INTRODUCTION

Peer Review:

... "In chapter seven (192-198) Hernandez summarizes his findings and conclusions. He points out that the traditional view that the scribes “tended to add rather than omit from their texts” has been called into question and that there “is the tendency to omit rather than add to their texts” instead (193). According to Hernandez this might have consequences for a more critical attitude towards the lectio brevior potior criterion applied in textual criticism.

Although all three codices show a general tendency of harmonisation, in Ephraemi harmonisations only appear in the immediate context, while in Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus harmonisations are also applied to more remote contexts.

Besides, Hernandez identifies anti-Arian scribal tendencies in Sinaiticus; but these need further reflection and discussion in studies to come in order to guarantee that they will not be a result of (modern) interpretation, as their evaluation depends on the standpoint and interpretation of its interpreters. ... By providing lists of the singular readings of the three codices under discussion, Hernandez does his readers a fine service (appendices 1 to 3; 199-218).

Experts in the field of NT textual criticism in general and scholars who specialise on the Greek text of the Apocalypse in particular will certainly challenge Hernandez’s classification of scribal habits in regard to singular readings, i.e., whether some of the harmonisations he identifies are actually harmonisations at all or could be qualified in an alternative way here and there, or whether the singular readings really have exactly the theological concern Hernandez wants to identify in them (see also, as delineated above, his identification of anti-Arian tendencies in Sinaiticus).

In addition, it is not evident from the study how Hernandez fancies that the copying process of manuscripts took place and how he imagines the conditions for that process in the 4th and 5th centuries.

These are two areas that may equally offer a plausible explanation of scribal errors or inconsistencies in some individual instances. Possibly, more palaeographical details could also have helped to get closer to the scribe as an individual with a certain educational and social background. This would have been only natural, because the scribes’ theological ideas are addressed anyway in Hernandez’s study. Be that as it may, the future will show what impact Hernandez’s fresh study will eventually have on the discipline of textual criticism.

But without doubt, Hernandez has shown that traditional criteria need to be challenged continuously so that they are not taken for granted and applied automatically. He is also to be thanked for having stressed that scribes are not copying machines but human beings with certain backgrounds, ideas, beliefs, and a desire to do things right.

There is no doubt that this study supplies information with which further work on the Greek text of the Apocalypse will have to take account and that it provides essential food for thought for NT textual critics.

Thomas J. Kraus

Federal Republic of Germany

t.j.kraus@web.de

M. Robinson on Hernandez

Dr. Maurice Robinson has also commented on Hernandez' work at the Evangelical Textual Criticism Blog Site:

'Sounds to me like déjà vu all over again (cf. M. A. Robinson, “Scribal Habits among Manuscripts of the Apocalypse”, PhD diss., 1982). However, it’s always helpful to improve the wheel, even if in some ways reinventing it.

There are differences, of course: my research dealt with the singular readings of all Apocalypse MSS collated by Hoskier, taken from ten scattered chapters throughout the book (to have considered all singular readings found in ca. 220 MSS necessarily would have exceeded dissertation limitations). My research thus led to conclusions drawn from a broad range of material as opposed to Hernandez’ more limited analysis of the three leading uncials (pity that he did not include the more extensive papyri

— I deliberately chose to add P47 to my study because of its significance, and today would add P115 in particular).

Equally, I certainly discuss the same MSS analyzed by Hernandez: A/02 (pp. 104-113), characterized as a “less careful editor”; C/04, “a careless scribe / careful editor” (pp. 113-118); and in extenso, Aleph/01 as “an editor to be reckoned with” (pp. 135-182).

In general, my conclusions are the same as those of Hernandez:

“the scribes of these three manuscripts omitted more often than they added to their texts, [and] were prone to harmonizing.”

- Maurice Robinson, Evangelical Textual Criticism Blog,

Royse on

Hernandez

James Royse (2008) also reviews Hernandez' 2006 study on Codex א, A, C, and concludes:

The Shorter Reading?

Add. Word

CountAver.

WordsOmit. Word

CountAver.

WordsWord

RatioAver.

Ratioא 40 66 1.65 49 116 2.37 1.7576 1.4364 A 12 13 1.08 17 34 2.00 2.6154 1.8519 C 5 6 1.20 21 30 1.43 5.0000 1.1917 Of course, besides those ratios another way to make the comparisons is to look at the net # of words lost in the additions and omissions, either as a total for the manuscript or per significant singular. Here Hernandez presents a perspicuous table: 112

Sing.

