Codex Monacensis

10th Century Gospel Commentary

Background

Being one of the first 'ancient' manuscripts ready to hand, which drew the attention of textual critics in the 1900's, The Codex Monacensis was given a Capital Letter for a symbol (X), and counted among the other old Uncial (or 'Majiscule') manuscripts known at the time (These were assigned letters: A, B, C, D, etc.). It was not numbered among the Cursives (Miniscules), because it contained a mixture of "Uncial"-like printing (Capital Greek letters) and "Cursive" (relatively modern) handwriting.

The manuscript however, is neither an "Uncial" (ancient hand-printed copy in capitals) nor is it even a 'continuous copy' of the Gospels. It is actually a Commentary, apparently originally written by Chrysostom (5th cent.) or borrowing from him, but somewhat modified. It has been dated to either the late 9th or early 10th century.

(Excepting it contains Mark without commentary, presumably to complete the set of four Gospels, or else to preserve a copy of Mark in passing, or to provide the text for a future commentary on Mark.)

Dean John Burgon was one of the first to bring to attention the fact that this was not an ancient "Uncial" at all, and should not be quoted in any critical apparatus as if it was one:

"...[Codex] X, being a commentary on the Gospel as it was read in church, of course leaves the passage out."

- John Burgon, The Causes of Corruption of the Traditional Text of the Holy Gospels, ed. Edward Miller (1896, London - George Bell and Sons) Appendix 1: The Pericope De Adultera pp. 232-265

To our knowledge, the only people to correct this oversight in any critical apparatus is the NETBible, in their online textual notes, by their quietly omitting the citing of Codex X regarding the omission of John 7:53-8:11.

Codex Monacensis (X/033)

