Page Index

Last Updated: Feb 10, 2009

Section 1: - Introduction: John's Use of Mark

Anderson on Mark & John - supplements and expansion

Section 2: - John Uses Mark

Mark as a Base - Alignment of John with Mark

Mark / John Interconnections: Part I - John the Baptist etc.

Mark / John Interconnections: Part II - Jesus Feeds 5000 etc.

Conclusion - evidence for John 8:1-11

INTRODUCTION

Mark and John

'The question naturally arises whether in writing the Fourth Gospel the evangelist made use of sources as well. He knew the Synoptics (see commentary on 3:24; 11:2) but did not make extensive use of them.

Only 8% of the Synoptic material has parallels in the Fourth Gospel, and even these parallels are not close. There are indications within the text of the Fourth Gospel that the evangelist may have made use of other sources in composing his Gospel.'

- Colin Kruse

Tyndale NT Commentaries: JOHN (2003), p20

Kruse goes on to demonstrate John's reliance upon Mark and/or previous Gospel traditions:

'(on John 3:24, ) The evangelist explains parethetically that,

'This was before John was shut up in prison.

This appears to be an unnecessary comment, because there is no mention of John being put in prison in the Fourth Gospel. However, Mark 1:14 (cf. Matt 4:12) says,

'After John was put in prison, Jesus went into into Galilee,

proclaiming the good news of God.'

This implies that Jesus began His ministry after John's imprisonment (from which he did not escape). It appears that the Fourth Evangelist was aware of what Mark had written and felt the need to explain to readers of Mark's Gospel that the parallel ministry of John and Jesus occurred prior to John's imprisonment.'

- Colin Kruse,

JOHN (ibid.)

It seems clear then (contra Bultmann etc.) that cases like the mention of the Annointing in John 11:1-6 is not evidence of any dislocation or rearrangment of John's Gospel, but rather reflects John's informal reliance on the reader's prior familiarity with Gospels like Mark:

Jesus receives news of Lazarus' illness (Jn 11:1-6)

The evangelist begins,

'Now a man named lazarus was sick. He was from Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha.

This the first reference to Lazarus, and the evangelist does not expect his readers to know who he is; so he explains that he is from Bethany, the village of Martha and Mary, adding later that he is the brother of these two sisters (2-3). The evangelist presumes his readers will know who Mary and Martha are, perhaps from a reading of Luke's Gospel (Luke 10:38-42).

However, he provides further description of Mary:

'This Mary, who's brother Lazarus now lay sick, was the same one who poured perfume on the Lord and wiped His feet with her hair.

In the Fourth Gospel, the story of Mary annointing Jesus' feet comes in the next chapter (12:1-8). So people reading the Gospel for the first time would not have encountered it yet. The evangelist, therefore, assumes his readers already knew about the annointing, perhaps from oral tradition, or from parallel accounts in Mark 14:3-9 (& Matt 26:1-3).

(The parallel accounts are similar to that in the Fourth Gospel, but there are some differences: the woman is not named; she anoints Jesus' head not His feet, and the action takes place in the house of one Simon the Leper .

Luke has an account of an annointing, but in this case, it is Jesus' feet that have perfume poured over them, and his feet are wiped by the woman with her hair. In this case the woman is one who "had lived a sinful life in that town", and the annointing took place in the house of Simon the Pharisee [Luke 7:36-50].)'

- Colin Kruse,

JOHN (ibid.)

This evidence from John, combines well with three key parallel incidents:

| Incident | Mark | John |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Feeding of the 5000: | 6:30-44 | 6:1-14 |

| (2) Walking on Water | 6:45-52 * | 6:15-21 |

| (3) Triumphal Entry: | 11:1-11 | 12:12-19 |

( * The Walking on Water incident is a part of the famous Lukan Omission (Mark 6:45-8:25), and may be a singular case of 'reverse borrowing', i.e., the final redactor of Mark actually took this from John! See our previous page on this problem here:

Part VI: The Lukan Omission < - - Click here. )

Anderson on Mark and John

Paul N. Anderson's 2001 article Mark, John, and Answerability (SBL Nov.17-20 2001) provides a good up-to-date discussion of the key observations regarding the relation between the two gospels. Here we have culled some of the main highlights in point-form:

A Sketch of Forces and Exchanges

The proposed history of John begins with smaller primitive 'Gospel' that looks much like Mark. And indeed, it is supposed to act as a supplimental, complimentary, and corrective companion to Mark. In this scenario, 'Proto-John' was written just after Mark was introduced into circulation, and is based upon equally early and authentic oral and written traditions about Jesus' ministry.

