Aristarchus settled in Alexandria (170 B.C.?) where he was a pupil of Aristophanes of Byzantium, and around 153 B.C. became Aristophanes' successor as chief librarian there. Later he moved to Cyprus. He founded a school of philologists, called the Aristarcheans, which fourished for a long time in Alexandria and after that in Rome. He devoted his life to the elucidation and correct transmission of the text of the Greek poets, and especially Homer. Frequent quotations by ancient writers give insight into his method.

(sources: Encycl.Britt.Online, Nuttall Encycl., Columb. Elec. Encycl., )

It is not clear whether Aristarchus or his predecessor and teacher Aristophanes invented the original 'accents', or system of critical signs that Aristarchus used to correct and restore Homer's works. To correct the text, he marked with an obelus the lines he considered spurious; other signs were used by him to indicate comments, variant readings, accidental repetitions and interpolations.

"Our knowledge of Alexandrian criticism is derived almost wholly from a single document, the famous Iliad of the library of St Mark in Venice (Codex Venetus 454, or Ven. A), first published by the French scholar Villoison in 1788 (Scholia antiquissima ad Homeri Iliadem)." (from: http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Homer)

Venetus A: Aristarchus' practice is chiefly known from the 10th century MS Venetus A (codex Marcianus Graecus 454 in Venice). As well as the text of the Iliad, Venetus A preserves several layers of annotations, glosses, and comments known as the "A scholia". Although this manuscript is obviously 'late', the marginal critical marks are shown by ancient papyri fragments to reflect fairly accurately those that would have been in Aristarchus' edition of the Iliad.

The scholia in turn consist mainly of extracts from four scholarly works: that of Didymus, on Aristarchus' recension of Homer; Aristonicus (fl. 24 BCE) on Aristarchus' critical marks; Herodian (fl. 160 CE) on accents; and Nicanor (fl. 127 CE) on punctuation. For our inquiry, Aristonicus is the most important work.

We get a marvelous insight into the problem of establishing ancient usage of critical marks by consulting classical Greek scholarship. For instance, The following review provides a wealth of information on the state of opinion on this:

A Review of :

Martin L. West (ed.), Homerus Ilias volumen alterum, rhapsodiae XIII-XXIV."... The chapter on Alexandrian scholarship mixes well-documented observations with unwarranted speculations in a style filled with rhetorical questions, flourishes and asides. West begins with a general criticism of those scholars who viewed editorial work in Alexandria as the comparison of previous exemplars and the collecting of variant readings. and so cannot understand the true nature of the three Alexandrians' contributions, mainly those by Zenodotus. It is questionable whether West's mocking tone is justified; and his protest is, to my mind, both unnecessary and unfair since it takes the place of proper acknowledgement of scholarly debts. It deprives Marchinus van der Valk and Klaus Nickau of the merit of having provided us with a balanced account of Zenodotus and Aristarchus.

Unsurprisingly enough, the better part of what West holds here is a mere adaptation of Van der Valk's conclusions. 26 Zenodotus was arbitrary in his treatment of the text, he did not seek as if it were a rule earlier exemplars 27 but lavished his judgement on those which were at his disposal (non exemplaria contulit, non nouum exscripsit, uerum ueterem librum usurpauit q u e m h a b e b a t, p. VII) and he marked with the obelus every passage he deemed unworthy of his conception of 'Homer'. Such is the main core of his 'recension'; his textual ambitions were limited to a number of conjectures which found their way in Aristarchus' sets of notes. 28 Aristarchus, although he agreed with Aristophanes' more rational aims and methods (save that he produced two successive sets of notes keyed to his texts: ArA, ArB), was as arbitrary as Zenodotus in his singular readings, at least those that found no hospitality in the 'vulgate' (Van der Valk, Researches..., II, 90: "so far as Aristarchus' activities with regard to the Homeric text are concerned, we can say that he was no less prolific than Zenodotus in offering conjectures. Since, however, his emendations are less arbitrary, more scholarly and cautious, they have been less easily unmasked").

The risk of endorsing these views without qualification is patent: Van der Valk's conviction 29 that the Alexandrian critics were no less arbitrary in their establishing of the numerus uersuum 30 than they are in their constitutio textus, has not gone unchallenged. 31 West himself felt bound to accept the arguments for the validity of Aristarchus' criteria in establishing the number of verses deemed authentic in the text of the Homeric poems, as devised by Bolling, External Evidence..., and recast by M. J. Apthorp in a magisterial way (The Manuscript Evidence for Interpolation in Homer, Heidelberg, Winter, 1980). Actually, the reason West partially endorses Van der Valk in the field of constitutio textus may well be that he himself has a revolutionary theory to offer: contrary to the evidence of the A scholia, the quotations of textual criticism by Didymus do not show any first-hand collation of earlier exemplars by Aristarchus, whose riches Didymus was able to extract from different versions of the Aristarchean notes he had access to. No one besides Didymus sought variant readings; he collated as much textual evidence as was accessible to him, in an unsystematic way. To him should therefore be assigned the whole body of evidence relevant to the pre-Alexandrian state of the text. No more than Gregory Nagy in his review of West's vol. 1 (BMCR 00.09.12) am I able to agree with this theory. 32 That Didymus nouit the thousands of readings he is credited with remains mere speculation. It would have been had West first given his proofs in a separate paper or monograph. It is unfortunate that he has weighted with his authority and the one of a Teubner edition such a highly debatable novelty."

(Jean-Fabrice Nardelli, Université de Provence, A Review of :

Martin L. West (ed.), Homerus Ilias volumen alterum, rhapsodiae XIII-XXIV.

Munich/Leipzig: K.G. Saur, 2000. Pp. viii, 396. ISBN 3-598-71435-1. DM 69.00 (pb).

(jean-fabrice.nardelli@wanadoo.fr)

http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/bmcr/2001/2001-06-21.html#n28

Footnotes:

26. Researches on The Text and Scholia of the Iliad, II, Leiden..., Brill, 1964, 1-83 (Zenodotus) and 84-263 (Aristarchus). These studies had been called, with some reason, "astute if sometimes arcane" by G. S. Kirk, The Iliad. A Commentary, I, Cambridge, C.U.P., 1985, 43. See note 29.

27. This seems to be directed against two contentions of Bolling, Athetized Lines..., 32-33:

First, "Zenodotus' chief problem was the problem of the lines. He solved it I believe not eclectically (so Wolf and many others), but by deciding to include in his text the lines upon which his manuscripts agreed; and also--but with a mark (obelus) in front of them--a selection from the lines about which the testimony of his manuscripts fluctuated" (p. 32, last paragraph).

Secondly, "What then did Zenodotus' obelus mean?...For his obeli I can find no reasonable meaning except 'Here the tradition is not a unit'. At least such must have been their primary meaning. For in the absence of a commentary it must have been something true of all marked passages, something that could be stated once for all; and--the only alternative--a meaning 'These verses are to be judged spurious for various unstated reasons' would have offered to his readers nothing but a series of placita" (p. 33).

28. My use of hupomnêma (and my translation of it) are explained in Éditer l'Iliade I, note 132.

29. This is made explicit by Pfeiffer in the Addenda to his History of Classical Scholarship..., I, 287: "...his opinion that 'the Alexandrian critics had no correct idea of the significance of a diplomatic text', which is now openly expressed (pp. 565 ff.), was the unspoken assumption behind his Textual Criticism of the Odyssey (1949) and the first volume of his Researches on the Text and Scholia of the Iliad (1963), and must unfortunately be regarded as a preconceived idea, not the result of historical inquiries". A similar observation was implicit as soon as 1950 in Bolling's presentation of the Alexandrian's methods (AJPh. 71, 306-311). See note 30 below and my Éditer l'Iliade, note 133.

30. Researches..., II, 370-477 ("Atheteses of Aristarchus") and 477-530 ("so-called Additional Lines"). These chapters are rashly, but not unfairly, assessed by Apthorp, Manuscript Evidence..., XV when he goes on to explain that Van der Valk refused to accept that the evidence put forward by Ludwich and Bolling, External Evidence... "shows conclusively that

omitted only lines which were absent in the vast majority of his manuscripts". Such a negation of the case which can be made in favor of Aristarchus' conservatism in this area stems from the ardent oralist faith of the Dutch critic. In this precise sense his book is misleading. 31. Antonios Rengakos, Der Homertext und die hellenistischen Dichter, "Hermes Einzelschriften" 64, Stuttgart, Steiner, 1993, argues at some length (197 pages) for systematically validating the editorial standards of the Alexandrians. His position holds good on a few points of detail, generally referred to in West's apparatus, but the uncertainty of such an approach remains a major deterrent (it can fairly be said that it does little more than make a system out of Erbse's demonstration of Apollonius Rhodius' incontrovertible dependence on Homeric scholarship: "Homerscholien und hellenistische Glossare bei Apollonios Rhodios", Hermes 81 [1953], 163-196). This wild element of speculation is compounded by the somewhat too large focus of Rengakos' approach (it applies to Zenodotus and Aristophanes as well as Aristarchus, and to their choice of variant readings no less than to their counting of the lines).

32. I am sanguine enough to consider that, given the evidence both external and internal, the reasons for my skepticism (Éditer l'Iliade I, 8 and 28) and Nagy's will not be easily refuted. The systematic device of the apparatus "nou(it) Did(ymum)", being undocumented, throws no light at all on the transmission and deprives Aristarchus of one of his main merits. Now, if really he did not use manuscripts as the basis of his recensions, why on earth did he undertake his successive sets of notes explaining his texts and why did he produce polemical treatises on particular points? Such a reductio ad absurdum is probably mere surmise, but I cannot help suspecting that West has been led astray by the anti-Aristarchean current prejudice, of which Van der Valk and Hartmut Erbse are the main supporters. The burden of the proof lies with him. Finally, for Didymus as a collator, Nagy argues a not unimportant point: "this is not to say that Didymus did not collate Homer manuscripts in his own right or that Aristarchus was the only collator...It is only to say that the primary collator of Homer manuscripts was Aristarchus himself and that Didymus may not have had access to all the sources still available to Aristarchus" (his note 21).

There is quite a remarkable amount of controversy smoking below the scholarly surface here, and we cannot enter into those disputes. But several less controversial facts seem plausible and agreed upon by classical scholars:

(1) The Obelus is the only symbol indesputably used for 'doubtful' passages. We can find no support for such an interpretation of other signs, such as the Asterisk.

(2) Even here the Obelus appears to have been used, not to mark a specific reading as spurious, but simply to indicate that a section of the text varied between copies...

And the reader therefore is simply warned that the reading adopted might not necessarily be the right one. This insight by Bolling is enlightening and difficult to resist.

The corollary is that in spite of a known variation, presumably the 'best guess' is the reading actually included in the manuscript normally. Of all variant readings, this would NOT be the one most suspect, unless the marks were added by a second hand, after the copy was made.

In any case, an alternate less positive view of the reading found would seem to hinge NOT upon the question of the mere existance of marginal marks, but upon their being by a second hand or subsequent corrective activity.

Asterisks and Obeli:

Usage in the LXX

Origen of Alexandria (c 240 A.D.)

The first to systematically apply the critical marks of the Alexandrian critics was Origen.

"In the Septuagint column [Origen] used the system of diacritical marks which was in use with the Alexandrian critics of Homer, especially Aristarchus, marking with an obelus under different forms, as

, called lemniscus, and

, called a hypolemniscus, those passages of the Septuagint which had nothing to correspond to in Hebrew, and inserting, chiefly from Theodotion under an asterisk (

), those which were missing in the Septuagint; in both cases a metobelus (

) marked the end of the notation."

(Schaff-Herzog Encycl. of Religious Knowl. Vol II: Bascilica - Chambers, I. Greek Vers. 1. LXX, ~ 4, Hexapla of Origen,

http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/encyc02.bible_versions.html )

Note: Schaff is the only source we know for the actual use of the lemniscus / hypolemniscus as an obelus in function. Though he probably bases this upon real MSS, we would like to see some specific examples of both the symbols and unambiguous cases of their function. He also gives the metobelus as a 'gamma' symbol, rather than a colon.

Yet Schaff also seems to confuse the issue of what Origen himself used, and what copyists later substituted for the 'obelus' symbol and function. Alternately, Schaff may be implying that Origen used multiple symbols for the same function: but if Origen actually used several distinct symbols, then it is unlikely that they had the exact same meaning. More probable, is that here again some critics, possibly following copyists, may have oversimplified what Origen actually did.

The method which Origen adopted is described by himself in his famous letter to Africanus (c. A.D. 240), and more fully in his commentary on St Matthew (c. A.D. 245).

The Letter to Africanus:

3. And in many other of the sacred books I found sometimes more in our copies than in the Hebrew, sometimes less. I shall adduce a few examples, since it is impossible to give them all. ...

4. ...which I marked, for the sake of distinction, with the sign the Greeks call an obelis, as on the other hand I marked with an asterisk those passages in our copies which are not found in the Hebrew.

... And, what, when we notice such things, we are now to reject as spurious the copies in use in our Churches, and ask the brotherhood to put away the Holy Scriptures current among them, and to go begging to the Jews, and persuade them to give us 'untampered' copies, and free from forgery!?!

Are we really to suppose that that Providence which in the sacred Scriptures has ministered to the edification of all the Churches of Christ, had no thought for those bought with a price, for whom Christ died; whom, although His Son, God who is love spared not, but gave Him up for us all, that with Him He might freely give us all things?

5. In all these cases [of dispute] consider that it is well to remember the words, "Thou shalt not remove the ancient landmarks which thy fathers have set." [Prov.22:28, cf.Deut.19:14]

Nor do I say this because I shun the labour of investigating the Jewish (Hebrew) Scriptures, comparing them with ours (the Greek text), to note their variant readings. This, if it isn't boasting to mention it, I have already to a great extent done this to the best of my ability, working hard to get at the meaning in all the editions and variant readings:

And I paid particular attention to the interpretation of the LXX (Greek OT), rather than be found to attribute any forgery to the Churches under heaven, or give opportunity to those seeking such a start to fulfill their wish to slander our common brothers, and bring some accusation against those who enlighten our community.

And I make it my business to be aware of variant readings, in case in my debates with the Jews I were to quote something not found in their (Hebrew) copies. - And also so that I can make some use of what is found there (in the Hebrew text), even though it isnt in our (Greek) Scriptures. For if we are prepared this way in our discussions, they won't in their usual manner mock Gentile believers for their ignorance of the 'true reading' as they have them.

ad Afric. 5: " kai tauta de fhmi ouci oknw tou ereunan kai taV kata IoudaiouV grafaV kai pasaV taV hmeteraV taiV ekeinwn sugkrinein kai oran taV autaiV diaforaV, ei mh fortikon goun eipein, epi polu touto osh dunamiV pepoihkamen, gumnazonteV autwn ton noun en pasaiV taiV ekdosesi kai taiV diaforaiV autwn meta tou poswV mallon askein thn ermhneian twn ebdomhkonta...askoumen de mh agnoein kai taV par ekeinoiV, ina proV IoudaiouV dialogomenoi mh prosferwmen autoiV ta mh keimena en toiV antigrafoiV autwn, kai ina sugcrhswmeqa toiV feromenoiV par ekeinoiV, ei kai en toiV hmeteroiV ou keitai biblioiV. "

9. But probably to this you will say, Why then is the "History" not in their Daniel, if, as you say, their wise men hand down by tradition such stories? The answer is, that they hid from the knowledge of the people as many of the passages which contained any scandal against the elders, rulers, and judges, as they could, some of which have been preserved in uncanonical writings (Apocrypha).

As an example, take the story told about Isaiah; and guaranteed by the Epistle to the Hebrews, which is found in none of their public (Hebrew OT) books. For the author of the Epistle to the Hebrews, in speaking of the prophets, and what they suffered, says, "They were stoned, they were sawn asunder, they were slain with the sword"

To whom, I ask, does the "sawn asunder" refer (for by an old idiom, not peculiar to Hebrew, but found also in Greek, this is said in the plural, although it refers to but one person)?

Now we know very well that tradition says that Isaiah the prophet was sawn asunder; and this is found in some apocryphal work, which probably the Judaeans have purposely tampered with, introducing some phrases manifestly incorrect, that discredit might be thrown on the whole."

(cf. http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/origen-africanus2.html)

Commentary on Matthew:

"By the gift of God we found a remedy for the divergence in the copies of the Old Testament, namely to use the other editions as a criterion" (Commentary on Matthew 15:14).

in Matt. 15:14: " thn men oun en toiV antigrafoiV thV palaiaV diaqhkhV diafwnian, qeou didontoV, euromen iasasqai, krithriw crhsamenoi taiV loipaiV ekdosesin twn gar amfiballomenwn para toiV o dia thn twn antigrafwn diafwnian, thn krisin poihsamenoi apo twn loipwn ekdosewn, to sunadon ekeinaiV efulaxamen: kai tina men wbelisamen en tw Ebraikw mhn keimena, ou tolmwnteV auta panth perielein, tina de met asteriskwn proseqhkamen: ina dhlon h oti mh keimena para toiV o ek twn loipwn ekdosewn sumfwnwV tw Ebraikw proseqhkamen, kai o men boulomenoV prohtai auta w de proskoptei to toiouton, o bouletai peri thV paradochV autwn h mh poihsh. "

(We have had difficulty locating Swete's source for the above section. Most published editions of Origen stop at Book 14...)

Book X, Chapter 22: para.22 "...And note, further, that not openly but secretly and in prison does Herod put John to death. - For even the present (Hebrew) scripture of the Judaeans does not openly deny the prophecies, but virtually and in secret denies them, and is convicted of disbelieving them.

For as "if they believed Moses they would have believed Jesus,"

so if they had believed the prophets they would have received Him who was the subject of prophecy. But disbelieving Him they also disbelieve them (the scriptures), and cut off and imprison the prophetic word and keep it dead and divided, and in no way wholesome, since they do not understand it. But we have the whole Jesus, with the prophecy about Him fulfilled which says,

'A bone shall not be broken.'(cf. http://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/ecf/009/0090373.htm)

From comments like these, it is pretty clear that Origen certainly did not intend to actually correct the LXX (Christian OT) using the contemporary Hebrew texts used by the Jews. Rather, his intent was to educate other Christians about those differences, and equip them for debate.

In his own view, passages missing in the Hebrew were likely deleted by Jews on purpose. He doesn't take quite the same view of passages missing in the Greek, although he is quite happy to treat such additions as spurious if necessary. He supplies the Greek counterpart to these from Jewish translations of the OT.

In both cases, it is quite clear that Origen does not at all have in mind the suggestion that the LXX readings, or even the Hebrew readings are 'spurious'. Origen's respect for the Greek text is plainly supreme, and he has merely adopted the critical marks to his own quite different and diverse purposes. He has not really intended we take their original meaning at all, nor would he be constrained by that.

In this usage of 'critical marks' like the obelus and asterisk, it seems quite clear that the Greek church for the most part followed Origen, and not the classical Alexandrian editors. To this day, the Eastern Orthodox church has resisted the wholesale correcting of the Greek text by reference to the (Massoretic) Hebrew text.

Critical Scholarship and the Septuagint

Swete provides a scholarly view and some corroborating evidence on Origen. Yet Swete's account twists and turns strangely, in anticipation of Swete's own spin on Origen:

Swete's Introduction to the LXX: Chapt III:

"1. ...(Origen) was impressed with the importance of providing the Church with materials for ascertaining the true text and meaning of the original." 1 ...

Swete then quotes some of the above exerpts by Origen (To Africanus, and Comm. on Matt.), in Greek. He continues:

"2. To attempt a new version was impracticable. It may be doubted whether Origen possessed the requisite knowledge of Hebrew; 2 it is certain that he would have regarded the task as almost impious. Writing to Africanus he defends the apocryphal additions to Daniel and other Septuagintal departures from the Hebrew text on the ground that the Alexandrian Bible 3 had received the sanction of the Church, and that to reject its testimony would be to revolutionise her canon of the Old Testament, and to play into the hands of her Jewish adversaries:" (here Swete quotes To Africanus again in Greek).

In this matter it was well, he urged, to bear in mind the precept of Prov. 22:28 (see above). The same reasons prevented him from adopting any of the other versions in place of the Septuagint.

On the other hand, Origen held that Christians must be taught frankly to recognise the divergences between the LXX and the current Hebrew text, and the superiority of Aquila and the other, later versions, in so far as they were more faithful to the original; 4

It was unfair to the Jew to quote against him passages from the LXX which were wanting in his own Bible, and injurious to the Church herself to withhold from her anything in the Hebrew Bible which the LXX did not represent. 5 ... (Here follows some sample columns of the Hexapla.)

...The process as a whole is minutely described by Eusebius and Jerome, who had seen the work, and by Epiphanius, whose account is still more explicit but less trustworthy. 6 (here Swete quotes Eusebius in Greek, Jerome in Latin, and Epiphanius in Greek again.)

3. ...With regard to the order, it is clear that Origen did not mean it to be chronological. Epiphanius seeks to account for the position of the LXX in the fifth column by the not less untenable hypothesis that Origen regarded the LXX as the standard of accuracy: 7 (Epiphanius, again in Greek)

As we have learned from Origen himself, the fact was the reverse; the other Greek versions were intended to check and correct the LXX. 8 But the remark, though futile in itself, suggests a probable explanation:

Aquila is placed next to the Hebrew text because his translation is the most verbally exact, and Symmachus and Theodotion follow Aquila and the LXX. respectively, because Symmachus on the whole is a revision of Aquila, and Theodotion of the LXX. ...

5. ... every column of the Greek contained clauses which were not in the Hebrew, and omitted clauses which the Hebrew contained. Further, in many places the order of the Greek would be found to depart from that of the Hebrew ... Lastly, in innumerable places the LXX would be seen to yield a sense more or less at variance with the current Hebrew...These causes combined to render the coordination of the Alexandrian Greek with the existing Hebrew text a task of no ordinary difficulty...

Origen began by assuming (1) the purity of the Hebrew text, and (2) the corruption of the Koine where it departed from the Hebrew 9 (See Driver, Samuel , p. xlvi.: "he assumed that the original Septuagint was that which agreed most closely with the Hebrew text as he knew it . . . a step in the wrong direction.") .

The problem before him was to restore the LXX. to its original purity, i.e. to the Hebraica veritas as he understood it, and thus to put the Church in possession of an adequate Greek version of the O.T. without disturbing its general allegiance to the time-honoured work of the Alexandrian translators. 10

Swete's great work is immense, and can hardly be ignored by Septuagint researchers. However, it suffers from some systemic distortions. We can't begin an exhaustive critique of Swete here, but we can note some unscientific blemishes that lead to an 'interpretation' of Origen that somewhat strains the historical facts.

1. Swete here projects an anachronistic viewpoint upon Origen that reflects the attitude of modern textual critics, but would have been foreign to Origen's world view and thinking processes, as reflected in his own copious writing. Origen firmly believed in the superiority and essential accuracy of the Greek OT (LXX), and was one of the first fathers to articulate a clear and sophisticated expression of the doctrine of Divine Preservation. For Origen this doctrine took for granted that the Christians had the 'true' text, and the Jews had mutilated theirs.

2. Swete inexplicably slams Origen's Hebrew skills. Other writers ancient and modern could only praise his phenomenal linguistic achievements. This is again a strange way of explaining the obvious: Origen was too humble a Christian, or at least had too much common sense to try making a translation to compete with the LXX. Part of the problem was that there were too many translations already, and yet another would just add confusion. He was more concerned with textual matters.

3. Again Swete uses loaded expressions. Strictly speaking it wasn't the 'Alexandrian Bible' that had the approval of Christians, but the Greek O.T. The NT was a completely different case, and originated elsewhere. Nor was Origen this modern and sophisticated in his thinking. He was certainly concerned that Christians might be mocked if unprepared for debate with Jews, but his 'ground' wasn't logical considerations of 'revolutionizing the canon' or 'playing into enemy hands'. His 'ground' was that he believed the pure OT (LXX) and NT had been delivered already into the hands of the Apostles and the Church.

4. The agenda of a modern textual critic is again projected onto Origen. But everything Origen actually said paints an entirely different picture. The anachronism and the corollary, the necessity of charging Origen with a kind of 'pious duplicity' is implausible in the light of Origen's continuous and uniform speech to the contrary. Nothing in Origen's letter to Africanus for instance can be taken to mean anything other than that Origen believed in the essential truth and accuracy of the LXX, already held by the Church.

5. If Origen had any covert agenda at all, it certainly wasn't to 'rescue true Hebrew' variant readings for the Church. Origen rather suggests that the Hebrew variants might have a 'use' in debates with the Jews. But this rather sinister hint of an unspecified use hardly reflects a high view of the Hebrew text. Rather, if his copious remarks about Jewish fraud and forgery are any indication at all of his true beliefs, its this that colors his outlook on the Hebrew.

6. Now Swete sets up Epiphanius for some slagging. And the reason will become immediately apparent.

7. Now the target is revealed: Swete wants to discount Epiphanius' testimony as to Origen's high view of the LXX. Swete wants to present Origen instead as the cagey textual critic who wants to bring in readings from the 'original' Hebrew. At the time of Swete's writing, Protestants the world over had opted to embrace the Hebrew Massoretic text over the traditional Greek OT used by Christians for a thousand years. They were eager to present ancients like Origen as holding the same views, no matter how anachronistic the inconvenient facts make this appear.

8. Unfortunately, we haven't learned anything like Swete's assertion here from Origen. On the contrary, the Letter to Africanus stands in direct opposition to Swete's thesis. Presenting the difficult texts in Greek may prevent most from investigating Swete's claims more closely, but we can only find the ruse annoying.

9. Origen's assumptions are wholly unkown. He certainly acquired a familiarity with the textual variants in the process of his work. Swete cites Driver, but Driver doesn't really support Swete's contention at all. Later, in writing to Africanus, either Origen was engaging in an incredibly elaborate lie, or long after producing his work he remained convinced that the LXX was the pure text, and it was the Hebrew was corrupt. The latter option is the only one supported by any historical evidence.

10. Once again the anachronistic and totally foreign view of the modern textual critic is projected back upon the ancient apologist, and couched in the especially implausible terms of a liberal academic.

Knowing the artificial coloring of Swete's work at least prepares us to appreciate the more valuable data he provides, and evaluate his necessary admissions more accurately:

Swete's Introduction: Chapt III: (cont.)

Some of the elements in this complex process were comparatively simple. (1) Differences of order were met by transposition, the Greek order making way for the Hebrew. In this manner whole sections changed places...[but] in Proverbs only, for some reason not easy to determine, the two texts were allowed to follow their respective courses, 11 and the divergence...was indicated by certain marks (A combination of the asterisk and obelus; see below) prefixed to the stichi (lines of text)...

(2) Corruptions in the Koine, real or supposed, were tacitly corrected in the Hexapla, whether from better MSS of the LXX, or from the renderings of other translators, or, in the case of proper names, by a simple adaptation of the Alexandrian Greek form to that which was found in the current Hebrew. (Whether his practice in this respect was uniform has not been definitely ascertained.) 12

(3) The additions and omissions in the LXX. presented greater difficulty. Origen was unwilling to remove the former, for they belonged to the version which the Church had sanctioned, and which many Christians regarded as inspired Scripture; but he was equally unwilling to leave them without some mark of editorial disapprobation. 13 Omissions were readily supplied from one of the other versions, namely Aquila or Theodotion; but the new matter interpolated into the LXX. needed to be carefully distinguished from the genuine work of the Alexandrian translators.

6. Here the genius of Origen found an ally in the system of critical signs which had its origin among the older scholars of Alexandria, dating almost from the century which produced the earlier books of the LXX. The [Aristarchian Signs] took their name from the prince of Alexandrian grammarians, Aristarchus, who flourished in the reign of Philopator (A.D. 222-205) [sic! Read 222-205 B.C. here!]

...Origen selected two of these signs known as the obelus 14 and the asterisk, and adapted them to the use of his edition of the Septuagint. In the Homeric poems, as edited by Aristarchus, the obelus marked passages which the critic wished to censure, while the asterisk was affixed to those which seemed to him to be worthy of special attention.

As employed by Origen in the fifth column of the Hexapla, the obelus was prefixed to words or lines which were wanting in the Hebrew, and therefore, from Origen's point of view, of doubtful authority 15 (On an exceptional case in which he obelised words which stood in the Hebrew text, see Cornill, Ezechiel , p. 386 (on xxxii. 17). ,

- whilst the asterisk called attention to words or lines wanting in the LXX., but present in the Hebrew. The close of the context to which the obelus or asterisk was intended to apply was marked by another sign known as the metobelus. 16 When the passage exceeded the length of a single line, the asterisk or obelus was repeated at the beginning of each subsequent line until the metobelus was reached.

Other Uses of the Same Signs:

Occasionally Origen used asterisk and obelus together, as Aristarchus had done, to denote that the order of the Greek was at fault 17 ...

The Aristarchian (or ... Hexaplaric) signs are also used by Origen when he attempts to place before the reader of his LXX column an exact version of the Hebrew without displacing the LXX rendering. 18

Where the LXX. and the current Hebrew are hopelessly at issue, he occasionally gives two versions, that of one of the later translators distinguished by an asterisk, and that of the LXX. under an obelus 19

{A somewhat different view of Origen's practice is suggested by H. Lietzmann ( Gott. gel. Anz. 1902, 5) and G. Mercati ( Atti d. R. Acc. d. Sci. di Torino , 10 Apr. 1896: vol. 31, p. 656 ff.}

The form of the asterisk, obelus, and metobelus varies slightly. The first consists of the letter X, usually surrounded by four dots (

, the ci teriestigmenon ); the form

occurs but seldom, and only, as it seems, in the Syro-Hexaplar. The obeloV , 'spit' or 'spear,' is represented in Epiphanius by

, but in the MSS. of the LXX. a horizontal straight line (

) {This sometimes becomes a hook

} has taken the place of the original form, with or without occupying dot or dots (

); the form

was known as a lemniscus, and the form

as a hypolemniscus.

(Epiphanius indeed (op. cit., c. 8) fancies that each dot represents a pair of translators, so that the lemniscus means that the word or clause which the LXX. adds to the Hebrew had the support of two out of the thirty-six pairs which composed the whole body, whilst the hypolemniscus claims for it the support of only one pair. This explanation, it is scarcely necessary to say, is as baseless as the fiction of the cells on which, in the later Epiphanian form, it rests.) 20

Other attempts to assign distinct values to the various forms of the obelus have been shewn by Field to be untenable {Prolegg. p. lix. sq. }. 21 The metobelus is usually represented by two dots arranged perpendicularly (

), like a colon; other forms are a sloping line with a dot before it or on either side (

,

), and in the Syro-Hexaplar and other Syriac versions a mallet

. 22

11. Swete's interpretation of Origen's work is hardly out of the starting-gate, and runs into some snags. We see Origen departing from the 'plan', and using the same symbols in novel combinations to indicate new technical variants, namely section-order. Nothing is simple, when your explanation won't line up with important facts.

12. This is unremarkable, and hardly supports Swete's assertion that Origen wanted to revise the LXX according to the Hebrew text. These minor corrections by secondary MSS, or adoptions of spelling conventions are business as usual inside any scriptorium.

13. Again, the twist is ironic: Its not that "many (other) Christians regarded the LXX text as inspired Scripture - its that Origen himself regarded it as inspired scripture. Swete tries to transfer the obvious attitude of Origen onto the Church, or other 'ignorant' Christians, but its Origen who has all the attitude. He just isn't the modern textual critic that everyone wants to make him into, and can't be.

14. The systemic error here is the confusion of function (the obelus) with form. Origen adopted two symbols for his purposes, already familiar to scribes. But each acquired new functions and meaning under his hand. All Origen really required was two easily distinguishable symbols. Any pair of such symbols would have served equally well.

15. Here again Swete insists on the sales pitch, instead of just keeping to the facts. It constant repetition of his thesis begins to sound doubtful, if not hysterical.

16. Technically, the name 'metobelus' is also a misnomer, confusing association with multiple functions. Like a period at the end of sentence, it is lexically empty. But this confusing name was a convention long before Origen, and Swete can hardly be faulted for its perpetuation. Since in this case the effect of the flaw is nil, insisting upon a new name for the symbol, like 'generic closer-mark' would be nitpicking.

17. That is, Origen adopts another convention for his specialist purposes.

18. In other words, an 'insertion' of explanatory material. Now we have two new meanings, and Origen hasn't used more than two symbols so far!

19. Now Origen uses an 'obelus' to denote the LXX, using two parallel columns, with the non-LXX marked by an asterisk. But Swete doesn't dare suggest the 'obelus' means 'doubtful' or 'for excision' now: For why would Origen go to the extra trouble to present two separate columns, if he meant the LXX was the 'wrong' reading? Swete footnotes Lietzmann's interpretation of Origen in silence. He is compelled to acknowledge alternatives to his own version of events, which seems to have completely unravelled at this point.

20. In this case, Swete probably has a case. Epiphanius' explanations appear naive, and more importantly, unsubstantiated. Yet here again is plain evidence of another kind: testimony that various signs are believed to have various meanings. Its hard to deny some truth to this, in light of the various uses that Swete himself has documented.

21. Apparently Swete is unaware of the impact of Field's findings upon his own position. Obviously the multiplicity and instability of meanings for the various signs as used by Christians does little to solidify the thesis that Origen intended to 'cast doubt' upon LXX readings.

22. Finally, Swete gives us the goods in this section: useful and detailed information about the various signs. We can't help asking however, if Swete's epithet for Epiphanius doesn't apply to himself here: "...his account is still more explicit, ...but less trustworthy."

Summary on Swete: (cont.)

Swete offers plenty of evidence for a variety of uses of the various critical signs, as used by Christians in the LXX manuscripts. But there seems to be a strange lack of evidence regarding Origen's original purpose, and the way Christians subsequently understood Origen, and how they later used the symbols themselves.

Uncial MSS of the Septuagint

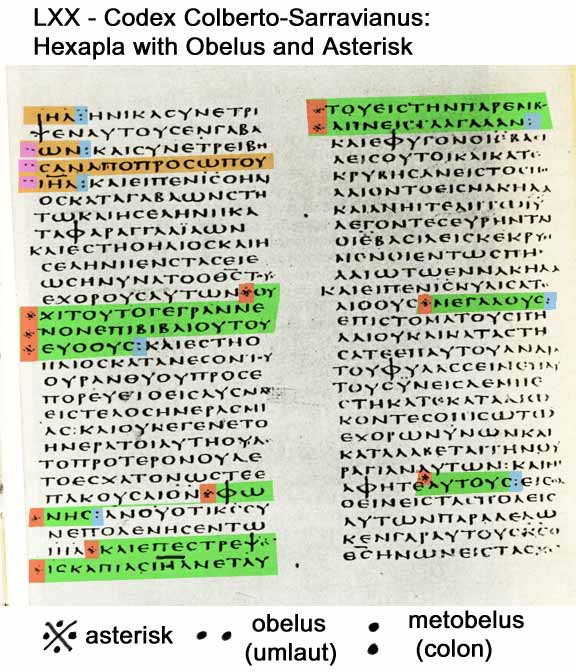

This manuscript is an excellent example of how these critical markings were typically used in UNCIAL manuscripts of the 4th and 5th centuries (A.D.), for the Old Testament (LXX) portion.

The Hexapla

The markings in question are collectively called the markings of the 'Hexapla', a special six-column master-manuscript made by Origen through comparing the Hebrew and the various independant Greek translations available in the early 3rd century.

This example was taken from the appendix of The Text of the Old Testament by Wurthwein (Eng.xlation). Although his description of this page has flaws, his basic explanation is sound:

"On the page shown an obelos [sic] marks the words: This indicates that Origen found these words in the LXX, but that they were NOT in the Hebrew text.

Several passages in the illustration are marked with an asterisk; this indicates that Origen did not find them in the LXX, and supplied them from other Greek versions (typically Theodotus).

When such a passage extends over several lines, the Aristarchan sign is repeated before each line; cf. for example v.15 which is lacking in LXX and is given here with an asterisk (lower left to upper right column). " (p 190)

What is of particular interest here however, is the actual form of the 'obelus'. It is in fact an umlaut. There is no doubt in this case that the function is indeed that of 'obelus', at least according to Origen's version of that function.

Here the 'obelus' (actually an umlaut, a sideways colon) marks a part of the Greek which is not found in the 2nd century A.D. (Massoretic) Hebrew text.

The 'Asterisk' is used also by Origen (and copied here), to indicate a favoured or 'restored' passage either translated freshly into Greek from Hebrew or borrowed from another independant translation, like Theodotus and supported by the Hebrew.

In each case, the END of the passage is marked by a 'metobelus', in this manuscript a simple 'colon'..

When the passage extends beyond a single line, each new line that continues the reading is marked also at the beginning (outside the margin) with the same sign (either Asterisk or Obelus).

The most important thing about this particular example here, is that we can observe that these marks are indeed by the original scribe, since in many cases, the beginning and ending marks are actually IN THE MAIN TEXT. The text has not been erased and re-written to make room. Instead, obviously the original scribe was aware of the Hexapla markings and incorporated them into his text as he wrote.

Occasionally the scribe misses inserting a mark, as in the very last example on the page. Note even here he does not erase even a small group of letters, but inserts the mark above the line and continues, probably doing this also in the process of writing the main text.

This key observation is critically important, because when we come to examine NEW TESTAMENT portions of uncial manuscripts, like Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, this is NOT the case! In the NT, these marks are clearly added later in a 'second pass' over the text by an 'annotator'.

So we have a case again of a different symbol, this time the umlaut, actually performing the function of 'obelus'. Yet we still lack a case of the lemniscus doing this duty.

Jerome (392 A.D.) on the Asterisk and Obelus: His own usage

"...In the text you will come across either a horizontal stroke ( ) or a "star" sign (

) or a "star" sign ( ), that is, either an obelus or an asterisk.

), that is, either an obelus or an asterisk.

And wherever you see the first "stroke" ( ) 2, beginning from there to the two dots (

) 2, beginning from there to the two dots ( ) 4 which we have marked in, you then know that this surplus text was found in the LXX (Greek OT) [but not in the Hebrew text].

) 4 which we have marked in, you then know that this surplus text was found in the LXX (Greek OT) [but not in the Hebrew text].

And where you see the "star" symbol ( ), 3 you'll know its an addition taken instead from the Hebrew, [but this time not found in the LXX], again up to the two dots (

), 3 you'll know its an addition taken instead from the Hebrew, [but this time not found in the LXX], again up to the two dots ( ). 4 Only here I've used Theodotion's translation, as its in the same style as the LXX."

). 4 Only here I've used Theodotion's translation, as its in the same style as the LXX."

(Jerome, Preface to the Latin Psalter )

1. meaning the obelus, a "sideways" mark with two dots:

"  "

"

2. The "stroke" is the obelus, "  "

"

3 Jerome's asterisk mark was "  "

"

4 Placed vertically, like our colon, and called a metobelus - "  "

"

Asterisks and Obeli:

Usage in the NT Uncials

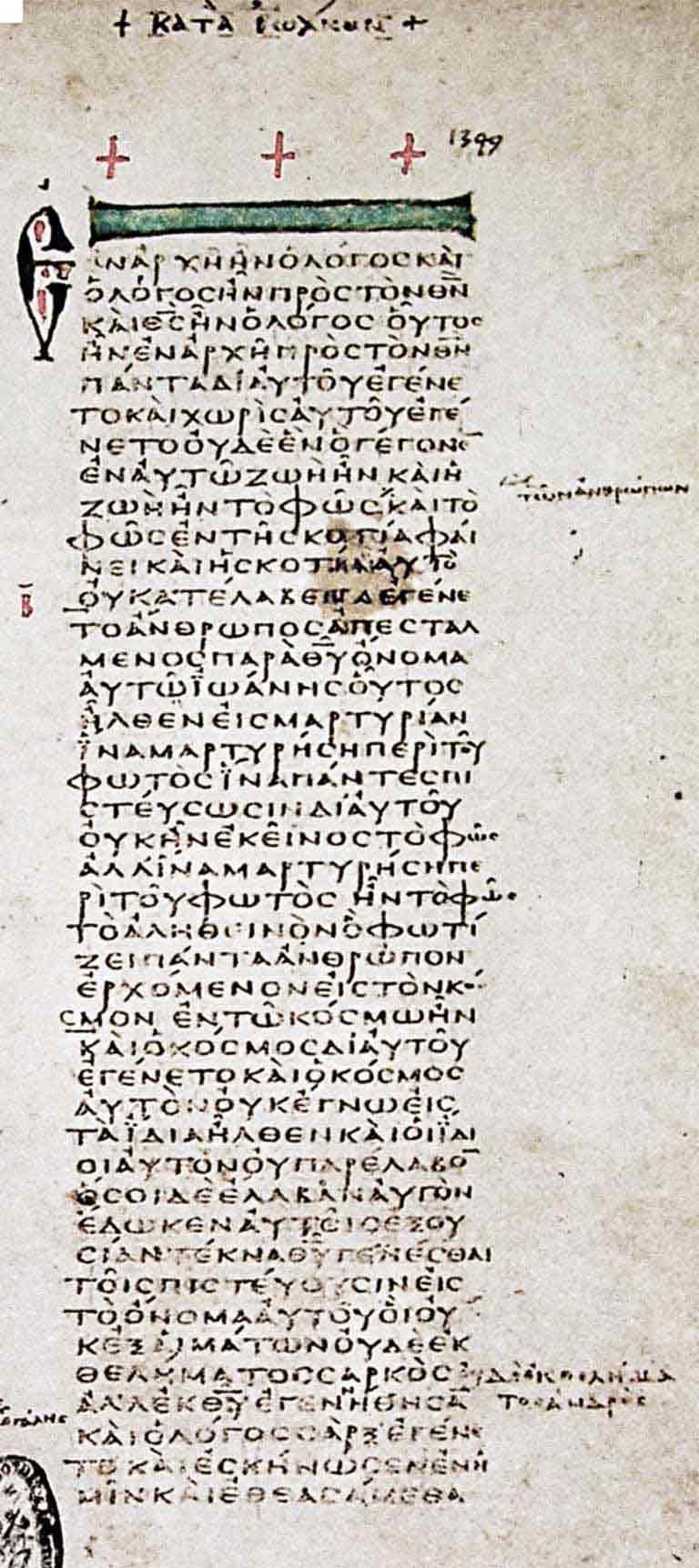

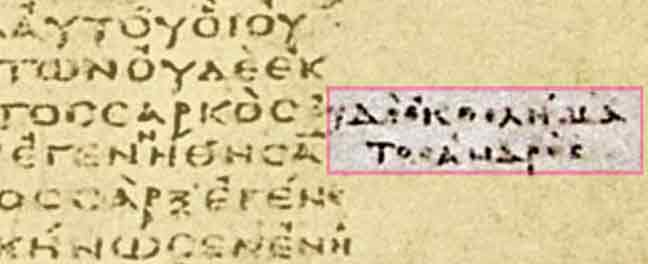

There are plenty of examples of NT usage in the old Uncials. For instance, here are two cases in the very first column of the Gospel of John from Codex Vaticanus:

The first thing to note is that these markings are NOT included in the text. The original copy-work appears oblivious to these notes or 'corrections'. They were in no way incorporated into the text during the 'first pass' or while the manuscript was being first written.

Instead, they are obviously added later, often with what is called a lemniscus ( ) marking the point in the text, (usually squeezed into the space between the lines), and the missing text to be inserted in the right margin.

) marking the point in the text, (usually squeezed into the space between the lines), and the missing text to be inserted in the right margin.

Again, observation makes it equally clear that the corrections are later additions, just the opposite of the previous case (Codex Colberto) where it was obvious that the scribe had included the notes on the fly and incorporated them right into the main text of the LXX.

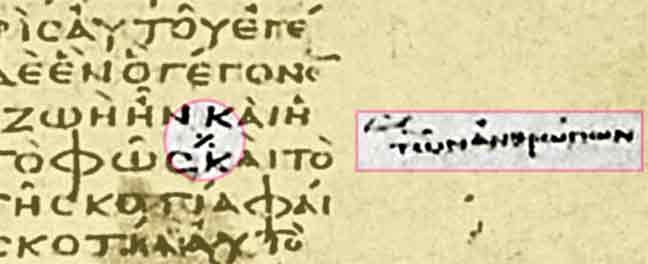

Case 1: Line 9

In this specific case, a 2nd hand has corrected line 9, where the original scribe has dropped the phrase "of men" (twn anqrwpwn) from the text, making a nonsensical reading. Obviously, the original scribe blundered, and the corrector is 'correct' in adding a note for later copyists to insert the phrase back in.

This can in no way be interpreted as an attempted 'scribal gloss' or addition to an original text. These manuscripts are 4 centuries away from the original autographs, and are products of sophisticated professional scriptoriums. The marginal reading is the normal one for virtually every MSS except Codex B here, and can be traced back to the 2nd century.

The lemniscus - ( ) here functions just like a modern insert-mark - (

) here functions just like a modern insert-mark - ( ), purely to indicate an accidental scribal error of omission at a specific point in the text.

), purely to indicate an accidental scribal error of omission at a specific point in the text.

Case 2: Line 38

Again, further down the page, another omission by homoeoteleuton (caused by similar endings of a line or phrase), has been caught, this time probably by the original scribe in proofreading his own work later. It is too late to erase whole lines and columns, so he opts for the easiest fix: a marginal note. Here too it is clear that the 'correction' is the original reading, and this is just a blunder during the initial copying.

Neither case is meant to suggest the readings should be removed, but rather that they are original and should be re-inserted.

This point is especially important, since in the first instance, the 2nd corrector (line 9) uses a diacritical marking known as a 'lemniscus' (a line and two dots). This mark is usually (as we noted in the LXX situation) interpreted to mean a 'critical' note or one which casts doubt upon a reading.

It completely strains all credibility to think someone would later add a known 'false' reading to an obviously already correct text, only to cast doubt upon that added reading by using a critical symbol in its 'normal' meaning. What has happened here rather is simply this:

The scribe uses the mark - a lemniscus (line and 2 dots) simply as a general indicator of a correction. It is otherwise of no significance, and is lexically empty in and of itself. The mark cannot be interpreted as an indication of a 'doubtful' reading, because its very usage shows it to have a very different meaning.

An important observation here with Vaticanus is that the corrections were done systematically, but AFTER the books were already written out. The corrections were added later during a 'proofreading' phase:

a) once by the original scribe, probably using his own original master copy; he does not apparently make use of special signs for these corrections, and

b) once by another hand, probably a monk in charge of inspection and quality control of manuscripts like this before they left the scriptorium. This person used the 'lemniscus' as a formal indication make an amendment in the reading.

In both cases, the marks were added later, but probably before the manuscript left the scriptorium and was sent to its destination

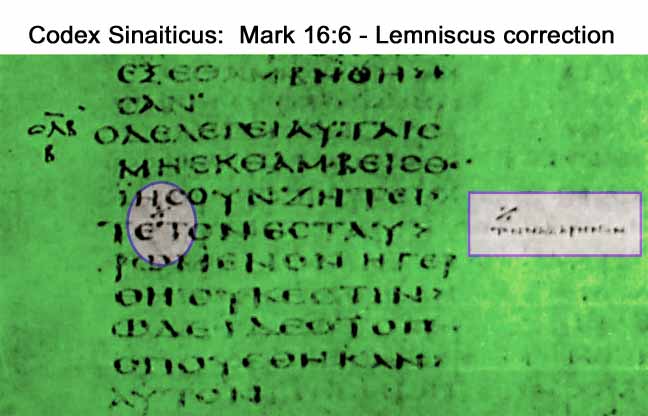

Nor is this standard use of the lemniscus restricted to Codex Vaticanus. We find the exact same usage and meaning in Codex Sinaiticus. Here for instance, in Sinaiticus at the ending of Mark (16:6), is a lemniscus indicating that the original scribe has dropped a phrase ("of Nazareth"). This has noted at the correct point in the line with a lemniscus, and the missing text has been added into the margin:

The Umlauts of Vaticanus:

In Vaticanus there is a third set of critical markings, call the 'Umlauts'. (the mark is a horizontal pair of dots, not shown here). In these cases no text was inserted in the margins, but only the place of a variation among the main versions was noted. These may have been intended to be used to add yet more footnotes later, or simply left as a quick guide for others to beware or be aware of the exemplar's peculiarities, and correct any new copies made to their own taste.

We can hardly leave our discussion of Codex B without examining the Umlauts found at John 7:53-8:12

Here we just want to remark that the Umlauts in the NT here are not really a surprise, or any different from the umlauts found in the Greek OT. There they were also used to indicate variants in the text.

But in the OT the alternate readings were not included in the text or margin either. The alternate readings could only be found by consulting Origen's original master-copy of the Hexapla, and checking the adjacent columns of other versions.

Here likewise, the umlauts tantalizingly suggest the existance of a 'master-exemplar' of the NT, probably prepared by Eusebius himself, possibly having several columns for parallel versions or margins for critical notes or readings. This master-copy, if it existed, is now lost.

What the scribe of Vaticanus has done is to copy the main column of this master-copy. The plan of Eusebius was probably to have his master-copy available for consultation in a way similar to Origen's Greek OT Hexapla, which was kept at the library in Caesaria.

This obvious usage of the umlaut has two consequences. In places where the longer reading was retained in the text, we would expect an 'end-marker' to follow it somewhere further on.

But in those cases where there was an omission of material by the editor, there would be no text to 'highlight', and no 'end-marker' would appear. Instead you would have the complete 'note' in the simple placement of the umlaut to mark the point where the missing text should be inserted.

Several good articles are available on this subject. We can point the reader to the following website which has made the articles available:

Bottom Line:

For Vaticanus at least, we can distinguish two broad categories of markings:

(1) simple corrections of scribal blunders, usually omissions, often marked with a 'Lemniscus'. It should be noted that although the scribe of Vaticanus has been characterized as a 'hopeless blunderer', and the manuscript itself called 'vile, demonic' etc., at least a third of the blunders (omissions) are apparently simply copied from the master manuscript from which it was made. This means that a large number of the 'blunders' are not by the scribe himself, and most could not have been caught without painstaking comparison to another authority during the first pass.