10th Century Gospel Commentary

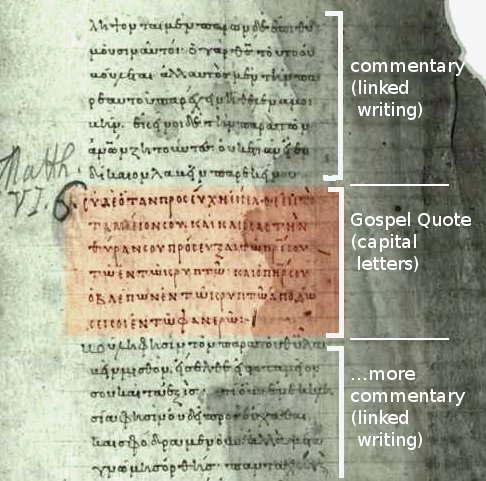

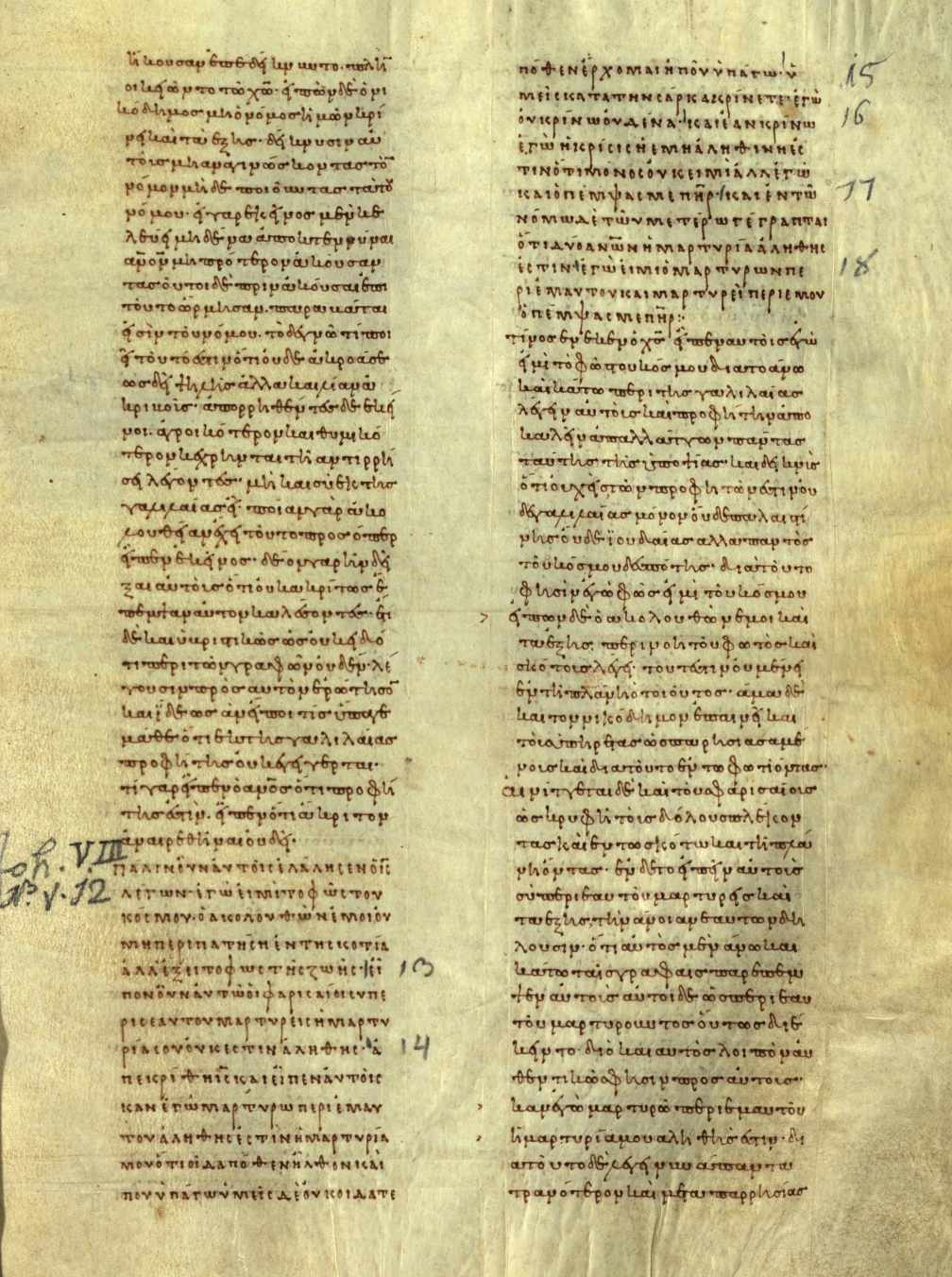

A portion of Page 5 (photo 8, the 3rd surviving page) shown below, illustrating the cursive script (small connected handwriting) used for the commentary portion (of Chrysostom), and the contrasting capital script ('pseudo-Uncial') used for NT quotations. Here the Quotation of Matt. 6:6 is being highlighted to show the change in 'font style' used to indicate quoted text.

This is not 'real' Uncial script, nor was it intended to deceive. It is written in the same size as 9th-10th century Cursive, and was used decoratively and functionally, to mark off quotations. There should be no danger of anyone mistaking this text or any part of it for an ancient (4th century) Uncial manuscript.

Tregelles described this handwriting as follows:

[the letters are] "small and upright; though some of them are compressed, they seem as if they were partial imitations of those [letters] used in the very earliest copies."