On the one hand, this proposal explains well the relatively strong similarities to Mark:

The Beginning (Mk 1:1, Jn 1:1,14, 17-18)

Similar Passion Narratives including an ending with Post Resurrection appearances.

Similar beginnings with John Baptist preparing the Way.

Similar callings of Peter and Andrew and others (Mk 1:16-20 Jn 1:19-34)

Similar portrayals of Jesus as teacher and healer, and Son of Man

Similar intensification of conflict over Sabbath laws and blasphemy

Initial movement from Judaea into Galilee and back up to Jerusalem

The Way of the Cross as pattern for all followers of Jesus

Then again, there are augmentations to Mark:

(without the feeding of the 5000 and walking on water,)

five new miracles to fill out the beginning of Jesus' ministry.

Three Judaean 'Signs' broaden the ministry of Jesus.

Material from about John the Baptist fills out story,

emphasizing that John is NOT the Messiah...

The I AM sayings are added to clarify Jesus as Revealer

and the One Sent from Father Debates with Jewish leaders

expound and authenticate Jesus as Divine Messiah,

and are meant to invoke belief in Jewish readers.

Next we have the important Omissions of Markan Material.

If John really did write second, with a knowledge of Mark or at least Markan tradition, then he clearly left out significant material. At times he does indeed acknowledge the existance of, or presuppose the knowledge of facts he does not provide in his own gospel. For example,

Jesus did not Himself baptize (Jn 4:2)

Another Judas beside Iscariot exists (Jn 14:22)

John is aware of likely critiques for leaving things out,

and provides a pre-emptive response (Jn 20:30)

As well, the Passion is covered fully and appears built around Mark,

but John drops much of Mark's middle, to make room for complimentary material.

the Kingdom Parables and other teachings are missing,

but supplimented with other material.

the Markan Apocalypse (Mark 13) is missing completely

but the subject of 'future' persecution is expounded.

The Eucharist is missing, and so is Jesus' own Baptism.

The Markan Miracles (assuming chapter six is not in first edition) are missing, and others are substituted.

The Chronological (Dis)Order of Mark is Corrected and Supplimented

Earlier ministry of Jesus alongside of John Baptist is provided.

Earliest miracles are provided (Wedding and Healing)

are NOT excorcism or healing of Peter's mother-in-law.

Temple Cleansing is placed at the beginning,

and the last few years of Jesus' ministry is highlighted and fleshed out.

Head annointing is retold as a FOOT annointing.

Date of the Last Supper (or an earlier meal) is placed a day earlier,

to allow Crucifixion on Passover.

Didactic/Dialectical Changes away from Mark

The theological points and interpretations of Jesus' conflict and teaching are transposed from the time of their occurance to the time and setting of the Gospel apologists:

Roles of Elijah and Moses are fulfilled by Jesus

rather than John Baptist (John denies being either).

Parables are retired and replaced with direct teaching

about what the Kingdom of God is and is not like.

Mark's Messianic 'Secret' is reversed in John

and Jesus reveals His identity openly.

The Miracles are not responses to faith,

but Revelatory Signs that lead people to belief and Eternal life.

Apostleship is broadened to include women,

Samaritans, and others not members of the Twelve.

Conclusion

As Anderson notes, any one of these points may be debated, but together they form a plausible and widely supported picture of John the Evangelist's purpose in writing: He seeks to further Mark's work, not compete with it, but suppliment it and develop it, and correct various cumulative misunderstandings.

The evidence suggests then, that John had Mark available when composing his Gospel, and expected his readers to be familiar with it (with a very understandable exception - the Walking on Water).

Mark as a Base Outline for John

Mark and John are also similar in size and in the arrangement of their contents. And there seems to be a much stronger correspondence than would be indicated by the strictly 'parallel' material between the Synoptics and John.