In the case of Vaticanus, it is clear that the copying and proofreading were separated into two different tasks or phases, to make the the process more efficient.

These mistakes are important, because they tell us clearly what either the original master-copy actually had in its text (the original mistake), or else they tell us what the scribes in the scriptorium knew or believed was the original reading (the correction) at that time (about 300-400 A.D.).

(2) The More Difficult and Legitimate Variants marked by the 'Umlauts'. These cases were such that the scribes did not feel authorized to choose between them, but nonetheless felt compelled to inform us of them by placing critical markings in the margins.

This was a way of not giving 'absolute authority' to any single manuscript or copy, but taking into account the state of the text as it was generally known at that time. It also allowed manuscripts which were known to be ancient and generally reputable at that time to be copied, even though 'errors' and variants were known to exist in them.

Again, these markings are an invaluable resource for getting a grip on the state of the text and the opinion of the scribes at this time in the history of the textual stream.

But the important point for our purposes here, is that even in the case of the great Uncials, for the New Testament at least, the critical markings were not usually used to indicate 'bad readings' in the text, but rather as insertion marks, or indicators of the existance of other variant readings generally. Contrary to the impressions of the critical literature, we can observe this:

- Only the umlaut fits the function of an 'obelus' in the Uncials. It marks a point in the text where the reading may be in doubt, because other variants are known to exist. But no alternate reading is offered: the reader is expected to check for himself.

- Jerome may have used a simple dash or horizontal stroke as an 'obelus'. But he probably never used a lemniscus. He certainly did not use any symbol as an 'obelus' in the New Testament sections of the Vulgate, but only applied such marks to the Old Testament.

- a lemniscus typically marks a place in the text for the insertion of a marginal note. It does not suggest the reading of the main text itself is an 'interpolation'.

Asterisks and Obeli:

Usage in the Miniscules

Now lets look at how the same markings are used some 8 to 10 centuries later, in the 9th and 10th centuries A.D.:

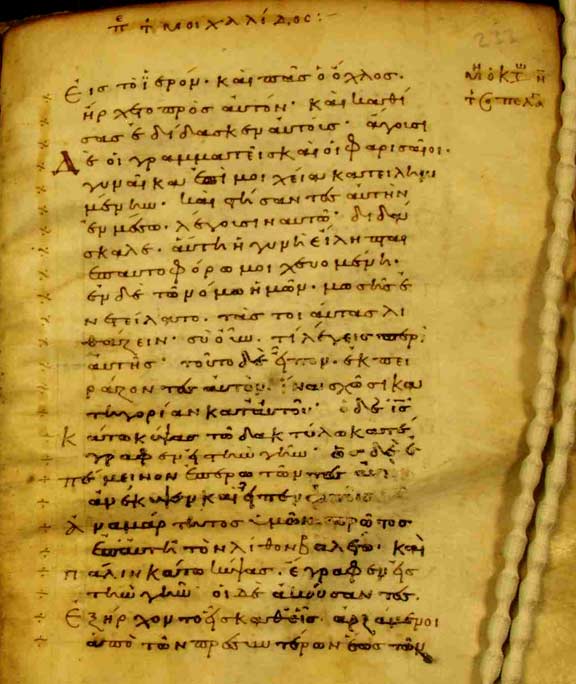

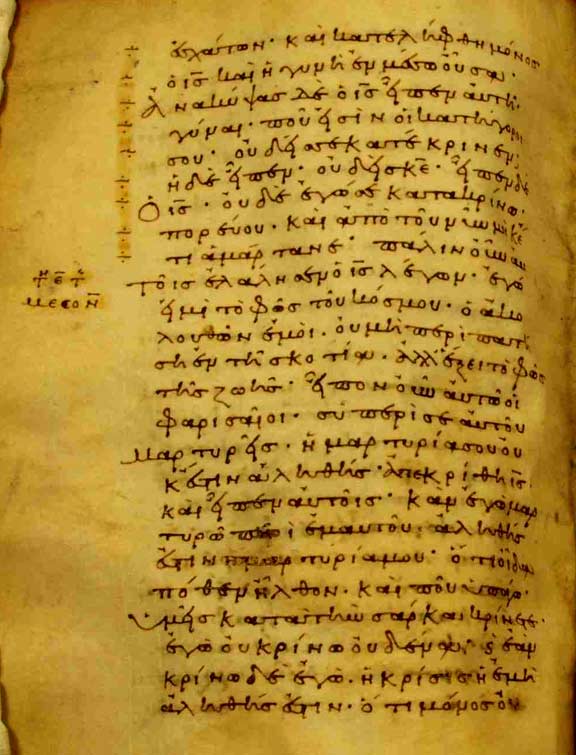

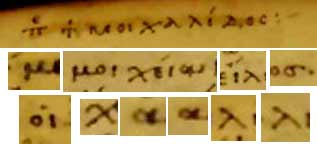

Example Miniscule # 2754: - John 7:53-8:11

A title has been added at the top, "MoixalidoV" (Adultery).

The 'annotator' starts marking the section down the left margin from the top of the page, although the pericope actually began on the previous page. This page begins about halfway into verse 8:2.

This seems sloppy, but the descrepancy is probably for appearance sake. The annotator is either using the Lectionary as a guide (it starts at 8:2) or just the physical page top. But neither case inspires any confidence in the corrector's acumen.

The short notes on the right are just lectionary notes, in the original hand (first copyist). These mark the beginning and ending of the section, for public reading on feast days. Note that these lectionary notes, are on the opposite side on page 1, but end up on the same side on page 2, again indicating two different hands.

He begins by using a 'twisted lemniscus' ( ) which has the appearance of a simplified asterisk. He may have chosen this symbol because of size considerations, and because a full asterisk would be too elaborate and troublesome to duplicate some 40 times, which was his plan.

) which has the appearance of a simplified asterisk. He may have chosen this symbol because of size considerations, and because a full asterisk would be too elaborate and troublesome to duplicate some 40 times, which was his plan.

Interestingly, he switches to a 'normalized lemniscus' ( ) about halfway down the first page, continuing with the new symbol till the end. This is doubly odd: To the casual browser (overseer?) asterisks will appear to have been added, but someone examining and reading more closely, the lemniscus 'switch' will be recognized and noted.

) about halfway down the first page, continuing with the new symbol till the end. This is doubly odd: To the casual browser (overseer?) asterisks will appear to have been added, but someone examining and reading more closely, the lemniscus 'switch' will be recognized and noted.

Finally, we may also note that the 'annotator' has smeared the whole column of marks vertically, to make them stand out boldly, or else added a coloured 'wash' over them. This seems a superfluous, almost childish action to draw attention to the marks, and may be unique in the history of marginal markings.

The Added Title:

A close look at the title reveals that it is most definitely by a second unknown hand: The title is shown at top, and samples of the original scribe's handwriting from the same page are shown below.

The title, a mixture of 'semi-capitals' and miniscule (script), plainly betrays a foreign hand:

(1) the original scribe (OS) prefers almost a textbook miniscule 'm' (mu).

(2) when writing 'oi', the OS always extends the 'i' below the 'o' (omicron).

(3) the OS writes 'a' (alpha) almost like a modern 'a', and never varies.

(4) when writing an 'x' (chi), the OS makes the down stroke a longer flowing curved (hooked) line, not straight.

(5) the OS writes his 'L' (lambda) splayed, that is, pyramidal, the legs always greater than 90 degrees apart.

(6) the lambda always has a very discernable knob.

(7) throughout the MSS the accents are always 45 degrees or flatter.

(8) the original scribe always writes 's' (sigma) as an omicron with tail, even on all word endings, never as a 'c'.

(9) the original scribe's (but not the corrector's) special larger flourished letters follow the same style.

Thus the annotator has hardly even attempted to imitate the OS, let alone disguise his hand. In a mere 10 letters or less, he has carelessly exposed himself.

Purpose of the Marks:

The asterisks (actually in this case a lemniscus) run all the way down the side of the section. This is precisely the same style of usage as was done in the O.T. (LXX) for Origen's Hexapla, and this is strong evidence that the person marking the margins had the same usage in mind as well.

We think the 'corrector' was emulating the Alexandrian School in his own fashion, and so his covering of the left margin with marks is not as 'special' as might be assumed. He still uniquely smeared the column, and remains 'heavy-handed' in his approach.

That is, this corrector may not have intended the passage be excised or cast in doubt at all, but rather, that special attention was to be drawn from its presence in the manuscript.

Lectionary Reader's Marks:

It should be understood that the majority of manuscripts of all types (if not originally copied for the purpose,) were put to use almost immediately and continuously in church services. In this use, the Holy Gospels were divided up into 8 or 12 verse 'pericopes' to be read and commented upon 'publicly' (that is, in the church service).

In Alexandria however, similar marks in the margin of manuscripts were also used to indicate critical editing or doubtful passages.

Naturally, on occasion the two systems of marking manuscripts were confused, and this is a quite plausible explanation for the dropping of a passage like John 8:1-11. Since, if the variant is an omission, it likely originated in Alexandria, it is a very probable explanation. An Alexandrian scribe, or even a whole scriptorium could have been uninformed or misinstructed as to the system of markings for public reading, and expunged the passage.

On the other hand, once the passage fell under suspicion in some quarters by having been found absent in some manuscripts (presumably the 'best' ones from Alexandria), then a comedy of errors would ensue.

And this is what we find: Many late manuscripts have the passage clearly in the original hand, yet, some unknown and untraceable second hand has then marked the verses, sometimes with a critical note.

The value of these amateur excursions into textual criticism by a handful of scribes or 'editors' is dubious if not worthless, since the notes come so late in the tradition, have no tracable authority or even identity or source, and are clearly not from the original scribe. Dr. Hort expressed the very same opinion himself, regarding critical notes in late manuscripts:

Hort:

"These [marks] and other scholia in MSS of the 9th (or 10th) and later centuries attest the presence or absence of the Section [Jn 8:1-11] in different copies: their varying accounts of the relative number and quality of the copies cannot of course be trusted."

(Hort, Notes on Selected Readings,Appendix, pg 83)

How Hort's observation here undermines his own grouping of 'marked' manuscripts as supporting omission hardly needs comment. This classification and use of late manuscripts is 'weak' to say the least. A careful re-sorting of MSS into 'for' and 'against' would seem mandatory at this point, along with cautions as to the strength of such 'evidence'.

Key points regarding the miniscules are:

(1) As is common, the markings are from a second hand, and not done by those who made the manuscript. Its makers it are only responsible for the Lectionary marks. They could have been added at any time by anyone, and we have no way of evaluating their authority or importance.

(2) The markings may have been intended to draw special attention to the presence of the verses, not for censure, or casting doubt. Even this is difficult to ascertain, but remains a strong probability, given the majority of marked manuscripts are marked with asterisks, not obeli.

Summary and Conclusion

Regarding the evidence of critical marks in the bulk of MSS of John's Gospel attached to the Pericope de Adultera,

Davidson (1848): "The verses are marked with an obelus in S, and in about 30 (other) MSS. They are asterisked in E and in 14 (other) MSS. ...It is very remarkable too, that so many MSS having it, affix marks of rejection or interpolation."

Scrivener: The passage is noted by an asterisk or obelus or other mark in Codd. MS, 4, 8, 14, 18, 24, 34 (with an explanatory note), 35, 83, 109, 125, 141, 148 (secunda manu), 156, 161, 166, 167, 178, 179, 189, 196, 198,201, 202, 219, 226, 230, 231 (secunda manu), 241, 246, 271, 274, 277, 284 ?, 285, 338, 348, 360, 361, 363, 376, 391 (secunda manu), 394, 407, 408, 413 (a row of commas), 422, 436, 518 (secunda manu), 534, 542, 549, 568, 575, 600. There are thus noted vers. 2-11 in E, 606: vers. 3-11 in P (hait ver. 6), 128, 137, 147: vers 4-11 in 212 (with unique rubrical directions) and 355: with explanatory scholia appended in 164, 215, 262 3 (sixty-one cursives).

From the literature, it appears that probably less than 70 manuscripts mark the verses with critical symbols, out of over a thousand that contain them. Of these, the ratio of 'Obelus' (if these are correctly identified) to 'Asterisk' is something like two to one, 2/1. The actual number of manuscripts then which are possible candidates for providing 'critical comments' is then probably less than 50 in all, out of over 1000.

We can say that about 5% of manuscripts possibly have 'obelus-like' critical marks. All of these are very late manuscripts, newer than the 10th century A.D., and can have little use in the reconstruction of the early history of the passage. As Hort remarked,

"These and other scholia in MSS of the 9th (or 10th) and later centuries...cannot of course be trusted." (Select Readings, pg 83)

From the detailed evidence available, it is also clear that grouping all the manuscripts together, regardless of the kind of symbol they have is also a methodological error. Some markings apparently functioned as simple 'underlining' marks, or like the highlighting of a modern book. Hort and others were mistaken to group all marked manuscripts under a rubric of 'evidence against authenticity'.

There is abundant evidence that Christian copyists, editors and scholars have used a variety of symbols in the margins to organize and categorize variant readings. Yet most of this evidence indicates an attitude of 'inclusiveness', or open-mindedness regarding variants, generally out of a concern for preventing a loss of or damage to Holy Scripture. This seems to be as much of a factor as the concern for maintaining its purity, or purging spurious accretions.

We simply don't find that the main intent of those using various critical marks was to 'mark passages as spurious'. This appears to be largely a modern fiction projected back upon the early copyists, and is an anachronism to the mindsets and historical issues of concern to ancient Christians.

Interestingly, most recent critics seem to have quietly dropped the issue of 'critical marks' in the margins of late manuscripts in presenting the evidence against authenticity for John 8:1-11. They seem to have arrived at a consensus that such flimsy and ambiguous data adds little to any serious discussion of the problem.

Maurice Robinson

on Diacritical Marks

Dr. Maurice Robinson is an expert textual critic and the only man who has personally collated ALL of the surviving 'continuous text' MSS as well as hundreds of lectionaries. Recently (1997), Dr. Robinson gave a similar judgment concerning the meaning and value of the so-called marginal marks beside the PA found in some MSS of John:

Exerpt from:

Preliminary Observations regarding

the Pericope Adulterae

based upon Fresh Collations of

nearly all Continuous-Text Manuscripts

and over One Hundred Lectionaries

Evangelical Theological Society

Fiftieth Annual Meeting

19-21 November 1998

Orlando, Florida

Maurice A. Robinson, Ph. D.

Professor of New Testament and Greek

Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary

Wake Forest, North Carolina 27587

"...

(10) MSS which are obelized apparently were so marked for lectionary-related reasons. This was also Van Lopik's conclusion, and seems certain to be correct.

Metzger greatly overstates the situation when he claims,

"Significantly enough, in many of the witnesses which contain the [PA] it is marked with asterisks or obeli, indicating that, though the scribes included the account, they were aware that it lacked satisfactory credentials."

The earliest obelized MS is E/07 of century VIII, from a time in which the lectionary system was already fully implemented. The next cases of obelization are 5 MSS in century IX (Λ/039, Π/041, Ω/045, 399 and 2500), followed by 11 MSS in century X, 47 MSS in century XI, 34 MSS in century XII, 46 MSS in century XIII, 86 MSS [!] in century XIV, 33 MSS in century xv, and 13 MSS in century XVI, with one MS each in centuries XVII and XVIII.

The large number of obelized MSS in the later centuries are directly related to the growth of the so-called Kr text (discussed below), and are clearly tied to the lectionary equipment which characterize the MSS of that subtype.

In view of the utter lack of obelization before the 8th century, Metzger appears to have assumed a far greater scribal interest in text-critical matters than such a late date warrants and [this assumption] anachronistically projects Alexandrian classical philological concerns into an era in which they no longer apply.

Metzger also neglects the converse: in contrast to the 16 MSS which obelize through the 10th century, there are 46 MSS within the same time period which contain the PA and indicate no trace of doubt" regarding its authenticity (if obelization even were to indicate such).

The "obelization rate" among PA MSS through century X is 17/62 = 27%. Should the time frame be reduced to only the 9th century and earlier, there remain 8 non-obelized versus 6 obelized MSS which contain the PA - an obelization rate" still of only 6/14 = 43%.

It is far easier to understand the obeli as serving their proper purpose as instructional aids to the lector when having to skip over a portion of text which was not part of a given lection than to presume a sudden upsurge in text-critical acumen during a low point within the medieval period in which textual criticism was not of as much concern as in the early era of MS transmission.

Based on these data, it is highly unlikely that the Alexandrian/Egyptian MSS which exclude the PA did so through a misreading of early obeli as a sign of omission or possible inauthenticity in terms of classical Alexandrian text-critical scholarship.

There simply is no evidence of pre-8th century obeli within the extant MS base. This does not, however, rule out omission of the PA in those pre-8th century early witnesses due to lectionary considerations which required the skipping of portions of NT text and which may have affected their local archetype.'

...

- Maurice Robinson