Codex Monacensis (X/033)

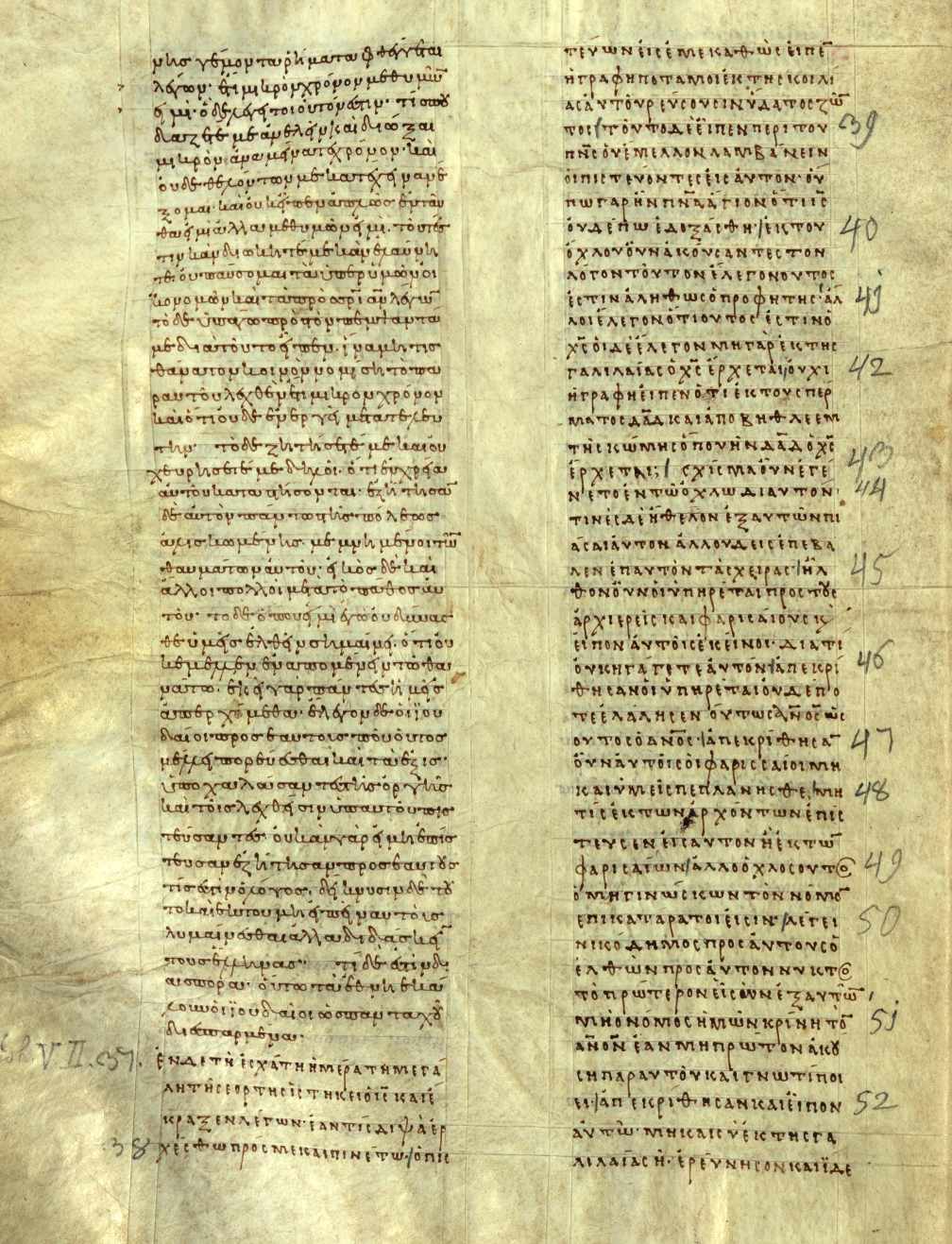

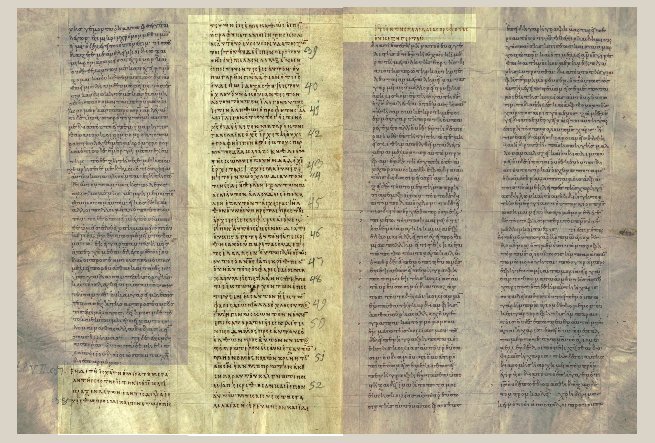

Page 38-39, Showing John 7:37-52

Page 38: Larger view

Page 39 (i.e., opposing page) Below:

The last half of the final verse John 7:52 (without the transition verses, 7:53-8:1) is shown at top of left column in 'pseudo-uncials'. The scribe here in the Johannine section is simply copying the Commentary, including the quotation. In John at least, the source of the text is likely the just the commentary itself. Chrysostom's text was probably Byzantine, as known in the 5th century.

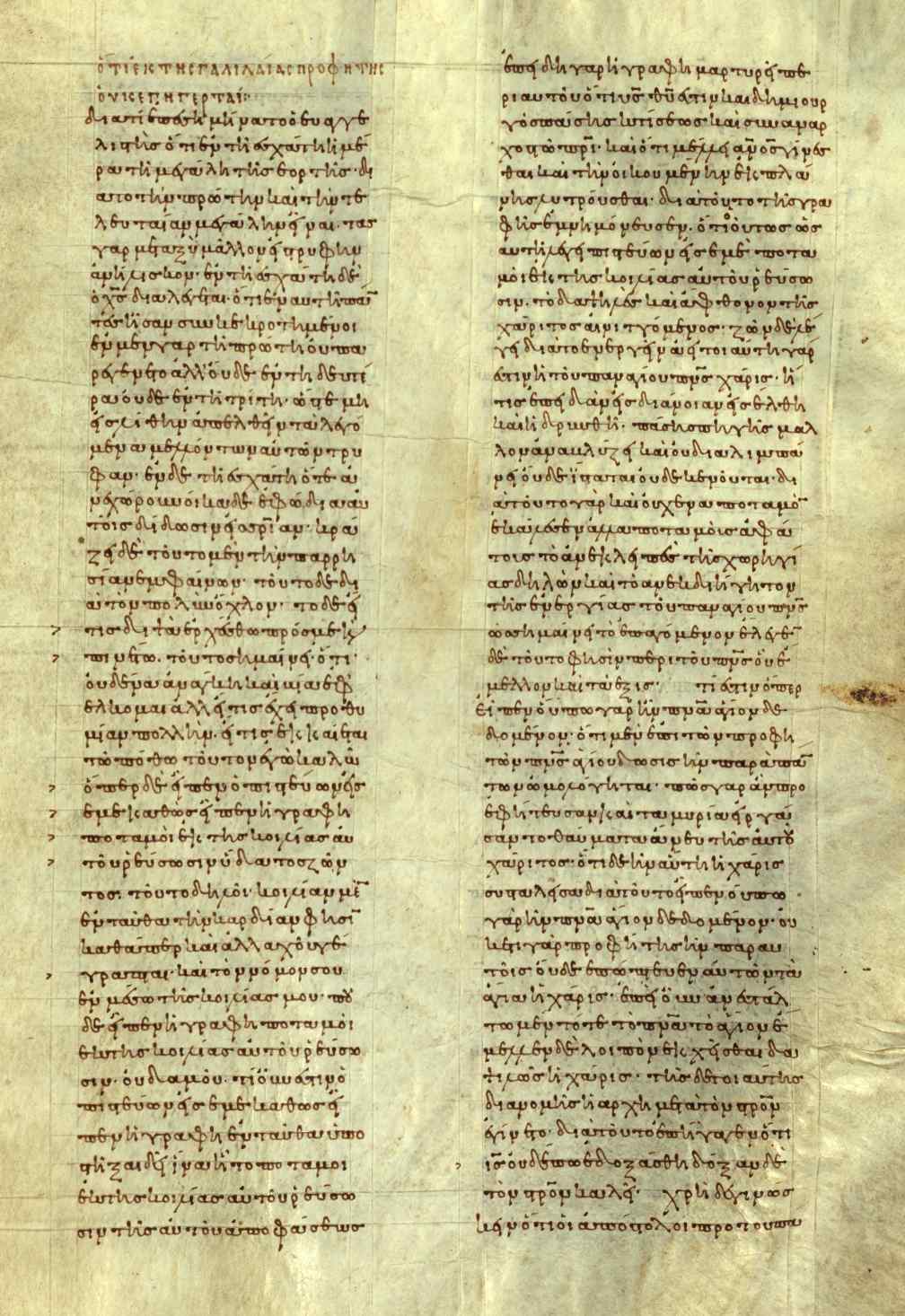

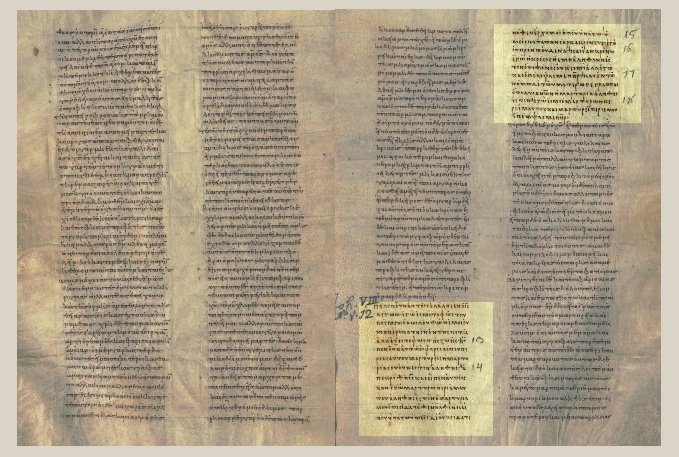

Pages 40-41, Showing John 8:12-17

Page 40 (i.e., left page) Below:

Now follows another page (and a half) of commentary on the previous verses (Jn 7:37-52). The text of John has been divided into pericopes for the commentary. The great church commentaries by Chrysostom and other Church Fathers were originally composed for public reading (Sermons), and followed the Greek Lectionary Calendars. During Easter, Jn 7:53-8:11 (The Pericope de Adultera) was skipped over, and the next section read to the congregation began at Jn 8:12-18 (The "Light of the World" Dialogue). The reading of the Pericope de Adultera was postponed for Feast Days in the Fall (e.g. Oct 8th).

Page 41 (i.e., right-hand page) Below:

After the Commentary on Jn 7:37-52 ends, the new section to be read during the Easter Week begins at the bottom of column I below and continues (in 'pseudo-Uncials') for 11 lines in column II. Then follows the commentary (in miniscule script) on Jn 8:12-17.

Summary

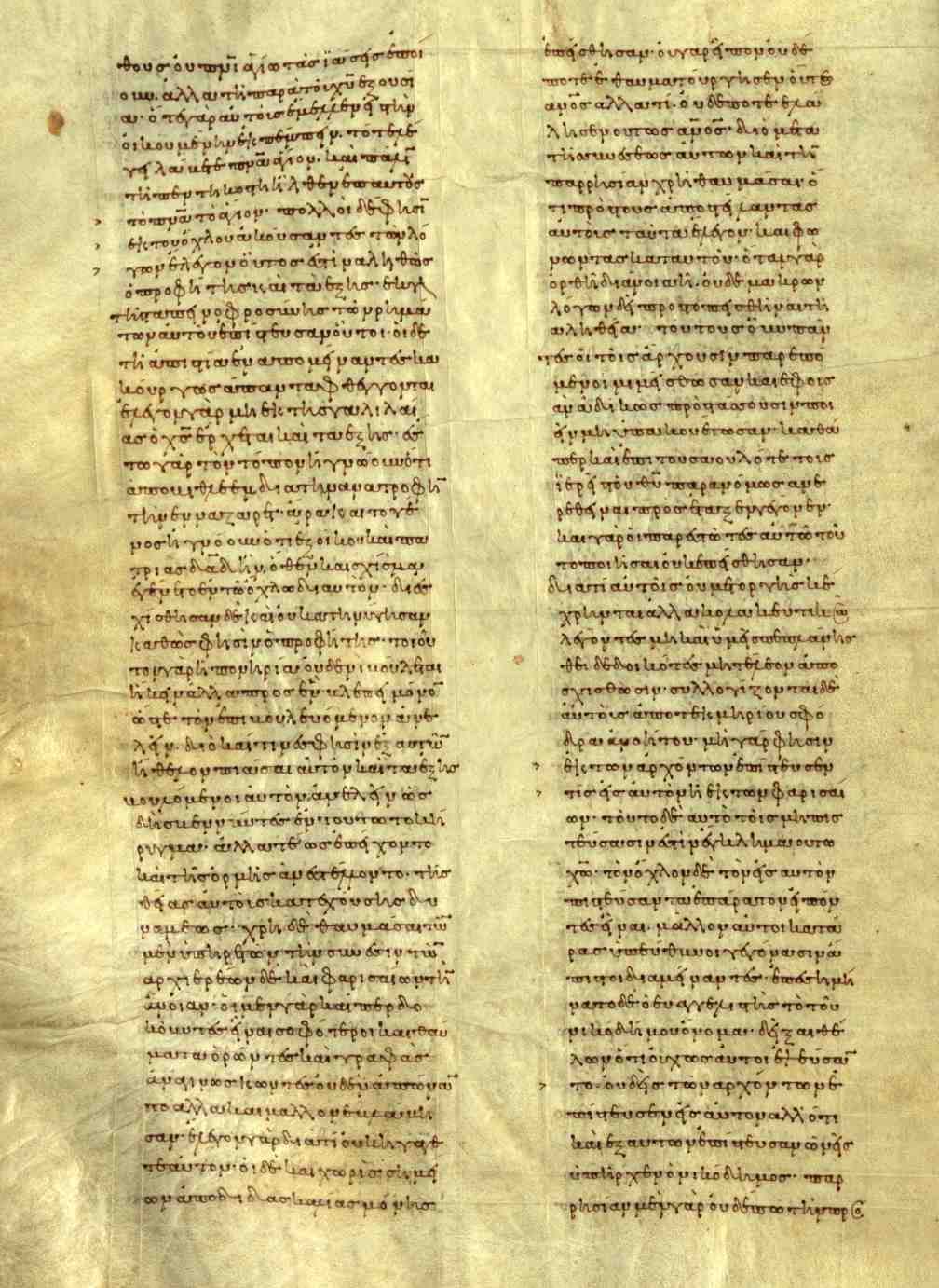

In the Johannine Sections at least, Codex X is nothing more than a late copy of an edited commentary by Chrysostom, although the Gospel text probably reflects the Byzantine Text-type as used in the 5th century by Chrysostom himself. On the other hand, since the commentary has been edited, it is likely the text has also been 'modernized' by the 10th century copyist responsible for the manuscript, or a previous editor.

Obviously it is grossly misleading to imply (e.g. using the symbol "X" without comment) that Codex X is an ancient Uncial manuscript, when it is really a 10th century copy of a 5th century commentary. It is also misleading to list this manuscript as "omitting" John 7:53-8:11, when in fact it does not present a continuous or complete copy of John at all, but only quotes it in sections, following the established Lectionary/Menology tradition of reading key portions of the Gospels throughout the Ecclesiastical Year.

Further Debate

(From Evan.TC Blog, 2010)

The following discussion is taken from:

ETC Blog Article comments < - - Original posts.