Addit.Sing.

Omit.Net

Words

LostTotal #

Sig.Sing.N.W.L /

S.Sא 40 49 50 158 .32 A 12 17 21 60 .35 C 5 21 24 43 .56

Whichever way we choose to view the data, of course, we see a tendency to omit. However, the scribes have their distinctive patterns.

Codex א has quite a few longer omissions (including 2 of 12 words at 16:2 and 16:13b, and 1 of 17 words at 20:9-10a), and so its scribe's average # of words per omission is the highest of these 3 scribes. 113 But the scribe omits not quite 5 times for every 4 times he adds.

On the other hand, Codex C omits at most 3 words at a time (at 12:14b and 14:4), and so has the smallest average # of words per omission, but its scribe's tendency to omit at all rather than to add is the most pronounced of the 3: the scribe is more than 4 times as likely to omit than to add.

Hernandez places his results within the context of the discussion of the status of the canons of the NT textual criticism:

"The text-critical principle lectio brevior potior has long been considered a useful and reliable criterion for deciding between competing variants in the Greek NT. The assumption behind this principle is that scribes tended to add to there MSS, rather than omit."

Hernandez continues by saying that my [1981] dissertation...

"...has amply demonstrated that the evidence of the early papyri simply does not support such an assumption about scribal activity. The present study has found that the assumption is also without warrant for the 4th and 5th century transcriptions of the Apocalypse in the Codex Sinaiticus (א), Alexandrinus (A), and Ephaemi (C). ..."

113. It is recognized that the scribe of has a tendency toward scribal leaps (see p. 726 above), and Hernandez's analysis amply confirms such a tendency (see ibid., 70-74). But it is curious that the longest singular omission in Rev (20:9-10a) does not quite seem to be so explainable (ibid., 71-72, and 187 n. 92[-188]).

(- Royse, Scribal Habits (2008) p. 731)

Thus Royse confirms Hernandez' findings for the uncials, and reviews him favourably, coming to the same conclusions.

Singular Readings of

Codex Sinaiticus

Juan Hernández

Exerpt for review from:

Scribal habits and theological influences in the Apocalypse:

The Singular Readings of Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, Ephraemi (Mohr Siebeck, 2006)

By Juan Hernández

Headings have been added for clarity and navigation purposes.

Abstract

"... The singular readings are considered an important area of text-critical study because they offer us direct and unmediated access to a scribe's specific textual changes within individual MSS. Such information affords us with the most reliable text-critical data for profiling scribal copying habits and opens a window into their world.

This dissertation fills this lacuna by offering a fresh discussion of the Apocalypse's singular readings in Codex Sinaiticus (א), Alexandrinus (A), and Ephraemi (c), modeled on the respective text-critical studies of Ernest C. Colwell 1 and James R. Royse. 2

Moreover, this study also assesses the Apocalypse's singular readings in light of its reception in the early church. This study finds that the scribes of these three MSS omitted more often than they added to their texts, were prone to harmonizing, and in the case of at least one scribe, made significant theological changes to the text of the Apocalypse."

1. E.C. Colwell, "Method in Evaluating Scribal Habits", The Bible in Modern Scholarship, Ed. J.P. Hyatt (Nashville, 1965), republished in Studies in Methodology in Textual Criticism of the NT, (Eerdmans, 1969)

2. J.R. Royse, Scribal habits in early Greek NT papyri, dissertation (1981), subsequently Revised, (Brill, 2008)

Book of Revelation

Chapter 7: Summary

We began our prolegomena with the claim that the scribes of the Apocalypse (responsible for א, A, and C) were most certainly involved in addressing contemporary interpretive concerns through textual changes, though these changes occur neither where nor how nor to the degree that we might expect. As we observed in chapter six of our study, the concerns that are traditionally associated with the Apocalyse are not well represented among our singular readings. 1

Perhaps more surprising, however, has been the uncovering of singular readings that appear to reflect issues that are not ordinarily associated with the Apocalyse, such as the threat of "Arianism". The rise and influence of "Arianism" throughout the 4th century has been well documented and explored from almost every conceivable vantage point. Yet, to date no one has considered its possible influence on the text of the Apocalyse. Ancient sources on the Apocalyse do not even lead us to expect it. 2

The singular readings we have uncovered, suggest that, among other things, the threat of "Arianism" appeared to be a pressing concern for at least one scribe. Their presence in the Apocalypse raises suspicions that the influence of "Arianism" might also be felt elsewhere.

Nonetheless, the tendency to editorialize so heavily is predominantly confined to the scribal activity of Codex Sinaiticus (א). The scribes of Alexandrinus (A) and Ephraemi (C) exhibit no such tendencies. This is a reminder that we should be reluctant to generalize about what scribes ought to do. Together, the scribes of א, A, and C confound widely held assumptions and stereotypes about scribal copying practices.

One of these cherished assumptions is the belief that scribes tended to add rather than omit from their texts. Ironically, the one consistent tendency our scribes have exhibited across time and space is the tendency to omit rather than add to their texts -- a find that challenges the very foundation of the lectio brevior text-critical principle. Even here, however, we must differentiate between the copying habits of each scribe. Yet the conclusion is inescapable: these 4th and 5th century scribes of the Apocalypse were omitting far more than they added to their texts.

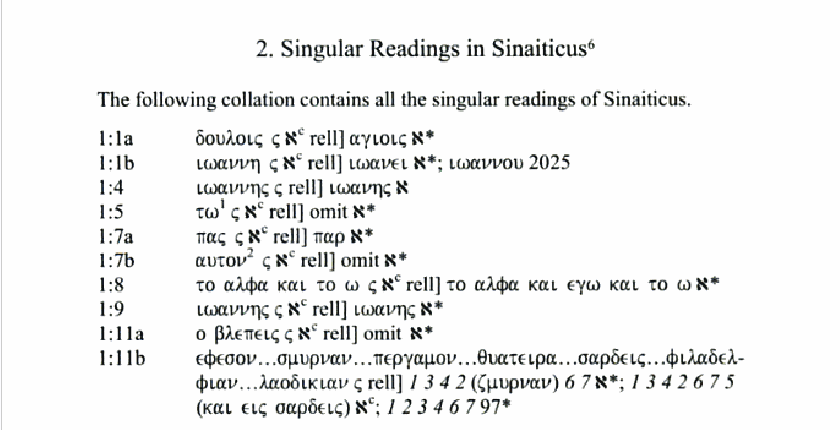

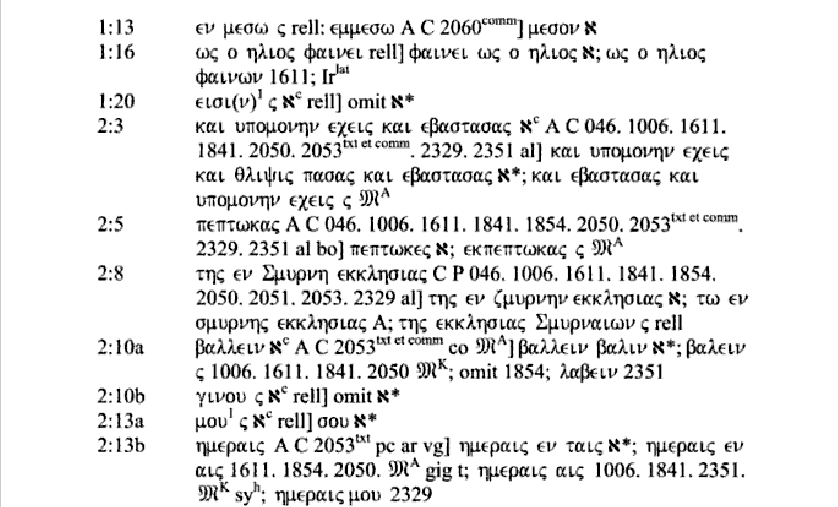

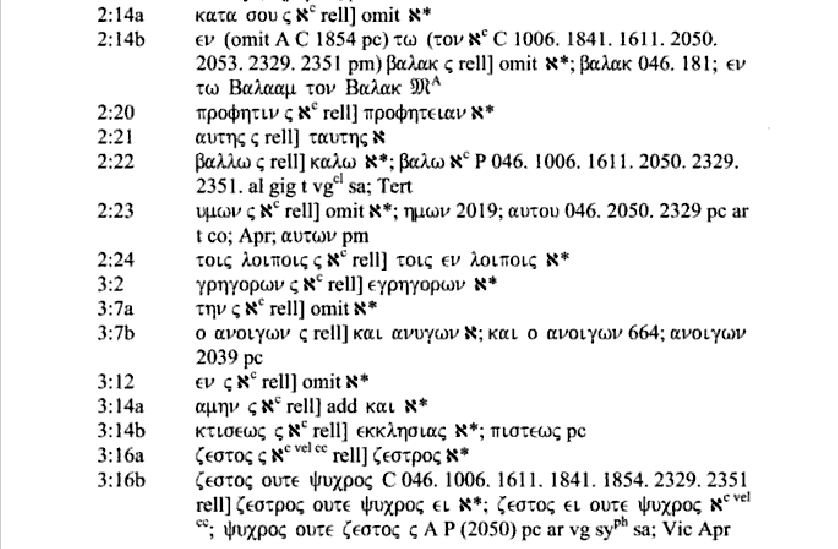

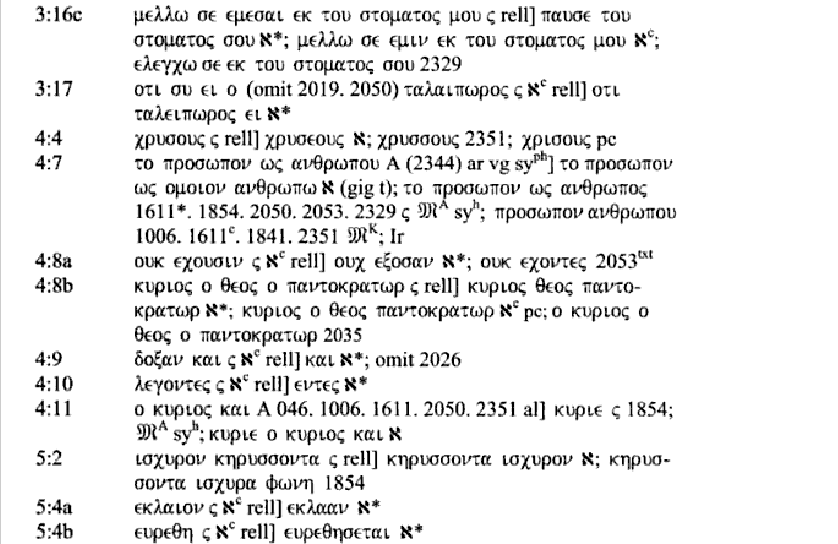

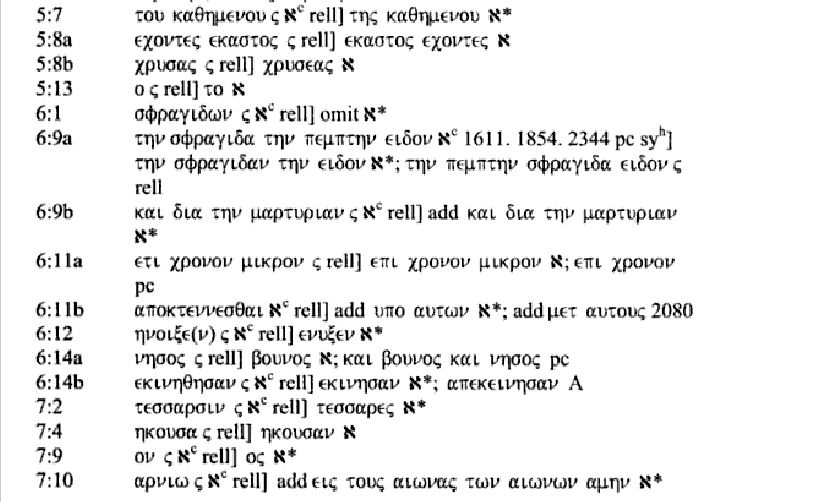

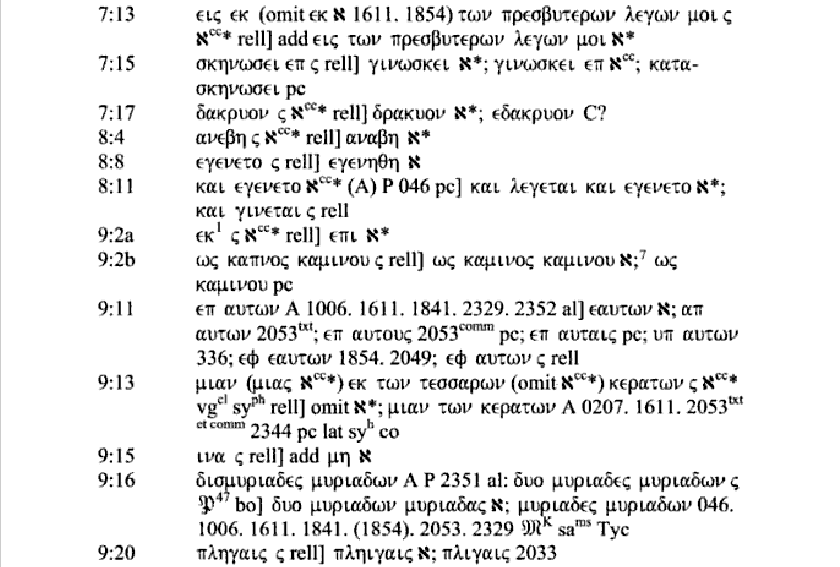

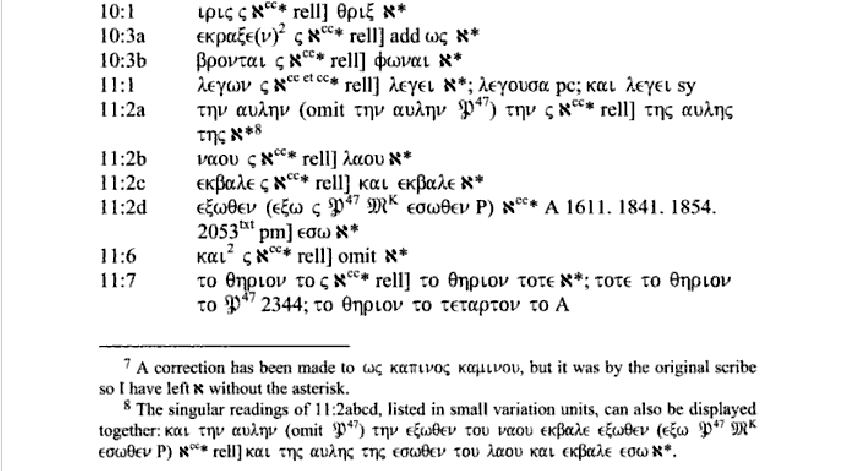

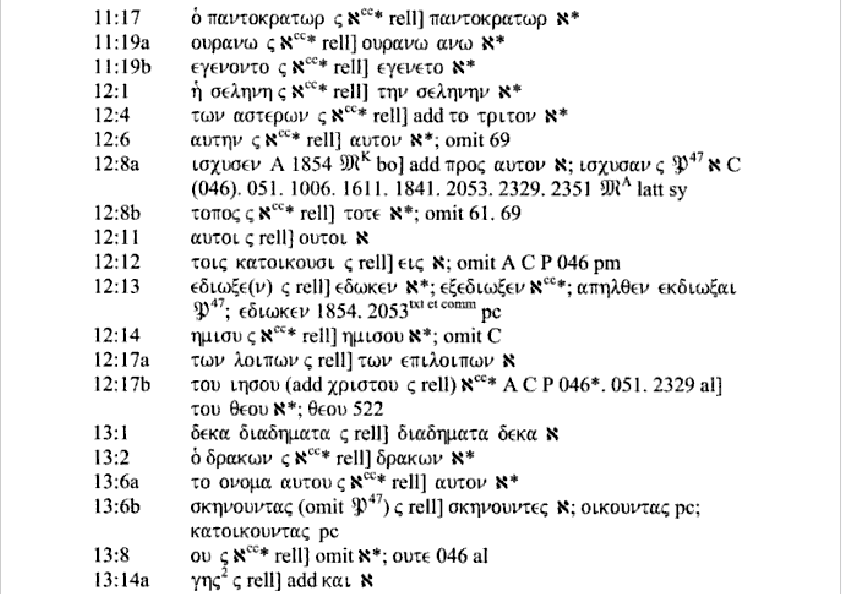

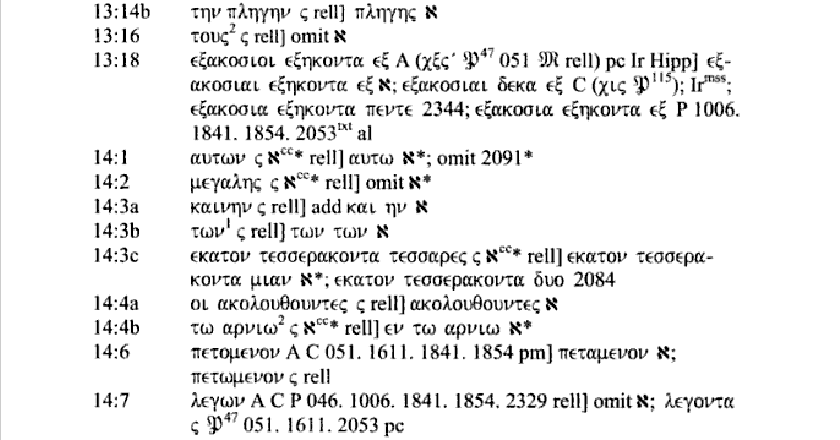

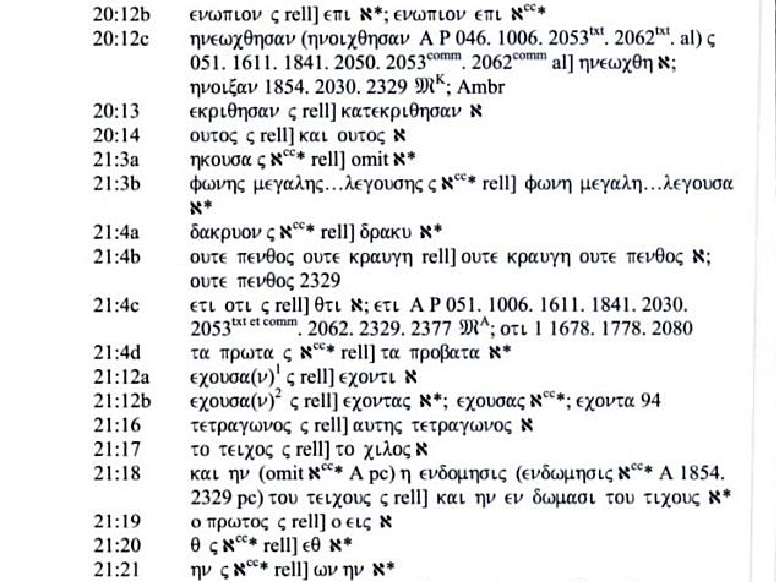

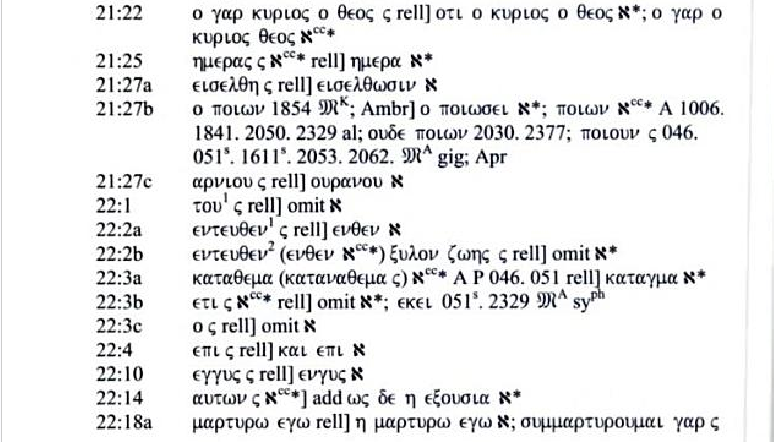

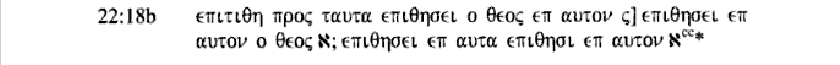

Singular Readings of א

Brackets: The first reading to the right of the bracket is א (or א*), followed by any other relevant readings with their supporting witnesses.

Note: Meaning of 'rell'

Also sometimes rel. From Latin reliqui, meaning "[the] rest." Used in Nestle-Aland (and elsewhere) to indicate that all uncited witnesses support the reading. In other editions, it may simply mean that the vast majority support the reading. Some may even use specialized notations after rell (e.g. rel pl, "most of the rest").

[Here Hernandez adds 2 more pages of singular readings,

at about 32 readings per page = +64 more, (pg. 206-207)..]

...for well over 200 singular errors by the scribe of Sinaiticus in the Book of Revelation alone.

At least 25 of these appear to be accidental omissions by the scribe (and some are undoubtedly homoeoteleuton errors).