Prologue

Concerning the "Caesarean Text"

In recent years many scholars have expressed doubts about the existence of a "Caesarean text." In 1963 Bruce Metzger surveyed the history of investigations up to that time and concluded,

"By way of summary, it must be acknowledged that at present the Caesarean text is disintegrating. There still remain several families--such as family 1, family 13, the Armenian and Georgian versions--each of which exhibits certain characteristic features. But it is no longer possible to gather all these several families and individual manuscripts under one vinculum such as the Caesarean text.

The evidence of P45 clearly demonstrates that henceforth scholars must speak of a pre-Caesarean text as differentiated from the Caesarean text proper. Future investigators must take into account two hitherto neglected studies, namely Ayuso's significant contribution to Biblica in 1935, in which he sets forth fully the compelling reasons for bifurcating the Caesarean text, and Baikie's M. Litt. dissertation in 1936, the implications of which suggest that the Caesarean text is really a textual process."

(Chapters in the History of NT Textual Criticism

[Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1963], p. 67.)

More recently, Kurt Aland has expressed an even more skeptical opinion. He acknowledges only the Alexandrian and Byzantine text-types. While the "theoretical possibility" of a Caesarean text-type "must be conceded," Aland says that it is "purely hypothetical." He warns that text-critical arguments which are based on the idea of a Caesarean text-type are "based on dubious foundations, and often built completely in the clouds." (The Text of the NT [Eerdmans, 1989], pp. 66-7). --M.D.M.

-Bible Researcher,

www.bible-researcher.com/kenyon/stb14.html

Kenyon on

The Caesarean Text

Taken from: Sir Frederick Kenyon,

THE STORY OF THE BIBLE

Headings have been added for clarity and navigation purposes.

Chapter 8:

The Age of DiscoveriesThe Caesarean Text-Type

The next stage of our textual history affords an interesting example of the results of intensive study completed by happy discovery. While the search for early manuscripts of the Bible was proceeding, with the results already described, scholars had not neglected the study of the later manuscripts, on the chance of some of them having preserved traces of early types of text.

Family 13: The Ferrar Group & John 8:1-11

So far back as 1877 two Irish scholars, W. H. Ferrar and T. K. Abbott, had published a study of four manuscripts which presented some peculiar features. Three of them were written in Southern Italy in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the fourth, now at Leicester, was written in England in the fifteenth century, but was evidently copied from a parent of the same family as the other three.

The group is known as Family 13, from the number given in the lists to the first of them, or as the Ferrar Group, from the scholar who first called attention to them. They were plainly related, having peculiar readings which were not known elsewhere, or were only paralleled in very early manuscripts. A few other manuscripts were afterwards found to have traces of the same type; but it was not clear what significance or importance was to be attached to the peculiarities of a relatively late group, as to which all that could be said was that it seemed to have some affinity with the Old Syriac version.

Its most outstanding variant was that it transferred the incident of the woman taken in adultery from St. John's Gospel (to which it certainly does not belong, being quite different in style and language) to a place in St. Luke, after 21:38.

Family 1: The Lake Group

Another little group of four manuscripts was similarly isolated by Professor Kirsopp Lake, who published an account of them in 1902. It is headed by the manuscript which stands first in the catalogue of minuscules (and was slightly used by Erasmus), and is therefore known as Family 1. It preserves many readings which are found in early manuscripts such as the Vaticanus and Siccaiticus and Codex Bezae, or in the Old Syriac version, and Lake noticed that its peculiarities were most frequent in St. Mark, where it also seemed to show some affinity with Family 13.

Once attention had been called to this point, it was observed that in other manuscripts also St. Mark seemed to have been less affected than the other Gospels by the process of revision which produced the Byzantine text. The reason no doubt is that St. Mark, being the shortest Gospel, and containing less of the teaching of our Lord, was less often copied in early days and consequently less subject to alterations either by copyists or by editors.

We have already seen that St. Mark displayed special characteristics in the Washington Codex, and we shall find the same in some other discoveries which have yet to be described.

Family Theta (Θ): & The von Soden MS

The next step forward came from an unexpected quarter. In 1906, Professor von Soden, who was engaged in a very comprehensive edition of the Greek New Testament, called attention to a late and uncouth uncial manuscript. (now at Tiflis) which had belonged to a monastery in the Caucasus called Koridethi.

It did not seem to be earlier than the 9th century and its scribe evidently knew very little Greek; but perhaps for this very reason he was not likely to make alterations (though he might and did make many mistakes) in the text he was copying, and he had certainly preserved a somewhat unusual text.

von Soden associated it with Codex Bezae, but in this he was certainly wrong; and when it was eventually published in full, in 1913, it was pointed out by Lake and others that at any rate in Mark it had strong affinities with Families 1 and 13.