W.Willker's Post 1:

"Codex X/033 is a continuous text manuscript. I have collated it for the online commentary.

It is only debatable if it should be considered an uncial manuscript, but that doesn't matter much.

It is noteworthy that X is only about 50% Byzantine in John, comparable to 33.

I posted some comments on the manuscript here.

...Jn 19:14 is cited in the text as "it were the third hour". Several other witnesses read so, too. The commentary has "it were the sixth hour", noting explicitly the difference between Mark and John.

7:57 AM, May 26, 2010

W.Willker's Post 2:

"Please show one instance where the Gospel text in X is not continuous (except for the missing folios). Codex X is a commentary manuscript and the commentary is not continuous. But the Gospel text is continuous.

This is all clear and straightforward. There is no confusion. The PA is not in the text."

2:02 PM, May 28, 2010

Nazaroo Replies:

I want to respond directly to Mr.Willker's last post, because his questions are serious and important.

But first let me recap the essential issue, to show how the 'confusion' element enters.

There are three key questions:

1. What exactly is "codex X"?

2. Is it relevant evidence re: the PA? And if so, how?

3. How should it be cited in an apparatus, if at all?

Lets take question 1:

1. What exactly is "codex X"?

(1) The Physical Layout and Content of Codex X

W.WIllker categorizes the document:

"Codex X is a commentary manuscript."

Codex X is a composite document, alternating short Gospel sections with accompanying commentary. The Gospels and commentary were originally separate documents, later copied in combined form. Each Gospel was split apart into sections and likewise the commentary, then they were matched up and alternately block-copied in A/B/A/B fashion to create a new document.

Further we may note it has been written on expensive parchment, in neat narrow double-columns of constant width, and was probably made for use in public reading, for comment on the Gospel sections being read during services. This was not a private book, but would have belonged to a local parish or bishop.

(2) The Handwriting & Style of Codex X

A portion of Page 5 (photo 8, the 3rd surviving page) shown below, illustrating the cursive script (small connected handwriting) used for the commentary portion (of Chrysostom), and the contrasting capital script ('pseudo-Uncial') used for NT quotations. Here the Quotation of Matt. 6:6 is being highlighted to show the change in 'font style' used to indicate quoted text.

Tregelles described this handwriting as follows:

[the letters are] "small and upright; though some of them are compressed, they seem as if they were partial imitations of those [letters] used in the very earliest copies."

This is not 'real' Uncial script, nor was it intended to deceive. It is written in the same size and hand as the rest, and was used decoratively to mark off quotations. There is no risk of mistaking this for ancient (4th century) Uncial script.

(3) The Dating of the Text of John in Codex X

W.Willker has collated X for his own commentary. He tells us:

"It is noteworthy that X is only about 50% Byzantine 1 in John, [and is] comparable to [the 11th cent. miniscule MS] 33." 2

Codex X' John then appears to be a 10/11th cent. 'mixed Byzantine' text. 3

If so, most textual critics view such late copies of late mixed texts to be of little value for textual criticism. What we do know however, is that during the 8th-9th centuries 70% of copies of John contained the PA (Jn 7:53-8:11). 4

1. Historically speaking, the practice of 'quantifying' texts by a "% agreement" has been plagued with ambiguity in meaning, inconsistency in method and unreliability in result. Until Mr. Willker gives more details, "50%" is best viewed as a guesstimate.

2. Manuscript # 33 - is listed incorrectly as 9th cent. in UBS-2. Although the O.T. portions may be 9th century, the NT portions are by a later hand dated to the 10th or 11th. (See both Gregory, & Scrivener). If Codex X is comparable to 33, this again links its production to the 10th/11th century. Mr.Willker may want to associate Codex X with 33 because 33 omits the PA, although this is the exception for this period, not the rule.

3. This may hint at when the text/commentary combo was put together (i.e., post-11th cent.).

4. From the 10th century onward, over 90% of copies contain the PA.

(4) The Classification of the Text of John in Codex X

Nazaroo:

"Codex X contains a near-complete 'continuous-text' copy of John."