At the same time, we can expect any Gospel to have a significant body of common material, with a (practically forced) standard arrangement /order (e.g. triumphal entry, passion, resurrection). And certain major events will act as a backbone against which the rest of the material is chronologically arranged.

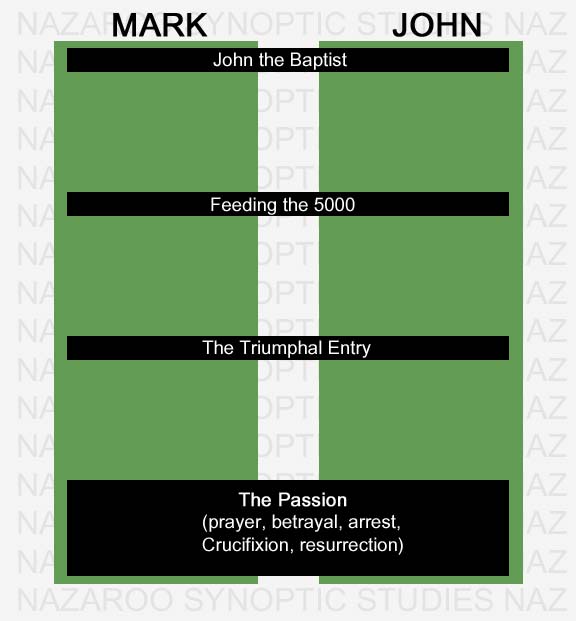

We can see this basic structural outline in the position of several key events and sequences:

Shared Backbone

Its from this shared backbone that all the other elements find their relative chronological placement and correspondence between the two Gospels, Mark and John.

Although a few items are clearly displaced (e.g. the Temple Cleansing, the Annointing etc.), most other items have a surprising correspondence and connection between the Gospels. Some sections, although displaced, are only slightly and locally rearranged. One may discover that most of these minor oddities seem to have an additional structural purpose of their own.

Before assuming that diverse material is completely unrelated, we are obligated to examine the possibility that various segments which are chronologically parallel (relative to the Gospel frameworks) are related in other more subtle ways. Three obvious relations are:

(1) that parallel but divergent material is supplementary, and expands upon the (previous) narrative/discourse with which it has been paired off.

(2) that the alternate material is complimentary in some sense or function, such as for didactic purpose or ritual use.

(3) that this material is meant to create a larger wholistic 'meta-picture' which is only partially seen in individual Gospel accounts, or is even non-existant in fragments themselves.

It is only when avenues like these are exhausted, that we should probably abandon the idea that there may be a deliberate relation between the opposing passages in each Gospel. Opening up these lines of investigation allows us to consider many ways in which the Gospels may have been composed, and designed to work together.

Mark / John

Interconnections: Part I

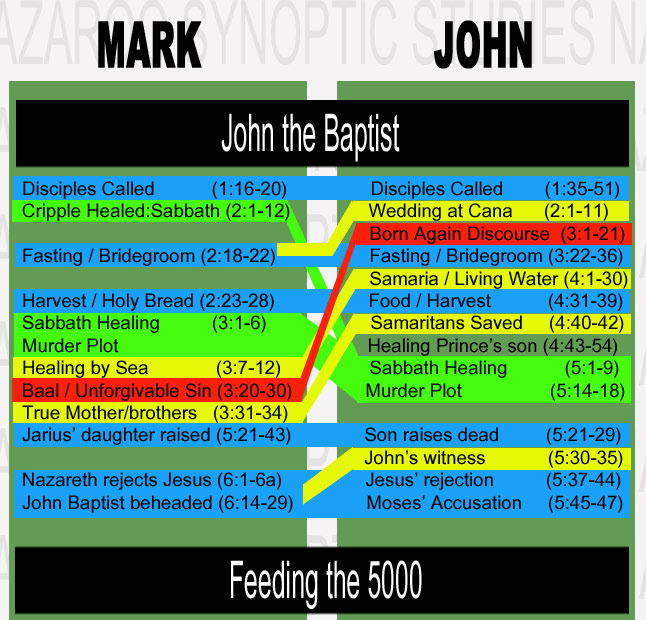

Having accepted the possibility that John for instance has used Mark as a blueprint or structural basis for his own outline, the investigation is straightforward. Let us take the first third of the Gospel(s) and see what can be plausibly connected.

Stunning Parallels

Relaxing the requirement for strict literal parallelism gives a dramatic result: It is clear that a large portion of John interconnects with Mark. But most importantly, John is clearly meant to act as a kind of commentary or 'midrash' on Mark.

Many of the once puzzling Johannine Discourses, thought by some to have been virtually made up by John, are seen to be direct verbal interpretations of physical acts in the public ministry of Jesus. Its as though while Jesus is traveling through Galilee and Samaria, he is simultaneously debating with the Judaean authorities in Jerusalem.

We can see for instance how the Third Discourse (the Son of God Discourse, Jn 5:19-47) follows closely the narrative events in Mark 5:21-6:29. Both the chronological order of events is matched by the Discourses and the thematic content also is strongly connected, emphasized, and expanded.

Perhaps some of this exchange was historically carried out in a kind of long distance 'correspondence' between representatives from Jerusalem and Jesus/John during their public activity among the Lost Tribes of the North.

John has been written not only to function as a complete Gospel in itself, but also as a detailed commentary on Mark. This is now so evident that trying to write a commentary on Mark without consulting John appears foolish.

A Door Closes

The first Third of Mark's Gospel fittingly begins and ends with John the Baptist's ministry and testimony. What is left ringing in our ears, because of details only provided by Mark is that the Herodians (Mark 3:6) were actively behind the plot to kill Jesus. We recall that Herod had appointed and controlled the 'puppet priests', and his will was behind their organized activity, supported by the powerful Pharisees.

The Herodian party had already murdered John the Baptist, and John the Baptist's indictment against them was headed by the blatant "Accusation of Moses"(Jn 5:45) against their 'king': ADULTERY (Exod. 20:14) -

"It is not lawful for you to have her." (John Baptist, in Mark 6:18).

And so this large section of the Gospel closes.

Mark / John

Interconnections: Part II

Now examining the next section, we are able to see again the same remarkable connections across both Gospels:

While some material undergoes a significant rearrangement locally, the main backbone remains full and solid, and the ADULTERY connection is glaring.

It seems quite plain that the confrontation between the Herodian religious authorities and Jesus in John's account (Jn 8:1-11) is meant to illustrate and resonate loudly with Jesus' teaching in Mark on ADULTERY and DIVORCE.

But the most powerful and remarkable feature of the whole correspondence, is that the two very difficult, almost impenetrable mysteries in John taken alone, the seemingly random "Jesus went to the Mount of Olives",(Jn 8:1) and the equally weak, almost disconnected Jn 8:12, "I am the Light of the World", suddenly jumps out at us and hits us over the head with a hammer:

John is calling to rememberance the Transfiguration on the Mount, but does not speak of it openly (he was under oath not to discuss it - Mk 9:9, but this no longer holds: yet there may be danger to parties still living in Jerusalem). Mark, writing in Rome from Peter's intimate testimony, is not under any such restriction, and happily reports the amazing event that transpired on the Mountain, including the discussion with Moses and Elijah.

Conclusion

Of course all study of Holy Scripture is a rewarding endeavour in itself.

We are content at the moment however, with revealing to the reader the remarkable evidence from the Gospel of Mark itself, as to the Authenticity of the Pericope de Adultera .

Even though we happily concede that Mark was probably written before John wrote his own Gospel, the fact that John used Mark as a base for his own supplementary historical and teaching material exposes for us the remarkable feature that John intended his story of the Woman Taken in Adultery to resonate with Mark's report.

Jesus' teaching regarding the Accusation of Moses exposed by John the Baptist against the Herodians, His teaching regarding Divorce and Adultery, is aptly contrasted with His tender mercy toward a woman caught in the middle of this epic battle between the corrupt Religious authorities of Jerusalem and the King of Kings.

Mark has become the earliest textual witness for the authenticity of John 8:1-11, being acknowledged to be the first gospel written, and penned some 150 years before the oldest known copy of any gospel.

Some may think it must end here. For how could there be an even earlier witness to the existance and authenticity of John 8:1-11?

We can only remind our brothers and sisters in Christ, that with the Lord, anything is possible. And more evidence will surely follow, since it is a task of the Holy Spirit to bring the truth of the Gospel to the light of day.