INTRODUCTION

Saint Epiphanius of Constantia bishop of Salamis

born c. 315, near Eleutheropolis, Palestine died May 403, at sea; feast day May 12

Saint Epiphanius of Constantia, fresco at Gracanica Monastery, near Priština, Kosovo.bishop noted in the history of the early Christian church for his struggle against beliefs he considered heretical. His chief target was the teachings of Origen, a major theologian in the Eastern church whom he considered more a Greek philosopher than a Christian. Epiphanius’ own principles were discredited by the harsh nature of his attacks.

Epiphanius studied and practiced monasticism in Egypt and then returned to his native Palestine, where near Eleutheropolis he founded a monastery and became its superior. In 367 he was made bishop of Constantia (Salamis) in Cyprus. He spent the rest of his life in that post, spreading monasticism and campaigning against heretics. His orthodox views conflicted with those of the Roman emperor Valens, who governed in the East from 364 to 378 and who had embraced Arianism, but Epiphanius was protected by the veneration in which he was held for his sanctity.

In 403 Epiphanius went to Constantinople to campaign against the bishop there, St. John Chrysostom, who had been accused of sheltering four monks expelled from Alexandria for their Origenistic views. Becoming convinced of the falsity of this and related charges made by Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria (who wanted to depose John), Epiphanius set sail for Cyprus but died en route.

A zealous bishop and a revered ascetic, Epiphanius was lacking in moderation and judgment. These defects are reflected in his writings, of which the chief work is the Panarion (374–377), an account of 80 heresies and their refutations, which ends with a statement of orthodox doctrine. His Ancoratus (374) is a compendium of the teachings of the church. His works are valuable as a source for the history of theological ideas.

- Encyclopedia Brittanica

5th Century Canon List

with Pericope de Adultera

Background

Taken from: A Tidbit on the Pericope Adulterae,

by Mr. Gary S. Dykes, published online as a .PDF at:

Tidbit on PA < - - .PDF here.

A Tidbit on the Pericope Adulterae

courtesy: Mr. Gary S. Dykes

'Typically the older Alexandrian MSS omit Jn 7:53-8:11, a text known as the "Pericope Adulterae", or reposition it elsewhere.

For what its worth, I present this interesting piece of information, here, as it is often overlooked.

It concerns some papyrus fragments from Egypt, published in 1926 in:

The Monastery of Epiphanius at Thebes, Publications of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, N.Y. Walter Crum and H. E. Winlock. H. G. Evelyn-White edited these fragments in volume 2.

The fragments received more attention in 1982 in DUMBARTON OAKS PAPERS: Number Thirty-Six. IN an article by Carl Nordenfalk (pages 29-38), with full fascimiles.

These are fragments of Gospel Canon Tables! Found in/near the tomb of Daga (Between Medinet-Habu and the Valley of the Kings).

There in the 6th century Epiphanius took up residence. Found amongst his personal papers were a Gospel Book, with the Eusebian Harmony, the present fragments.

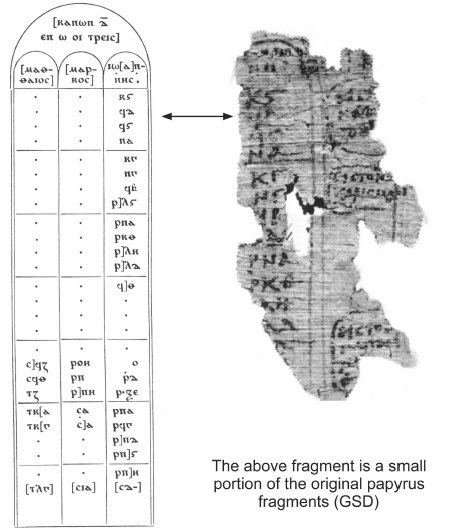

The fragments date in the 6th century or a bit earlier, possibly 450-550 A.D. It is to be noted in the small portion (reproduced below) of the 15 fragments, that in John an extra digit is added to the usual sequence. This is explained in Nordenfalk's own words:

'...all the numbers in the row for John are, from some number after 70 and before 91, one digit ahead of the normal sequence. Ther can be only one explanation. The Gospel text must have contained the pericope of the Woman Taken in Adultery (John 7:53-8:11), which was absent in the Gospel Book of Eusebius as well as in practically all the oldest codices which have been preserved. Not only was it included in our manuscript, but also, and more unusually, it was given a section number of its own, with the result that all the following sections had to be renumbered.'

For a full explanation, I suggest you see the full article in DOP, number 36, 1982. From which the above quote comes.

- Gary S. Dykes

Reconstructed Canon List & Fragment