This expression makes two necessary distinctions:

(1) 'continuous-text' is in single-quotes to make clear that we are only categorizing the type of text it contains, not the quality, accuracy, or value of that text.

(2) Codex X itself is NOT a 'continuous-text' MS, nor is it a simple copy of one. Key features of that text have been lost because of how Codex X has presented that text.

This second part b) of the question is precisely where the 'confusion' element enters, and that is why Mr. Willker's less precise expression is inadequate.

Mr.Willker says, "But the Gospel text is continuous.";

But he uses 'continuous' here as if it were an ordinary adjective implying something about the text itself, whereas what is needed is to make clear that categorizing the text-type as "continuous-text" does not and should not imply anything about the contents or quality of its readings, or even what we may be able to know about them from the physical form of the text given by codex X.

The issue was never about how the manuscript has been classified by a bunch of self-appointed German critics, or any minor quibble about what the definition of a "continuous-text" MS is.

The Definition of "Continous-Text MS"

But for what its worth, its not *us* who have misunderstood the meaning or significance of the classification of X as a 'continuous-text MS'. We have understood it perfectly well and uphold the 'standard' definition, which is this:

This designation means simply that a manuscript contains a text which has not been edited or modified so that the sections can be used as "stand-alone" lections.

*non*-"continuous-text" MSS divide the text into sections which are then modified at the beginning and end of each section, so that each can function as an independant story unit, and be read in isolation publicly in church.

The purpose of the classification is not to indicate how complete the MS is as a copy, nor even to indicate whether the text has been divided up into sections physically, or marked off. Nor is the designation intended to indicate the quality of the text-type, other than whether or not it exhibits this special editing feature.

The reason for the interest in alterations at the beginning and end of each section is that the presumption is that the gospels were originally "continuous-text" in this sense, and that the 'pericopizing features' are in fact secondary.

The classifcation of Codex X as "continuous-text" implies nothing more or less than the absence of these specialized features at the beginning and ending of each standard section (well-known from the Lectionary tradition). It does not indicate (as the language of W. Willker, P. Head, and T. Wasserman wrongly suggests) anything else about the quality or text-type contained in the manuscript, or its physical layout or completeness.

This (distracting) side-issue being finally dealt with once and for all, lets move back to the real topic at hand.

Nazaroo Replies:

Now look at question 2:

2. Does "Codex X" offer any evidence regarding the PA?

Finally Mr. Willker poses a challenge. What he means by "continuous" is partly revealed in the following phrases:

"Please show one instance where the Gospel text in X is not continuous (except for the missing folios).

...the commentary is not continuous.

But the Gospel text is continuous."- W. Willker

Mr. Willker's idea here is that if John in codex X is continuous, and the PA is missing, then the copy used must have omitted the PA.

But this suggestion is both inaccurate and circular, and deliberately confuses two different meanings for "continuous" in this context.

The commentary is indeed "not continuous", in the following sense:

The commentary does not comment on every verse of John.

Here any version of John will do as the standard of comparison. The minor variants in the Codex X text don't affect the result.But what do we measure the text of John against?

Nazaroo Replies:

The text of John in Codex X is *NOT* continuous, if by that we mean what any reasonable person would assume by such an expression.

Just as the text of the commentary is not continuous, that is not physically contiguous, but interspersed in blocks with the text of John, so equally is the text of John not physically contiguous, but interspersed in blocks with the text of the commentary.

Each text is physically chopped up into sections and placed alternately in blocks, A/B/A/B throughout the manuscript.

Just where we would like to know if the text of JOHN actually was contiguous in the original exemplar, (i.e., running continuously from 7:52 to 8:12), the text has been physically chopped up and placed in separate blocks.

Thus we can never know whether the Gospel used by the compiler had the PA or not.

regards, Nazaroo