The next stage therefore was to combine this manuscript (to which the letter theta Θ was assigned in the catalogue of uncials) with those two families, and to designate the whole as Family Theta (Θ).

The Caesarean Text-type: Streeter's theory

The significance of the little Ferrar Group was thus evidently growing in importance, but it took on altogether, a new aspect where in 1924 Canon Streeter published (in his book The Four Gospels) the results of his researches into it.

After emphasizing the connexion of this Family Theta with the Old Syriac version (which was a proof of its antiquity, in spite of the relatively late date of the,manuscripts preserving it), he established the remarkable fact that the great Christian scholar Origen (who,died in A.D. 253) had in his later works, written after his removal from Egypt to Caesarea in A.D. 231, used a text of this type.

Caesarea in Palestine was a noted centre of Biblical study, afterwards famous for a library of which the manuscripts used by Origen formed a conspicuous part, which was much used by St. Jerome, and in which there is good reason to believe the Codex Sinaiticus was at an early stage in its history.

Streeter's conclusion therefore was that whereas Origen in his earlier works, written in Egypt, had used manuscripts containing the Alexandrian or Neutral type of text, he had found at Caesarea a different type which he had accepted as superior and had thenceforth used, and which for us was represented by Family Theta. He accordingly gave this family a new name, as the `Caesarean' text, to be equated with Hort's `Neutral' and `Western' as a family of first-rate importance.

This seemed to be a neat and compact, as well as important, result whereby the original insignificant Ferrar Group, of unknown origin, had been transformed into the Caesarean text, backed by the authority of the greatest scholar of the early Church, and comfortably housed in Palestine, in appropriate proximity to the Church of Syria.

Lake's Modifications to the Theory

It was, however, almost immediately disturbed; for Professor Lake showed that, on a closer analysis of the quotations in Origen's writings, it appeared that in his first works produced after his migration to Caesarea he unquestionably used an Alexandrian text, and only later changed over to the Caesarean. There is also some indication (though weak, for lack of sufficient evidence) that in his last work at Alexandria he was using a Caesarean text.

While therefore it may be legitimate to label this text as Caesarean, as having been used there by Origen and his disciple Eusebius, the truth may be that Origen brought it with him from Egypt, that he found manuscripts of the Alexandrian type at Caesarea and for a time used them, but then reverted to the Caesarean and thenceforth Adhered to it.

Streeter's Connection to the Washington MS & the Georgian Version

Another useful point made by Streeter was that the Washington Gospels might be added to the growing list of Caesarean authorities in respect of the greater part of St. Mark, the character of which, as indicated above, had hitherto been unidentified. The Georgian version has also been shown to be Caesarean in character; and if, as is probable, the Georgian version was derived from the Syriac, this is further evidence for the connexion of this type with Syria.

From all these discussions and discoveries one certain fact emerges, that the Caesarean text is now a definitely established entity, the character of which demands the further close study which it will undoubtedly receive from scholars.

Footnote on Family 13

The actual text of Family 13, which undoubtedly contains ancient readings and other elements, must be clearly distinguished from the practices of both the omission of the Pericope de Adultera (John 7:53-8:11), and its later re-insertion at Luke 21:38. This latter development can only be traced back to the 8th or 9th century, at a time when in certain monasteries, the passage was either being mistakenly expunged on the basis of current local opinion, or else others were attempting to reconstruct the text by re-inserting it in MSS which lacked the verses.

As von Soden long ago noted, in some cases, a lack of a master-copy containing the verses forced copyists to turn to the Lectionary and copy the passage from there. As a result of consulting the Lectionary version of the passage, sometimes confusion arose over what verses to include/exclude, and possibly where to place them.

Another stong possibility regarding Family 13, which uniquely tries to insert them in Luke, is that a copyist in the Middle Ages was ordered to leave them out, but could not bring himself to completely delete them, and so hid them in Luke as a way of preserving them without detection. There must have been strong debate and contention over the omission or inclusion of these verses, and this is what the evidence seems to reflect.

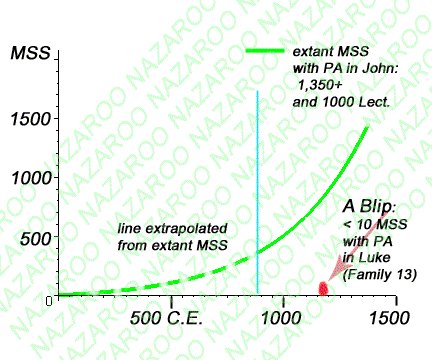

Nonetheless, the actual insertion of these verses in Luke is a very late practice, as the following chart illustrates: