Introduction

The following brief sketch of Davidson is given by the Encyclopedia Brittanica:

SAMUEL DAVIDSON (1807-1898) - Irish biblical scholar, was born near Ballymena in Ireland . He was educated at the Royal College of Belfast, entered the Presbyterian ministry in 1835, and was appointed professor of biblical criticism at his own college.

Becoming a Congregationalist, he accepted in 1842 the chair of biblical criticism, literature and oriental languages at the Lancashire Independent College at Manchester;

But he was obliged to resign in 1857, being brought into collision with the college authorities by the publication of an introduction to the O.T. entitled The Text of the Old Testament, and the Interpretation of the Bible, written for a new edition of Horne's Introduction to the Sacred Scripture. Its liberal tendencies caused him to be accused of unsound views, and a most exhaustive report prepared by the Lancashire College committee was followed by numerous pamphlets for and against.

After his resignation a fund of 3000 pounds sterling was raised as a testimonial by his friends. In 1862 he removed to London to become scripture examiner in London University, and he spent the rest of his life in literary work . He died April 1st 1898 .

( - Volume V07, Page 864 of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica )

[Samuel Davidson is often mistakenly listed as a member of the Old Testament Revision Committee for the Revised Version of 1881. However, this confusion is due simply to his sharing the same last name with the much younger Rev. Andrew Bruce Davidson (1831-1902), D. D., Professor of Hebrew, Free Church College, Edinburgh, who actually was on that committee.]

More Details of His Life:

The following is from the book review of Davidson's autobiography (1899), written by C. F. Bradley for The American Journal of Theology, July 1900:

The life of Davidson has special interest because of his unique position among English bible critics. His autobiography, which he started at 67, devotes less than 30 pages to the first 50 years of his life. He records his birth in Kellswater Ireland, and sketch his education at home in Ballymena and Belfast.

In 1832 he was licensed to preach by the Ballymena presbytery (i.e. Presbyterian denomination), subscribing to the Westminster Confession "with exceptions". He writes,

"But my mind was in traditional fetters at the time."...

After two years of preaching he was appointed professor of biblical criticism to the students under the care of the general synod of Ulster. He published lectures on biblical criticism in 1939.

Failing to secure the professorship of Hebrew in Glasgow College, and finding his mind turning toward Congregationalism, he was in 1842 appointed professor of biblical criticism in the Lancashire Independent College at Manchester. Of his work on Sacred Hermeneutics (1843), he says,

"Sufficiently orthodox, the book was well received by the public."

In 1844 Davidson visited Germany for the first time, and met Neander, Bleek, Roediger, Tholuck, and Bretschneider. In four years he released the 1st volume of his Introduction to the New Testament (1848), which secured him the degree of doctor of theology from the University of Halle.

His fame and influence seemed to be rapidly extending until the publication of his volume on the O.T. for the new edition of Horne's Introduction, The Text of the Old Testament and the Interpretation of the Bible (1857)*. He says,

"This led to our being turned out of house and home, with a name tainted and maligned."

The story of his resignation is told by Mr. Picton, one of his old students. His daughter in the preface to his autobiography said that,

"his attitude was one of serene detachment, and though he spoke plainly on that as on most other things and considered that he had been treated very unjustly, he shrank from recording the story himself. "

At 86 however, he wrote, regarding ecclesiastical trials in America,

"A committee appointed to discover heresy will generally succeed in doing so... It is said that heresy trials are mere farces, but they are not so to him who is declared heretical; for the brand is remembered against him, meeting him at every step in all the relations of life. The 'proper' outcome of a heresy trial is the gallows or the stake."

This is proof that the iron had entered his soul.

The process by which he changed from conservative and traditional views to those of radical criticism little or nothing is said. That the change was due to German, and especially the Tubingen, school of criticism is perfectly evident. But one would like to know something of the psychological process and spiritual experiences which belonged to one of the most rapid and complete revolutions known to theological biography.

Of any internal struggle or sense of loss or fear of consequences to the church there is little or no trace. There is instead a great confidence in the new views, and a religious faith which apparently remained steadfast and serene as it grew increasingly vague and lost its early supports. Henceforth Davidson is the solitary scholar, working on with placid patience and untiring industry, writing, revising, and publishing. One might imagine him to be a German professor stranded in England.

He established a quiet home in London, ..."but belonging to no outward church or sect, an eclectic and peculiar", with little personal influence or following, unchecked by the responsibilities of teaching, and unsupported by membership in a great communion and the intimacy of strong men associated in a great work. The contrast between this life and that of Hort (one of his avid fans) is most striking. Davidson's solitariness is deeply pathetic. This is doubtless due in large measure to his wide departure from his early faith.

But he continued to believe in a loving Father, in Jesus Christ his son, the highest, purest likeness of God in humanity, and in the Holy Ghost, the divine influence diffused through creation, dwelling in all believers, sustaining and pervading their life. "The steady contemplation of Jesus by the disciple is the instrument of renovation."

His comments are those of ... a learned and conscientious scholar, an idealist, and a lover of peace, of truth, of God, and of his fellow-men. It is easy to imagine him as far happier and more influential as a professor in a German university; or saved from extreme negative views by a responsible position in the Anglican Church [as was Hort's compromising choice].

He would in either case have been a more potent factor in the religious world and less exclusively a mere man of books. Yet in either case we should have lost the shining example of this brave and solitary scholar whose spirit excommunication could not embitter and whose religious faith, passing through many transformations, survived them all."

(C.F. Bradley, A Review of Autobiography and Diary of S. Davidson (1899), from The American Journal of Theology, Vol. 4 No.3 (Jul 1900), pp 621-623)

If Samuel Davidson (1848) was the door by which German criticism entered the English speaking world, and misled a whole generation, we may ask what happened to Davidson:

And the answer is frightening, but not wholly surprising. Davidson began as a Presbyterian, and ended up a vague, semi-apostate Christian, unsure of any orthodox doctrine shared by Protestant or Catholic.

After having shipwrecked the faith of thousands, it was natural (and as the Alcoholics Anonymous say, 'enabling' and 'co-dependant') that Davidson himself would fall away, never perhaps completely, but never to really return either.

Like so many scholars who valued scholarship higher than the Christian faith itself, Davidson ended up in a kind of agnostic purgatory of his own making.

When Davidson brought out his Introduction to the New Testament in 1848, the English public was largely unaware of what they were buying into. It had all the appearance of good 'scholarship'. He was hailed as someone bringing in the latest discovery from Germany.

Ten years later however, the English Christians were well prepared for Davidson's imports. When he released a similar 'Introduction' for the Old Testament, they took a harder look at the content, and nailed him as a heretic and apostate.

Perhaps its ironic that Davidson's NT experiment was not so branded, because in the long run, it did by far the most damage to Christianity in the English world.

But in a way this too could have been predicted. Presbyterianism and Protestantism in general has been caricatured as little more than 'pork-eating' Judaism. While this is an exaggeration, it is plain that there is a strong 'legalism' / law-and-order streak running deep within Protestantism.

And it was natural that among many Protestants, Davidson could attack orthodox Christian (New Testament) doctrine and text with impunity, since Protestants were suspicious of Christian tradition as 'popery'.

But when Davidson attacked the Old Testament, he was attacking something very dear to the heart of many conservative Protestants, and they would have none of it. He was lucky not to have been drawn and quartered in Scotland, even in 1850.

This too is ironic, for Christianity is largely founded upon the Light of the New Testament, not the Old. Davidson should have been stopped in his tracks with his first book. In that work lay the seeds of destruction for an entire generation of English Christians.

Attacking the Old Testament in the end had little impact upon Christianity by comparison.

Davidson and Dr. Hort

There is good reason to believe that Davidson's work, especially his Introduction to the New Testament, had a deep and lasting impact upon F.J.A. Hort, who would later so drastically alter that Greek text of the NT.

Yet Hort also must have been deeply affected by the results of Davidson's open apostacy and 'excommunication' upon his subsequent career. Hort must have taken these lessons especially to heart, and appears to have been concerned about being branded a heretic for his views throughout his life.

It is no surprise then that Hort approached his own career quite differently and cleverly. Hort always kept his radical and heretical viewpoints quite secret, only expressing himself in private letters to his trusted friends such as Westcott and Lightfoot.

Hort then used the conservative cloak of the Anglican clergy as a shield and base to launch his own innovations. For Hort, hiding in the skirts of the mother church was a key component to the success of his agenda to undermine the orthodoxy of his day.

Yet the scope of Hort's damage was more limited than he would have wished. In fact, predictably, Hort really had only affected a semi-apostate academic core within English protestantism. Those who heard Hort were those who already wanted to hear, and who came into direct contact with his sphere of influence.

Many Christian groups, both Catholic and Protestant were forever outside of Hort's reach, and only fellow academics were in any real danger of falling into his web, and possibly too weak minded to struggle out of it.

Principle Works:

Sacred Hermeneutics Developed and Applied (1843), rewritten and republished as

A Treatise on Biblical Criticism (1852),

Lectures on Ecclesiastical Polity (1848),

An Introduction to the New Testament (1848/1851)*,

The Hebrew Text of the Old Testament Revised (1855),

The Text of the Old Testament and the Interpretation of the Bible (1857)*

Introduction to the Old Testament (1862),

On a Fresh Revision of the Old Testament (1873),

Canon of the Bible (1877),

The Doctrine of Last Things in the New Testament (1883),

besides translations of the New Testament from Von Tischendorf's text,

Gieseler's Ecclesiastical History (1846) and

Furst's Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon.

Textual Evidence

Davidson: (pg 356-359)

"Another portion of the fourth Gospel, whose authenticity has been questioned, is chapter 7:53-8:11. The paragraph has given rise to strong suspicion. Many have denied that it was written by the author of the Gospel, or by John the Apostle. 1 It is found, in many ancient authorities, and is defended by numerous critics.

Textual Evidence For Authenticity 2

i. It is contained in upwards of 200 MSS., among which are the uncial D, G, H, K, M, U. Jerome too says that it was found in any Greek and Latin MSS, while some scholiasts appeal to its existance in ancient copies (arcaia antigrafa). 3

Of versions, it is in the Arabic, Persian, Coptic, AEthiopic, in MSS of the Philoxenian Syriac, the Syriac of Jerusalem, Slavonic, Anglo-Saxon, in most MSS of the old Italic, the Vulgate, the Apostolic Constitutions.

It is also quoted by Jerome, Ambrose, Augustine, Sedulius, Leo, Chrysologus, Cassiodorus, the author of the Synopsis Sacrae Scripturae, and by Euthymius as "an addition to the Gospel not without use". 4

Textual Evidence Against Authenticity 5

ii. On the other hand, it is wanting in B, C, L, T, X, Delta, in about 50 written in the cursive character, and 30 evangelistaria. Probably too A wanted it, for the two leaves of the codex here deficient in that MS would not have been sufficient to contain the 12 verses with the other portion. It should also be remarked, that C is defective from 6:50 to 8:12. In L, the empty space left is not large enough to contain the whole piece. In Delta there is also a gap. 6

The verses are marked with an obelus in S, and in about 30 MSS. They are asterisked in E and 14 MSS. 7 Eight codices and one evangelistarium put them at the end of the Gospel. Others place a part of them there; viz., from 8:3-11. 8 Others have them at the end of the 21st chapter of Luke; and others at the end of John 7:36. 9 The scholion of cod. i. observes, that the portion is wanting in most ancient codices (pleista antigrafa); while Euthymius says, that it is not found in the most accurate, or is marked with obeli. 10

It is not in the oldest MSS and the editions of the Peshitto; for it is certain that it was first rendered into Syrian in the 6th century. The MSS of the Philoxenian that have it, exhibit it partly in the margin; if in the text, very often with the remark that it is not found in all copies. Most MSS of the Coptic have it not. In the Sahidic, in codices of the Armenian, in the Gothic etc., it is not found. 11

Nor is it mentioned by Origen, Apollinaris, Theodore of Mopsuestia, Cyril of Alexandria, Crysostom, Basil, Tertullian, Cyprian, Juveneus, Cosmas, Nonnus, Theophylact, etc. 12

Evaluation of the Textual Evidence

From this summary it will be seen, that D is the oldest codex possessing the paragraph, though certainly in a peculiar form unlike that of the received text. 13 But the MS is not free from apocryphal additions, especially in Matthew 20:28, and Luke 6:5. 14 The fact of the paragraph's absence from B and probably A far outweighs its appearance in D. 15 It is very remarkable too, that so many MSS having it, affix marks of rejection or interpolation; while the various positions it has been forced to occupy, confirm the suspicions entertained against it. 16

The fact, moreover, of its being wanting in the old Syriac, is strong testimony against its authenticity. 17

It must be allowed, that Origen's silence regarding it is unimportant, because he had no occasion to mention it when commenting on (John) 8:22. 18

But the silence of Cyprian and Tertullian is weighty, because both wrote on subjects in which the account would have been peculiarly appropriate. 19

With regard to the latter, Granville Penn thus forcibly reasons:

"That the passage was wholly unknown to Tertullian, at the end of the 2nd century, is manifest in his book, 'De Pudicitia'. The bishop of Rome had issued an edict, granting pardon to the crime of adultery, on repentance. This new assumption of power fired the indignation of Tertullian, who thus apostrophised him:

'Audio edictum esse propositum, et quidem peremptorium, 'Pontifex scilicet Maximus, episcopus episcoporum dicit: Ego et moechiae et fornicationis delicta, poenitentia functis, dimitto" (c.1.)

- "I hear that there has even been an edict set forth, and a peremptory one too. The Pontifex Maximus -that is, the bishop of bishops -issues an edict: 'I remit, to such as have discharged (the requirements of) repentance, the sins both of adultery and of fornication.' "He then breaks out in terms of the highest reprobation against that invasion of the divine prerogative; and (c.6) thus challenges:

"Si ostendas de quibus patrociniis exemplorum praeceptorumque coelestium, soli moechiae, et inea fornicationi quoque, januam poenitentiae expandas, ad hanc jam lineam dimicabit nostra congressio."

- "If thou canst shew me by what authority of heavenly examples or precepts thou openest a door for penitence to adultery alone, and therein to fornication, our controversy shall be disputed on that ground."And he concludes with asserting,

"Quaecunque auctoritas, quaccunque ratio moecho et fornicatori pacem ecclesiasticam reddit, eadem debebit et homicidae et idolatriae poenitentibus subvenire."

- "Whatever authority, whatever consideration restores the peace of the church to the adulterer and fornicator, ought to come to the relief of those who repent of murder or idolatry."It is manifest, therefore, that the copies of St. John with which Tertullian was acquainted, did not contain the "exemplum coeleste" - the "divine example" devised in the story of the "woman taken in adultery." k

(Granville Penn, Annotations to the Book of the New Covenant, pp. 267, 268)

Much of the suspicion which naturally lies against the passage, would be removed if Augustine's method of accounting for its omission could be rendered probable:

"Nonnulli moicae, velpotius inimici verae fidei, credo, metuentes peccandi impunitatem dari mulieribus suis, illud, quod de adulterae indulgentia dominus fecit, auferrent de codicibus suis, quasi permissionem peccandi tribuerit, qui dixit: deinceps noli peccare."

- "Some of little faith, or rather enemies of the true fraith, I suppose from a fear lest their wives should gain impunity in sin, removed from their MSS the Lord's act of indulgence to the adulteress."(Augustine, De adulterinis conjugus, ii.7) l

Nicon 20 states a similar reason which the Armenians may have had for excluding the passage. m

So also Ambrose 21 remarks:

Profecto si quis ea auribus otiosis accipiat, erroris incentivium incurrit." n

It is observable, however, that Augustine does not say the paragraph was really ejected from Greek MSS for the reason he assigns. He merely conjectures, that some persons of weak faith, or rather enemies of the true faith, might have expunged it from their copies through fear of giving encouragement to sin. The father speaks of the feeling regarding the passage in the minds of some contemporaries; but that he describes the original cause of its rejection, or that he had the means of knowing it, cannot be maintained. 22

It is quite impossible, also, that this reason could have operated uniformly, both among the Greeks and Latins. Critical reasons may have led to its rejection, as well as doctrinal ones. It cannot be shewn, that the latter induced its expulsion from a single copy. 23 The only circumstance favourable to Augustine's conjecture is the fact that several copies omit no more than verses 3-11, beginning to reject where the matter seemed questionable. 24

In regard to Chrysostom, Matthaei has laboured to account for his silence on the suppostion of his acquaintance with the paragraph; but his arguments are overthrown by Lucke. Whatever may be said in favour of the pious orator thinking it unadvisable to expound the story before a voluptuous people, he was not so timid as Matthaei represents him. The paragraph must have been read before the people, both before and after Chrysostom's time. It is found in many evangelistaria; and we know that it was publicly read on certain festivals. 25

On the whole, it cannot be shewn that the greek church had it in their MSS before the fifth century; or that the Latin church had it before the fourth. It came from the West into the East not earlier than the fifth century. 26

There are readings of it which differ considerably from one another. Surely this circumstance is unfavourable to the genuineness of it; for no authentic passage in John presents an approximation to so many variations and different readings. Griesbach gives the three texts, of which that in D is the oldest. 27

On reviewing the external evidence for and against the paragraph, we believe that the latter predominates; and so furnishes a reason for entertaining suspicions of its spurious character. 28

If the authorities be not decisive of the question, they are of considerable weight, at least in conducting to a determination adverse to the passage. Lachmann expunges it from the text." 29

(Davidson, Introduction pg 356-358) 30

Davidson's Original Footnotes:

k. from: Annotations to the Book of the New Covenant, pp 267,268.

l. from: De adulterinis conjugiis, ii.7.

m. See Cotelerii Patres apostolici, vol. i. p.238, ed altera Clerici.

n. From: Apologia Davidis posterior, c. 1.

Footnotes

1. With expressions like "strong suspicion" and "many have denied", Davidson gives the impression of an army of serious scholars holding a negative opinion. In fact, in 1848, only one editor of a critical Greek New Testament had committed to a removal of the passage, Lachmann (1842).

Before this, Griesbach (NT 1774, 2nd ed.1796) had already organized the MSS into three basic groups or 'text-types', Western, Alexandrian, and Byzantine, according to the picture given by St. Jerome, and previously proposed by Bengel and Semler. He characterized these as 'recensions' (formal editions) of equal weight, and opted for a 2/3 voting system by text-type. Scholz continued Griesbach's work, but counted Western and Alexandrian as one 'text-type', failing to find a clear difference between them. In this, both Scrivener and Tregelles later agreed with Scholz:

"The untenable point of Griesbach's system, even supposing it had historical basis, was the impossibility of drawing an actual line of distinction between his Alexandrian and Western 'recensions'." - Tregelles, Printed Text, 1852 p91

"...it seems vain to distinguish it (the Western text) by any broad line of demarcation." - Scrivener, Plain Intro., 1896 p475

Lachmann had elaborated on Griesbach's approach: His first principle was to discard the readings of the 'Received Text' (traditional text), as in his opinion this text was only two centuries old. (cf. E. Miller, Guide to TC of NT, 1886 pg 20-21). He felt that the traditional text conflicted with 'better authorities'. His main object was to restore the 'text of the 4th century', which he supposed had been lost. For this purpose he laid aside all MSS except a few older ones (A, B, C, D), the Old Latin, and a few early fathers (Irenaeus, Cyprian, Origen, Lucifer, and Hilary). But only codex B (Vaticanus) was actually 4th century, and this was known only through inaccurate hand-collations.

Lachmann perhaps typifies the whole 19th century period of Textual Criticism, which is rightfully seen as the 'infancy' of the science. In this era, critic after critic attempted the impossible, by cutting corners, or by applying naive notions now known to be absurd, and prematurely publishing their 'results'. This era culminated in the notoriously flawed work of Westcott and Hort, which truly synthesized all that was supposed have been accomplished by the 1880's.

In Davidson's time however, Lachmann was seen as the 'latest research from Germany', and Davidson felt he was doing the English a great favour in bringing 19th century German 'scholarship' to his fellow countrymen. Here he hopes to convince the reader of the weight of the evidence and scholarship behind his position. He has of course already adopted Lachmann's rejection of the verses as a later addition to John.

We are best understanding Davidson's remarks about 'strong suspicion', and 'the many' that have denied Johannine authorship, as simply referencing what was in the air in Germany in the 1840's under the influence of early 'higher criticism'. Then his statement is truthful enough, and in harmony with his finishing note that the passage was also simultaneously 'defended by numerous critics' at this same time (1840-1850).

But this floating opinion does not reflect any ground-breaking scholarship so much as over-exhuberant German skepticism. This was itself a backlash from the puritanical Protestant authoritarianism which was breaking down under the pressure of the new 'scientific enlightenment', along with other radical trends and forces.

2. This appears to be a reasonable statement of the evidence as it was known at that time (1848). However, even here, Davidson is downplaying the weight and significance of portions of the evidence.

For instance, the casual reader would not pick up the true significance and power of St. Jerome's testimony, without also knowing that:

Jerome lived from about 340 to 420 A.D.,

He was personal secretary to the Bishop of Rome,

He had mastered Greek, Hebrew and Latin, and was a classical scholar, and probably the greatest textual critic of his era.

He was the chief translator of the Latin Vulgate, now used by the Latin church for ten centuries.

Nor might one immediately grasp the importance of Jerome's testimony about manuscripts that were ancient in his own time (circa 370 A.D.):

"...in the Gospel according to John in many manuscripts, both Greek and Latin, ( 'in multis et Graecis et Latinis codicibus' ) is found the story of the adulterous woman who was accused before the Lord."

( - St. Jerome, See Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus, Series Latina, vol. 23, col. 579)

One might also miss out on the fact that Jerome had specifically searched out the most ancient and reliable MSS he could find for his translation (cf. his preface to the Gospels etc.), avoiding entirely the three major Greek versions then available.

Its also of note that although he was thoroughly skeptical of possible additions to the text generally, Jerome held with absolute certainty to the authenticity of John 8:1-11, and included it without hesitation in his Latin translation.

3. What Davidson means here is that some manuscripts mark the passage with a 'scholia' or marginal note, attesting to it being found in ancient copies. Unfortunately, Davidson is not specific as to the variations in the notes, how many there are, or in what manuscripts they are found. Nor is this information easily found elsewhere. In fact, the only detailed information will be found in Scrivener:

Marked Manuscripts

The passage is noted by an asterisk or obelus or other mark in Codd. MS, 4, 8, 14, 18, 24, 34 (with an explanatory note), 35, 83, 109, 125, 141, 148 (secunda manu), 156, 161, 166, 167, 178, 179, 189, 196, 198,201, 202, 219, 226, 230, 231 (secunda manu), 241, 246, 271, 274, 277, 284 ?, 285, 338, 348, 360, 361, 363, 376, 391 (secunda manu), 394, 407, 408, 413 (a row of commas), 422, 436, 518 (secunda manu), 534, 542, 549, 568, 575, 600. There are thus noted vers. 2-11 in E, 606: vers. 3-11 in Π (hait ver. 6), 128, 137, 147: vers 4-11 in 212 (with unique rubrical directions) and 355: with explanatory scholia appended in 164, 215, 262 3 (sixty-one cursives).

Speaking generally, copies which contain a commentary omit the paragraph, but Codd. 59-66, 503, 526, 536 are exceptions to this practice.

Manuscripts Including John 7:53-8:11

Scholz, who has taken unusual pains in the examination of this question, enumerates 290 cursives, others since his time forty-one more [i.e. 331 manuscripts], which contain the paragraph with no trace of suspicion, as do the uncials D F (partly defective) G H K U Γ (with a hiatus after στησαντες αυτην ver. 3): to which add Cod. 736 (see addenda) and the recovered Cod. 64, for which Mill on ver. 2 cited Cod. 63 in error.

Cod. 145 has it only secunda manu [i.e., written 'by a secondary (unknown) hand'], with a note that from ch. viii. 3 [onward to verse 11],

τουτο το κεφαλαιον εν πολλοις αντιγραφοις ου κειται

.

[transl.: "this section in many copies is not found"]

The obelized Cod. 422 at the same place has in the margin by a more recent hand

εν τησιν αντιγραφης ουτως

.

["...in some copies (it is) thus."]

The Farrar Group etc.

Codd. 1, 19, 20, 129, 135, 207 4, 215, 301, 347, 478, 604, 629, Evst. 86 contain the whole pericope at the end of the Gospel. Of these, Cod 1 in a scholium pleads its absence -

ως εν τοις πλειοσιν αντιγραφοις

["as in many ancient copies" ]

from (of) the commentaries of Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria, and Theodore of Mopsuestia;

While 135, 301 confess they found it ...

εν αρχαιοις αντιγραφοις

["in (the) ancient copies"] :

Codd. 20, 215, 559 are obelized at the end of the section, and have a scholium which runs in the text;

τα ωβελισμενα, κειμενα δε εις το τελος, εκ τωνδε ωδε την ακολουθιαν εχει

, and on the back of the last leaf of both copies

το υπερβατον το οπισθεν ζητουμενον

.

Scrivener's Original Footnotes:

3. The kindred copies Codd. L, 215 (20 has an asterisk only against the place), 262, &c., have the following scholium at ch vii 53:

"τα ωβελισμενα εν τισιν αντιγραφοις οι κειται, ουδε Απολλιναριω. εν δε τοις αρχαιοις κειηται μνημονευουσιν της περικοφης ταυς και οι αποστολοι, εν αις εξεθεντο διαταξεσιν εις οικοδμην της εκκλησιας "

The reference is to the Apostolic Constitutions (ii.24. 4) as Tischendorf perceives.

4. Yet so that the first hand of Cod. 207 recognizes it in the text, but setting in the margin,

"

το δε λοιπον ζητει εις το τελος του βιβλιου"

( - Burgon, Guardian, Oct 1, 1873)

(Scrivener, Plain Introduction, 1896,vol. II pg 365-366)

(Scrivener is using an older system of manuscript numberings. These can be matched to modern numbers using the UBS/NA27 Introduction.)

4. The reference to Euthymius here exposes the problem facing all overly simple schemes for categorizing evidence. Much of the evidence cannot fit neatly into either a 'for', or 'against' authenticity category, nor is it easily weighted for its significance.

Since Euthymius doesn't unambiguously belong in either category, so Davidson places him in both. But not only is Euthymius ambiguous (see the 2nd half of his quote under 'against'), his evidence has little credibility, since he is talking through his hat in the 12th century A.D. As Hort has more accurately noted:

"Euthymius Zygadenus (Cent.12) comments on the Section as 'not destitute of use'; but in an apologetic tone, stating that "the accurate copies" either omit or obelise it, and that it appears to be an interpolation ( παρεγγραπτα και προσθηκη ), as is shown by the absence of any notice of it by Chrysostom."

(Hort, Introduction, Notes on Select Readings, pg 83)

Although Hort also passes over Euthymius without comment, this is hardly adequate. Not only is he a late witness, but Euthymius completely undermines his own credibility while speaking. For the absence of notice of the passage in Chrysostom (early 5th century) cannot have any bearing on the authenticity of the passage. If it was added, this must have occurred long before Chrysostom. Euthymius' evaluation of Chrysostom is offbase.

At best, Chrysostom's silence would only have indicated Chrysostom's own opinion concerning the passage, long after others such as Ambrose, Jerome, and Augustine had testified to its popularity and authenticity.

But such church commentaries cannot discuss a scripture that is not even actually read publicly at the service. In the Greek Lectionary system, our passage was deliberately skipped over, and read later on the feast days of obscure saints. The ancient church commentaries were used at a completely different time of the year.

The Lectionary tradition and practice most plausibly accounts both for the absence, and the cause of the absence of any discussion of these verses in the public commentaries.

5. Although we have added the Headings to each section for clarity, they are fully justified by both Davidson's original numbering of the two sections, and his choice of content in each. His introductory phrase, "on the other hand,.." removes all doubt about his intent in the groupings of textual evidence, i.e., 'for' and 'against'.

Here again, however, we must immediately remove some confusion, or at least clarify the issues regarding the evidence. In fact there are several key questions to be answered , and there is a difference in the very nature of the evidence germaine to each question.

(1) The Evidence for the Earliest Existance of the Passage

(2) The Evidence for the Subsequent History of the Passage

(3) The Evidence for the Authenticity/Authorship of the Passage

Dean John Burgon seems to have been the first to clearly articulate these distinctions, in discussing this very passage:

"And let me not be told that I am hereby setting up the Lectionary as the true standard of appeal for the text of the NT; still less let me be suspected of charging on the collective body of the faithful whatever irregularities are discoverable in the codices which were employed for the public reading of Scripture. Such a suspicion could only be entertained by one who has failed to apprehend the precise point just now under consideration. We are not examining the text of John 7:53-8:11. We are only discussing whether those 12 verses en bloc are to be regarded as an integral part of the Fourth Gospel, or as a spurious accretion to it."

(Burgon, Pericope de Adultera (1886), reprinted in Counterfeit or Genuine?,1978 Ed. D.O. Fuller, pg 154)

6. Here the irony should not escape the reader: What is alleged to be the strongest textual evidence against the passage is also the most blatant evidence in favour of its early existance. Its lack in seven of the oldest manuscripts is accompanied by the acknowledgement in these same manuscripts of its obvious existance and popularity. The very same hand that drops the verses in 5 out of 7 cases also leaves no doubt of its existance, nor do these scribes attempt to hide the fact of the omission.

It may be true that Codex A (Alexandrinus) likely omitted the verses, it is probably equally true that Alexandrinus had at least some strange extra space in this place:

"I proceed to offer a few words containing Codex A.

Woide, the learned and accurate editor of the Codex Alexandrinus, remarked (in 1785) "Historia adulterae videtur in hoc codice defuisse." But this modest inference of his has been represented as an ascertained fact by subsequent critics. Tischendorf announces it as "certissimum."

Let me be allowed to investigate the problem for myself. Woide's calculation (which has passed unchallenged for nearly a hundred years, and on the strength of which it is nowadays assumed that Codex A must have exactly resembled Codices  and B in omitting the Pericope de Adultera) was far too roughly made to be of any critical use.

and B in omitting the Pericope de Adultera) was far too roughly made to be of any critical use.

Two leaves of Codex A have been here lost, namely, from the word katabainon in 6:50 to the word legeiV in 8:52: a lacuna (as I find by counting the letters in a copy of the ordinary text) of as nearly as possible 8,805 letters, allowing for contractions and of course not reckoning St. John 7:53-8:11.

Now in order to estimate fairly how many letters the two lost leaves actually contained, I have inquired for the sums of the letters on the leaves immediately preceding and succeeding the hiatus; and I find them to be respectively, 4,337 and 4,303: a total of 8,640 letters. But this, it will be seen is insufficient by 165 letters, or eight lines, for the assumed contents of these two missing leaves.

Are we then to suppose that one leaf exhibited somewhere a blank space equivalent to eight lines? Impossible, I answer. There existed, on the contrary, a considerable redundancy of matter in at least the second of those two lost leaves. This is proved by the circumstance that the first column on the next ensuing leaf exhibits the unique phenomenon of being encumbered, at its summit, by two very long lines (containing together fifty-eight letters), for which evidently no room could be found on the page which immediately preceded!

But why should there have been any redundancy of matter at all? Something extraordinary must have produced it. What if the Pericope de Adultera, without being actually inserted in full, was recognized by Codex A? What if the scribe had proceeded as far as the fourth word of St. John 8:3 and then had suddenly checked himself? We cannot tell what appearance St. John 7:53-8:11 presented in Codex A, simply because the entire leaf which should have contained it is lost. Enough however has been said already to prove that it is incorrect and unfair to throw  , A, B into one and the same category, with a 'certissimum' as Tischendorf does.

, A, B into one and the same category, with a 'certissimum' as Tischendorf does.

As for L and Delta, they exhibit a vacant space after St. John 7:52, which testified to the consciousness of the copyists that they were leaving out something. These are therefore witnesses for - not witnesses against - passage under discussion. X being a commentary on the Gospel as it was read in church, of course leaves the passage out. The only uncial MSS therefore which simply leave out the Pericope are the three following:  , B, T. The degree of attention to which such an amount of evidence is entitled has already been proved to be wondrous small."

, B, T. The degree of attention to which such an amount of evidence is entitled has already been proved to be wondrous small."

(Burgon, The Pericope de Adultera, Ed. Fuller, pg 142-144)

W. Willker (2005) has dismissed Burgon's careful calculations with the following counter-argument:

"A has a lacuna 6:50-8:52a (Tregelles noted the omission). It is certain that A did not contain the PA. I have made a reconstruction of this from Robinson's Byz text with nomina sacra [the common contractions]. It fits the space exactly (+ 1,5 lines) taking into account the following phenomenon: Some people noted 1 that at the beginning of the first existing folio two extra lines in slightly smaller letters have been added and speculated about its implications for the contents of the lost folios. But there is a simple explanation: A* omitted Jo 8:52 due to homoioteleuton: eiV ton aiwna - eiV ton aiwna. A scribe added the missing verse in part at the bottom of the last missing page and in part on top of the first existing page."

(W.Willker, Textual Commentary, Vol 4b The Pericope de Adultera, 3rd ed. 2005)

1. [ - credit or reference to Burgon is carefully avoided...]

Willker has made a counter-claim to Burgon, but does not provide evidence in the form of calculations or reconstructed pages. Yet it would seem that to settle the issue, accurate reproductions of the pages should be produced.

The important thing with relatively late 4th or 5th century manuscripts is not whether they contained or omitted the verses. This is secondary. What matters is if they show evidence of any knowledge of their existance, whether they include it or not.

The missing pages in Alexandrinus are important, not because they cloud the issue of whether or not the verses were included, but because important evidence regarding knowledge of the verses, such as a space, a dot, or a critical mark or note, has probably been lost forever.

Had Burgon been given more time to examine both Codex B and  , he would have certainly discovered the critical marks on both MSS, and would have rejected them entirely as any kind of evidence for an 'insertion' after 350 A.D.

, he would have certainly discovered the critical marks on both MSS, and would have rejected them entirely as any kind of evidence for an 'insertion' after 350 A.D.

'Codex X' (10th cent. ms. 033, Munich) is just a 10th century commentary on what was read publicly during services. This obviously disqualifies it as 'MSS evidence' against the passage. Yet this fact is still commonly ignored by textual critics today in presenting the evidence. (see for instance W. Willker, A Textual Commentary on the Greek Gospels, Vol. 4b, The Pericope de Adultera, 3rd ed. 2005, publ. online, where codex X is listed without comment along with ancient uncials omitting the verses, as if it were ordinary manuscript evidence.)

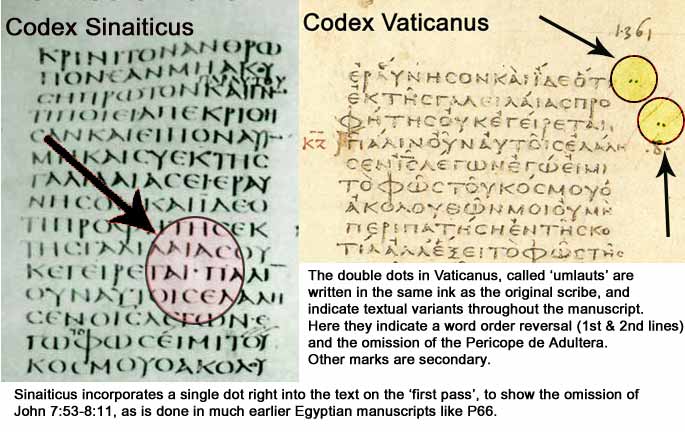

Even Codex B (Vaticanus, 340 A.D.) shows guilty knowledge of the verses, marking the omission with an umlaut, a critical mark in the margin used by the scribe to indicate textual variants throughout the manuscript.

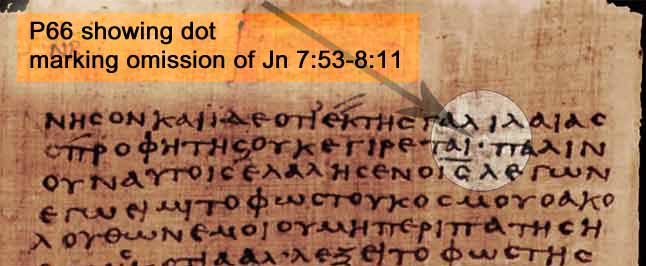

Even when we restrict ourselves to evidence older than 350 A.D., taking codex B, and the three ancientt manuscripts discovered since Davidson's time (codex  - 340 A.D., P66 - 150 A.D., P75 - 200 A.D.), we find that all four, including the oldest (P66), show knowledge of the omission.

- 340 A.D., P66 - 150 A.D., P75 - 200 A.D.), we find that all four, including the oldest (P66), show knowledge of the omission.

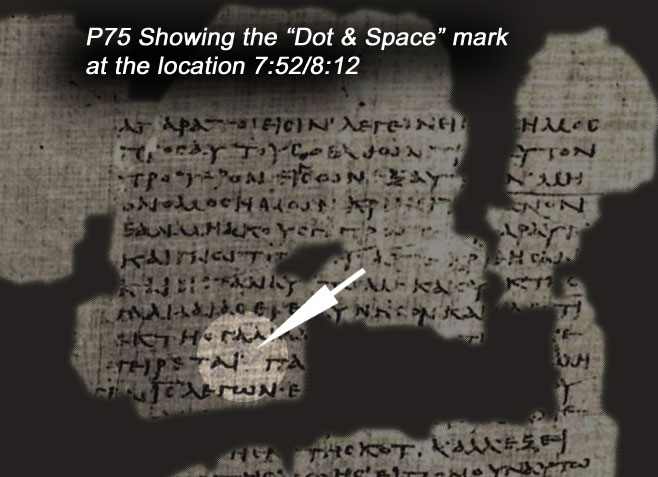

Papyrus 75 (P75) also seems to show awareness of the verses: this manuscript is believed to be about 50 years newer than P66.

The manuscript evidence actually falls into a variety of categories, none of which represent clear-cut evidence for or against authenticity. Nor should we regard the evidence as 'conflicting': Rather, the evidence is ambiguous in regard to authenticity, since this question is an indirect one. We can sum up the early manuscript evidence in a chart as follows:

Early Manuscripts relevant to John 7:53-8:11 | ||

| Codex | Date | Details |

| . | ||

| - blue = mss contains passage. | ||

| - green = mss contains passage but with complications. | ||

| - yellow = mss seems to omit but key evidence is missing. | ||

| - orange = mss omits passage but is aware of it. | ||

| - red = mss omits passage. | ||

| . | ||

| . | ||

| Codex | Date | Details |

| ................ Early Period: 2nd - 3rd centuries | ||

| P66 | 150 A.D. | marks the omission with space and dot. |

| P75 | 200 A.D. | marks the omission with space and dot. |

| P45 | 225 A.D. | portions missing from Jn 5:24 to 10:6 |

| For this early period, the only surviving MSS come from a few sites in central Egypt, where the extreme dryness has preserved them. So they don't offer a wide sample that could represent the state of the text everywhere in the Roman world for this era. | ||

| . | ||

| ................ Time of Constantine: 4th century | ||

| 340 A.D. | marks omission with space and dot. |

| B | 340 A.D. | marks omission with umlaut in margin. |

| From the Council of Nicaea (325 A.D.) to Chalcedon (451) is called the Golden Age. The new peace enabled Christian literature to blossom. The number of NT MSS written in the 4th century was probably between 1500 -2000 at least. Ironically, only 2 copies of John survive, and these more likely reflect the editorial opinion of their sponsors than the true state of the text. | ||

| . | ||

| ................ Byzantine Empire Period: 5th century | ||

| A | 5th cent. | portions missing from 6:50 to 8:52 probably omits |

| C | 5th cent. | portions missing from 7:3 to 8:54 probably omits |

| D | 5th cent. | has passage in Greek and Latin side: no marks |

| T | 5th cent. | Greek/Sahidic Text: omits passage in both. |

| W | 5th cent. | early 'Alexandrian' Text in John: omits passage. |

| Although this handful of MSS reflects the diversity of witnesses for this period, they cannot be taken as representative of the relative number of MSS omitting or containing the verses. The sample size is hardly adequate. | ||

| . | ||

| ................ 6th - 7th centuries | ||

| N | 6th cent. | omits passage. |

| 070 | 6th cent. | portions missing |

| Few MSS of John have survived from 6th century, and apparently none from the 7th century. Its possible however, that some MSS of the 8th and 9th have been dated too late. These two MSS shouldn't be taken as representative of the mass of MSS which must have existed in this period. | ||

| . | ||

| ................ 8th - 9th centuries | ||

| E | 8th cent. | has passage |

| 0233 | 8th cent. | palimpsest: has passage but now unreadable. |

| 047 | 8th cent. | has vs 8:3-11 but omits 7:53-8:2 |

| 8th/9th. | omits passage. |

| F | 9th cent. | missing 7:28-8:10a but had passage |

| G | 9th cent. | has passage |

| H | 9th cent. | has passage |

| K | 9th cent. | has passage |

| L | 9th cent. | marks the omission with a space |

| M | 9th cent. | has passage |

| U | 9th cent. | has passage |

| V | 9th cent. | has passage |

| Y | 9th cent. | omits passage. |

| 9th cent. | missing pages from 8:6 - 8:44 but had passage. |

| 9th cent. | has passage |

| 9th cent. | has passage |

| 9th cent. | marks the omission with a space |

| 9th cent. | omits passage. |

| 0211 | 9th cent. | omits passage. |

| 565 | 9th cent. | has passage |

| 892 | 9th cent. | miniscule mss has passage |

| 1424 | 9th cent. | puts passage in margin with obeli. |

| Over 70% of relevant MSS from 8th / 9th centuries have passage. | ||

| . | ||

| ------------ 10th - 15th centuries ------------- | ||

| S | 10th cent. | has passage |

| 10th cent. | has passage |

| 0141 | 10th cent. | omits passage. |

| X | 10th cent. | - a commentary on public lectionary readings |

| 33 | 10th -11th.* | cursive mss omits passage. |

| 28 | 11th cent. | has passage |

| 700 | 11th cent. | has passage |

| 153 | 12th cent. | omits passage. |

| 1071 | 12th cent. | has passage |

| 1241 | 12th cent. | omits passage |

| 579 | 13th cent. | has passage |

| This is only a sample for this period (10th to 15th cent.). Add also another 1300 contemporary MSS having the passage. That is, over 90% of the MSS from this period contain the Pericope de Adultera. | ||

| * 33 - Although the OT portions may be 9th century, the NT portions are by a later hand dated to the 10th or 11th. (See Gregory, Scrivener) | ||

| . | ||

| . | ||

| . | ||

7. Here we are given an important piece of information, never to be repeated by any subsequent author. That is, of a sample of 46 MSS (available in 1848) which have 'marks', at least 15 of them are actually ASTERISKS, not OBELI. That is, about one third, or 33% of the marked MSS are not marked with Obeli (signs allegedly meaning an 'interpolation'). Davidson is the only critic to make the distinction and actually give us counts.

It would have been more helpful to susequent researchers, although not to his case for omission, had Davidson given the numbers and dates of these MSS, or at least listed which ones had asterisks. The dates are significant, since most of these will be later than the 10 century, and not reliable as 'text-critical' notes regarding the much earlier history of the text.

Extrapolating this to current MSS counts, we can guesstimate that out of about 61 cursive (miniscule) MSS known later to Scrivener (unfortunately without distinction), at least 20 probably had asterisks, not 'obeli' of any form. This is important, since any counting of 'notes of suspicion' must distinguish between the different symbols and their usages.

Maurice Robinson, who has spent considerable time personally collating the Pericope de Adultera, has mentioned (in discussions on TC-List) that many of the marks he examined were apparently simple Lectionary marks, not critical notes at all.

8. Again, the dates for these MSS are significant for evaluating them as records of activities during textual transmission. In fact, later Scrivener increased this count to 13 MSS, namely, 1 (XII),19 (XII), 20 (XI), 129 (XI), 135 (XI), 207 (XI), 215 (XI), 301 (XI), 347 (XII), 478 (X), 604 (XIV), 629 (XIV), and tells us the Evangelistrum is Evst. 86 (XI). Dates are provided from Robinson's Master List. The obvious fact is that these MSS are closely related and all are quite late, the earliest being 478 (10th century).

Also of significance is that this activity of placing the passage at the end of John is not limited to but rather independant of Family 1 (i.e., MSS 1, 118, 131, 209.) Even if Family 1 were found to be an older text than the MSS themselves suggest, this would not apply to the placement of the passage at the end of John.

But perhaps even more important is what the placement of the passage at the end of John means. For the scribes and/or their overseers seem regularly to have meant to correct the omission of the passage in future copies, by adding it to the end with a marginal note or mark at the place where it should be inserted.

In fact, this very point is indicated by the notes in 135 and 301, that tell us they found it "in the ancient copies" (en arcaioiV antigrafoiV). The confusion of both scribes, correctors, and later examiners of these late manuscripts should not obscure the fundamental observation that even in the midst of apparent battles over its inclusion, a significant number of scribes were continuously trying to re-insert the passage.

9. Similarly, when we look at Family 13 (13 (XIII), 69 (XV), 124 (XI), 174 (XI), 230 (XI), 346 (XII), 543 (XII), 788 (XI), 826 (XII), 828 (XII), 983 (XII), 1689 (XIII), ) We are struck by the lateness of the textual evidence for the placement of the passage in Luke. While there is no doubt that Family 13 contains ancient readings, (variants), its existance as a 'text' or 'text-type' cannot be firmly established as earlier than the 9th century.

It seems likely too, that putting the passage after Luke 21:38 was just an attempt to save it from those who had ordered the scribes to remove it. It can hardly have been an attempt to 'reconstruct' a hypothetical longer version of Luke with the passage, by someone in the 11th century.

The mistaken re-insertion by MSS 225 (XII), 1128 (XII) after John 7:36, can only be a bumbling attempt at restoration by scribes late in the day. It has no significance other than to document the amount of ignorance possible in the late 12th century.

10. We have already documented the lateness, ambiguity and unreliability of Euthymius above, and only note again here that he is speaking from the 12th century from his own naive perspective. Euthymius' testimony can have no critical value in sorting out the early history of the passage.

11. Most of the early translations made from Greek into other languages between the 2nd and 5th centuries were independant, amateur productions. They were carried out by converts eager to bring Christianity into their own nations and cultures. This was done by forming a local church, usually poor, and centered around a family home. These 'start-up' churches would borrow older, worn out, and sometimes lower quality copies of scripture.

Most early Gospels were already converted for church use or made for public reading. Naturally, some translations would be made from these Evangelistaria or Lectionaries (lessons collected out of the Gospels), not 'continuous copies' of the original Gospels. Burgon pointed out the early Lectionary system as a source of corruption long ago:

"Liturgical use has proven a fruitful source of textual perturbation. .... [for the previous period] the practice generally prevailed of accommodating an ordinary copy, ... to the requirements of the Church. ...Lessons from the New Testament were probably read in the assemblies of the faithful according to a definite scheme, and on an established system, at least as early as the fourth century...

That it must have been so even in Apostolic antiquity may be inferred from several considerations: [Ed. Miller's Note: "In the absence of materials supplied by the Dean upon what was his own special subject, I have thought best to extract the above sentences from the Twelve Last Verses, p. 207. The next illustration is his own, though in my words."...] . For example, Marcion, in A. D. 140, would hardly have constructed an Evangelistarium and Apostolicon of his own, as we learn from Epiphanius ( i. 311) , if he had not been induced by the Lectionary System prevailing around him to form a counterplan of teaching upon the same model."

(Burgon, Causes of Corruption of the Traditional Text, 1896, Ch. VI, V. para 1f, pg 68f)

Some might object to positing Lectionary practice as the sole, main, or even instigating cause of the omission of the Pericope de Adultera.

But our purpose is far more modest here: We wish to point out only that most of the early translations from Greek into other languages show clear signs of being made from early 'Lectionaries', or copies prepared for public reading. They have many omissions and alterations only explainable by deliberate plan, not through accidental corruption.

Most modern critics acknowledge this, by recognizing that both the Lectionary texts and the early translations are plainly secondary, and they rarely use them as a source of proposed changes to the critical text without serious mainline support from the early uncial MSS.

Since critics don't appeal to the Old Latin or Syriac etc. themselves as corrective sources of any independant weight, it is hardly convincing to appeal to them here in support for a theory regarding the 'later addition' of John of 7:53-8:11.

12. Since Davidson discusses some of the more important early fathers further on, we will limit our criticism to the fact that no dates are provided for this list of twelve fathers. Dates would indicate clearly just how few of them are relevant to the question of the authenticity, or even for a plausible date for 'insertion' of the passage.

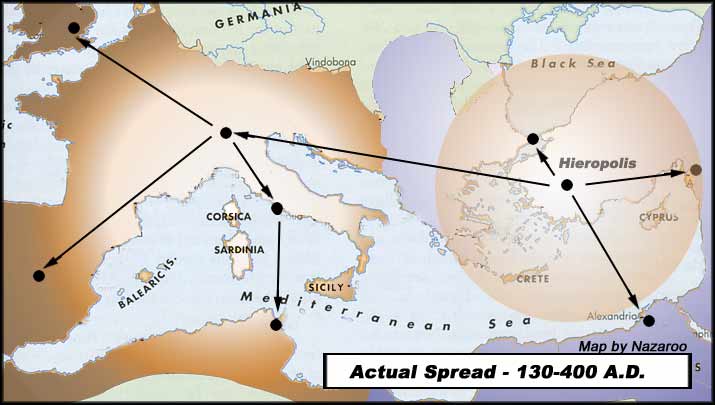

Concerning 'Apollinaris' there are several possible candidates:

(1) Apollinaris the bishop of Ravenna, apparently consecrated by Peter himself, an early martyr leaving little writing behind,

(2) Apollinaris Claudius, bishop of Hierapolis (circa 170 A.D.) who wrote an early Christian apologetic work,

(3) Apollinaris "the Elder" (c. 350 A.D.), who converted the NT into some kind of 'Platonic dialogues', father of...

(4) Apollinaris "the Younger", bishop of Laodicea (350-390 A.D.) condemned for Docetism, and inadvertant 'father' of the Monophysite heretical movement,

(5) Sidonius Apollinaris, Roman Aristocrat and 'saint', (431-480 A.D.) who left behind 9 books of letters.

Only the 4th "Apollinaris the Younger" seems to have written enough works for his 'silence' to be meaningful, apparently exchanging a few letters with Basil of Caesarea as well. Or would be meaningful, if only we had the bulk of his works:

Although Apollinaris the Younger was a prolific writer, scarcely anything has survived under his own name. But a number of his writings are supposed to be concealed under the names of orthodox Fathers, e.g. κατα μερος πιστις , long ascribed to Gregory Thaumaturgus.

Just how precarious the evidence is regarding 'Apollonius' etc. was revealed by Hort:

"One scholium [the marginal note of miniscule 1 (12th cent.)] states that the Section was 'not mentioned by the divine Fathers who interpreted [the Gospel], that is to say Chrysostom and Cyril, nor yet by Theodore of Mopsuestia and the rest...':

... according to another [scholium in the late miniscules 215 (11th cent.), 262 (10th cent.)], it was not in 'the copies of (used by) Apollinarius'. These and other scholia in MSS of the 9th (or 10th) and later centuries attest the presence or absence of the Section in different copies: their varying accounts of the relative number and quality of the copies cannot of course be trusted."

(Hort, Introduction, Appendix: Notes on Select Readings, pg 83)

Hort informs us that the 'silence' of four of these fathers has been presumed from a couple of anonymous marginal notes in 3 MSS from the 10th -12th centuries! He might as well have added that it isn't only the estimates of MSS counts (including or excluding the passage) that 'cannot of course be trusted' in these notes.

13. Davidson describes the text of D as 'a peculiar form unlike that of the received text.' But this is a non-sequiter since he is rejecting the 'received text' in favour of the 'Alexandrian' omission. Hort sensed this inconsistency acutely and so actually adopted the text of D as the primitive text, for his appendix to John in his own critical Greek text. The point is, if you're going to reject the Received Text as a late 'edited' text, you might as well refer to that text as 'peculiar', and credit D with being the 'normal' version of the passage.

14. The 'apocryphal additions' to Matthew and Luke are not relevant or useful in evaluating the text of John in Codex D. For one thing, they are not the same type of variant at all. The Pericope de Adultera is a unique textual problem. Secondly, It is acknowledged that codex D is of a different text-type. www.skypoint.com summarizes Codex Bezae and its difficulties nicely:

Description and Text-type

The text of D can only be described as mysterious. We don't have answers about it; we have questions. There is nothing like it in the rest of the New Testament tradition. It is, by far the earliest Greek manuscript to contain John 7:53-8:11 (though it has a form of the text quite different from that found in most Byzantine witnesses). It is the only Greek manuscript to contain (or rather, to omit) the so-called Western Non-Interpolations. In Luke 3, rather than the Lucan genealogy of Jesus, it has an inverted form of Matthew's genealogy (this is unique among Greek manuscripts). In Luke 6:5 it has a unique reading about a man working on the Sabbath. D and F are the only Greek manuscripts to insert a loose paraphrase of Luke 14:8-10 after Matt. 20:28. And the list could easily be multiplied; while these are among the most noteworthy of the manuscript's readings, it has a rich supply of other singular variants.

In the Acts, if anything, the manuscript is even more extreme than in the Gospels. F. G. Kenyon, in The Western Text of the Gospels and Acts, describes a comparison of the text of Westcott & Hort with that of A. C. Clark. The former is essentially the text of B, the latter approximates the text of D so far as it is extant. Kenyon lists the WH text of Acts at 18,401 words, that of Clark at 19,983 words; this makes Clark's text 8.6 percent longer -- and implies that, if D were complete, the Bezan text of Acts might well be 10% longer than the Alexandrian, and 7% to 8% longer than the Byzantine text.

This leaves us with two initial questions: What is this text, and how much authority does it have?

Nineteenth century scholars inclined to give the text great weight. Yes, D was unique, but in that era, with the number of known manuscripts relatively small, that objection must have seemed less important. D was made the core witness -- indeed, the key and only Greek witness -- of what was called the "Western" text.

More recently, Von Soden listed D as the first and chief witness of his Ia text; the other witnesses he includes in the type are generally those identified by Streeter as "Cæsarean" (Q 28 565 700 etc.) The Alands list it as Category IV -- a fascinating classification, as D is the only substantial witness of the type. Wisse listed it as a divergent manuscript of Group B -- but this says more about the Claremont Profile Method than about D; the CPM is designed to split Byzantine strands, and given a sufficiently non-Byzantine manuscript, it is helpless.

The problem is, Bezae remains unique among Greek witnesses. Yes, there is a clear "Western" family in Paul (D F G 629 and the Latin versions.) But this cannot be identified with certainty with the Bezan text; there is no "missing link" to prove the identity. There are Greek witnesses which have some kinship with Bezae -- in the early chapters of John; the fragmentary papyri P29 and P38 and P48 in Acts. But none of these witnesses are complete, and none are as extreme as Bezae.

D's closest kinship is with the Latin versions, but none of them are as extreme as it is. D is, for instance, the only manuscript to substitute Matthew's genealogy of Jesus for Luke's. On the face of it, this is not a "Western" reading; it is simply a Bezan reading.

Then there is the problem of D and d. The one witness to consistently agree with Dgreek is its Latin side, d. Like D, it uses Matthew's genealogy in Luke. It has all the "Western Non-Interpolations." And, perhaps most notably, it has a number of readings which appear to be assimilations to the Greek.

Yet so, too, does D seem to have assimilations to the Latin.

We are almost forced to the conclusion that D and d have, to some extent, been conformed to each other. The great question is, to what extent, and what did the respective Greek and Latin texts look like before this work was done?

On this point there can be no clear conclusion. Hort thought that D arose more or less naturally; while he considered its text bad, he was willing to allow it special value at some points where its text is shorter than the Alexandrian. (This is the whole point of the "Western Non-Interpolations.") More recently, however, Aland has argued that D is the result of deliberate editorial work. This is unquestionably true in at least one place: The genealogy of Jesus. Is it true elsewhere? This is the great question, and one for which there is still no answer.

As noted, Bezae's closest relatives are Latin witnesses. And these exist in abundance. If we assume that these correspond to an actual Greek text-type, then Bezae is clearly a witness to this type. And we do have evidence of a Greek type corresponding to the Latins, in Paul. The witnesses D F G indicate the existence of a "Western" type. So Bezae does seem to be a witness of an actual type, both in the Gospels (where its text is relatively conservative) and in the Acts (where it is far more extravagant). (This is in opposition to the Alands, who have tended to deny the existence of the "Western" text.)

So the final question is, is Bezae a proper witness to this text which underlies the Latin versions? Here it seems to me the correct answer is probably no. To this extent, the Alands are right. Bezae has too many singular readings, too many variants which are not found in a plurality of the Latin witnesses. It probably has been edited (at least in Luke and Acts; this is where the most extreme readings occur). If this is true (and it must be admitted that the question is still open), then it has important logical consequences: It means that the Greek text of Bezae (with all its assimilations to the Latin) is not reliable as a source of readings. If D has a reading not supported by another Greek witness, the possibility cannot be excluded that it is an assimilation to the Latin, or the result of editorial work.

(Codex Bezae, www.skypoint.com)

15. In fact the paragraph's absence from B and probably A probably doesn't far outweigh its appearance in D at all. What we know now, is that the scribes of B and probably A both had knowledge of the existance of the passage. That gives their omission of the passage an entirely different meaning and significance than the one previously assigned to these witnesses.

16. We have already discussed the true significance of many 'critical marks' in the manuscripts. (see footnote 3 above). Here we only wish to direct the reader who is interested in more detail to our extensive article on 'critical marks' and marginal corrections here:

The Meaning of Critical Marks <-- click here

17. The problem of claiming the Old Syriac to be missing the verses involves two factors: (1) that much of the form and peculiarities of the Old Syriac text seems to owe itself to early Lectionaries used as a base for translation. (2) The Jerusalem Syriac appears to be based upon traditions arising right out of the heart of the earliest Christianity, namely the early Church in Jerusalem itself.

"In the Menology of Syr.hr, 8:1, and 8:3-12 is the Lection for St. Pelagia's Day, as in many Greek Lectionaries."

(Hort, Selected Notes,, p 83)

So as Hort has acknowledged, the ancient Jerusalem Syriac Lectionary tradition includes the Pericope de Adultera as the Reading for St. Pelagia's Day. Although the MSS support here is late, there is strong evidence that these Palestinian forms of Syriac tradition are primary.

18. Interestingly, Hort contradicts Davidson on this point, and argues that Origen's silence is significant. He offers a more careful examination:

"Origen's commentary is defective here, not recommencing until 8:19; but in a recapitulation of 7:40-8:22 the contents of 7:52 are immediately followed by those of 8:12."

(Hort, Introduction, Appendix: Selected Notes, p.83)

However, we should direct the reader to take an extraordinary 3rd step, and examine Origen even more carefully than Hort. There the reader will find between the lines of Origen's exposition on Israel and the Church, repeated references to the Pericope de Adultera, in a not-so-veiled fashion.

Of particular interest will be Book 1 and 10 of his commentary on John, from para. 20 forward, where Origen builds upon his allegories of the Temple, Jerusalem, Israel and the Church.

But even more important evidence than the suggestive language there will be found in Book 14 of Origen's commentary on Matthew, particularly beginning with his paragraph 13 on forgiveness, and on to the end.

19. The silence of Cyprian and its significance has not been adequately demonstrated by either Davidson or Hort 50 years later. They have chosen to expound what they have perceived as the 'easier cases' of Tertullian and Chrysostom.

As to Tertullian, we can only remark that this is appears to be comedy of errors based upon critics being unable to see the forest for the trees. While it is true that Tertullian makes no use of the Pericope de Adultera, he is obviously on the other side of the argument for granting forgiveness to adulteresses.

1. It is in his interest to ignore the verses, and if they were brought up by the opposition, he could doubtless have appealed to the fact that the woman is actually not forgiven at all according to the scripture, but rather her trial was adjourned and postponed, and the passage hardly approves of adultery.

2. If this weren't enough to throw up a red flag, Tertullian himself is not the appropriate choice as an advocate for the omission as an original reading. He is a legalistic fanatic with an incredibly low and ignorant opinion of women. He is so strict and authoritarian that he is described derogatorily as the 'first Protestant' (i.e. fundamentalist extremist).

"Tertullian denounced Christian doctrines he considered heretical, but later in life adopted views that came to be regarded as heretical themselves. ...In middle life (about 207) he broke with the Catholic Church and became the local leader and exponent of Montanism, that is, he became a heretic. But even the Montanists were not rigorous enough for Tertullian who broke with them to found his own sect. ...he declared a Christian should abstain from the theater... that virgins should ... keep themselves strictly veiled. ...and he pronounced second marriage a species of adultery. Tertullian is occasionally considered as an example of the misogyny of the early Church Fathers... "

(http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tertullian, Entry -Tertullian)

3. Tertullian himself gives us a clue of his familiarity with the Pericope de Adultera, in the peculiar language of his misogynistic exaggerations. Its as if he can't help admitting guilty knowledge of the passage in the process of fighting its potential misinterpretation:

"Do you not know that you are Eve? The judgment of God upon this sex lives on in this age; therefore, necessarily the guilt should live on also. You are the gateway of the devil; you are the one who unseals the curse of that tree, and you are the first one to turn your back on the divine law; you are the one who persuaded him whom the devil was not capable of corrupting; you easily destroyed the image of God, Adam. Because of what you deserve, that is, death, even the Son of God had to die."

(De Cultu Feminarum, section I.I, part 2 - trans. C.W. Marx)

The last line in boldface here seems directly inspired by a demonic misunderstanding of the passage. Tertullian, with his temperament, had he read the Pericope, would have perceived in it the provocation of our Lord's crucifixion. And he would have been compelled by his systemic attitude to blame the woman for the entire fracas. In his mind, had she not committed adultery in the first place, she would never have been brought before Jesus, who then had to die because of the political conflict that ensued.

Tertullian's Christian soterology is hopelessly primitive. He is looking for blame and guilt for the crucifixion of Jesus, and finds the woman, and not only this, he extends this blame to all women henceforth. Its incredible that critics have not picked up on this twisted but all too typical misogynist interpretation of John 8:1-11. Contained in his vitriolic rant is strong internal evidence that Tertullian knew the passage, but was incapable of really understanding it or accepting it, or rather took it as he was predisposed to interpret it.

4. But the clincher is this: What is staring us in the face in Tertullian's complaint about the bishop of Rome (or Carthage) issuing an edict for the forgiveness of adultery, is that a bishop must actually have done so. And on what scriptural basis could that edict have been built more plausibly than the Pericope de Adultera? That is, whatever Tertullian had in his 'Alexandrian' text, the bishop clearly had John 7:53-8:11 in his own.

Far from Tertullian's 'silence' being significant, his testimony appears to be the earliest corroborating evidence for John 8:1-11.

20. Nicon and Ambrose are virtually sweeped under the rug here. Davidson must acknowledge their existance as important witnesses to the passage, but Nicon doesn't even rate a quotation. Hort goes a step further, caricaturing Nicon as country bigot:

"A Nicon who wrote a Greek tract On the impious religion of the vile Armenians (printed by Cotelier Patr. Apost. on Const. Ap. l.c.), and has been with little probability identified with the Armenian Nicon of Cent. X, accuses the Armenians of rejecting Luke xxii 43 f. and this Section, as being "injurious for most persons to listen to": like much else in the tract, this can only be an attempt to find matter of reproach against a detested church in the difference of its national traditions from Constantinopolitan usage.

(Hort, Introduction, Appendix, Selected Notes, pg 82)

The sketch of Nicon as country bumpkin with a provincial bias is wholly fictional, as well as the attempt to limit Nicon's province or experience to 'Constantinople'. Everything Hort wishes to dismiss as late seems to become 'Constantinopolitan'. In fact, Nicon, if he did live in Constantinople, would have been at the center of the Cosmopolitan (a better adjective here) Byzantine Empire, its main capitol.

Nicon is an important witness, because he breaks the 'rule' that Davidson and Hort want to proclaim: namely that the Greek fathers (as opposed to the Latin ones) did not speak about the verses, and hence did not know of their existance. Obviously a Greek father writing from downtown Constantinople would press inconveniently upon the theory.

21. Dismissing Ambrose with a single line of obscure Latin may have been invented by Davidson as a way of downplaying the evidence of the earliest father (c. 360 A.D.) to witness plainly and clearly about the passage. But it was Hort who took the trick and developed it into an artform, not only mimicking Davidson here, but applying the gag to Faustus and others as well:

"Amb. [Ambrose] 2 Ep. i 25 speaks of semper quidem decantata quaestio et celebris absolutio mulieris."

"...one of [Augustine's] quotations from his contemporary the Manichean Faustus includes a reference to Christ's 'absolution' of in injustitia et in adulterio deprehensam mulierem (xxxiii 1). "

(Hort, Introduction, Appendix, Selected Notes, pg 82)

This kind of childish elitism was rampant in the 19th century, when the ability to read Latin was still the 'litmus test' for the educated and upper-class. Basically, if you couldn't read and parse ancient Latin on your own, you were out of the loop.

Such obscurantism can have no place in a modern scientific work, even from a specialist. Plain communication between disciplines and outside of one's field or specialty is absolutely essential to scientific progress and good writing.

22. Davidson's own conjectures about Augustine's testimony are interesting, but not germaine to the question. It is not the value of Augustine's opinion about causes that matters, but his firm witness to the existance of MSS which contained the passage.

For the purpose of establishing the popularity and extent of the passage's presence in the MSS tradition, it is only Augustine's acknowledgement that many MSS must have contained it that counts. He is a credible enough witness as to what he handled and saw with his own eyes. His opinions of the motive of others, whose handiwork he clearly examined, are superfluous.

23. Various other possibilities as to original causes and subsequent influences on the omission or inclusion of the passage must certainly be considered. But if by 'cannot be shewn' Davidson means cannot be 'proved', well this is simply special pleading.

We can hardly just dismiss Augustine's opinions. He was instrumental in reconciling the later followers of Tertullian back to the church, who had fallen into Docetist and Monophysite heresies. He would certainly have known some of the textual history of Tertullian's text and those used by subsequent heretics.

Of course we don't know for sure why the passage was first removed, or even who later found such an omission convenient to their own agendas, such as perhaps Tertullian. But this hardly deters us from trying to reconstruct the most plausible forces and events involved, or holding the door open to various scenarios if the evidence is ambiguous.

24. This assertion by Davidson is simply naive. The re-insertion or omission of verses 3-11 in some late copies, in the final period (1000 - 1500 A.D.) has nothing at all to do with what Augustine said at the close of the 4th century. This just reflects the last throes of a confused battle that continued for nearly a thousand years.

What this really represents is that some scribes were using the Lectionary text (which only had 8:3-11 as a unit) as a guide to remove the verses, inadvertantly leaving in verses 7:53-8:2. This clumsy attempt at altering John is transparent, and was noted by von Soden as early as 1910.

25. The battle over the meaning of Chrysostom's 'evidence' is essentially irrelevant to the question of authenticity. Yes Chrysostom seems to have left out a discussion of John 8:1-11 from his commentary. But this only reflects the late (5th century) practice of the Lectionary traditions.

Although Chrysostom's opinion is historically interesting, it comes too late to bear on the question of the origin and authenticity of the Pericope de Adultera.

As Davidson concedes, the passage must have been read publicly in church, and is found in the Lectionary traditions of both the Greeks and Latins. This larger longstanding tradition overwhelms the opinion of any particular early father, whatever his thoughts might have been.

26. Davidson says,

"it cannot be shewn that the greek church had it in their MSS before the fifth century; or that the Latin church had it before the fourth."

As Hort does after him, Davidson tries to limit the passage to the Latin fathers and the Latin MSS during the 4th century. But this reflects a naive belief that the fragmentary MSS evidence is somehow of greater authority than the testimony of the early fathers, the men who actually lived and worked with the manuscripts of the period.

But this won't wash. All three of the big Latin fathers (Ambrose in Milan, Jerome in Rome, Augustine in Hippo) confirm or imply its presence in the Greek MSS of the 4th century as well as the Latin. The state of the Greek MSS cannot be ascertained on the basis of the two sole surviving MSS (Aleph, B) out of at least 2000 that must have existed. Hort admits as much:

"The facts of textual history already recounted, as testified by versions and patristic quotations, shew that it is no longer possible to speak of 'the text of the 4th century', since most of the important variations were in existance before the middle of the 4th century, and many can be traced back to the 2nd century.

Nor again, in dealing with so various and complex a body of documentary attestation, is there any real advantage in attempting, with Lachmann, to allow the distributions of a very small number of the most ancient existing documents to construct for themselves a provisional text."

(Hort, Introduction,Part IV. para 375, pg 288)

While methodologically textual criticism begins with extant documents, the weight of historical evidence cannot be ignored in deference to a few MSS with their own peculiarities.

Nor does the direction in which the passage allegedly travelled to enter into the Greek (Eastern) MSS, (i.e., from West to East) appear convincing. Davidson ignores the testimony of Eusebius, but Eusebius very plainly locates the earliest testimony for the passage in Turkey just after 100 A.D.:

"Eus. [Eusebius] H. E. iii 39 16 closes his account of the work of Papias (Cent. II) with the words,

"And he has likewise set forth another narrative ( ιστοριαν) concerning a woman who was maliciously accused before the Lord touching many sins ( επι πολλαις αμαρτιαις διαβληθεισης επι του κυριου), which is contained in the Gospel according to the Hebrews".