Return to Index

Introduction

This interview was originally broadcast on Dec 14, 2005, for the purpose of promoting Bart Ehrman's book, Misquoting Jesus, which alleges that the Bible familiar to Christians suffers from serious additions and omissions which are not original to the text.

The interview can still be played over the internet from this location:

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5052156

There is an audio feed (a 'Listen' Button) on the page advertising Ehrman's book.

The Broadcast:

The nature and seriousness of this broadcast can be measured by a statement from NPR (National Public Radio, U.S.A.) about itself:

"A privately supported, not-for-profit membership organization, NPR serves a growing audience of 26 million Americans each week in partnership with more than 800 independently operated, noncommercial public radio stations. " (from the About NPR page online). Since 1987, WHYY-FM has produced a daily, one-hour national edition of 'Fresh Air' ... it now airs on 160 stations."

NPR (National Public Radio, USA):

Although presented as a 'non-profit' (i.e., 'charitable' type) organisation, it is a large fully commercial venture, with many employed professionals. Although not overtly funded by big business, and hence 'independant' of same, the operation has equivalent connections to government and academic institutions, and also receives private (corporate) funding:

"NPR supports its operations through a combination of membership dues and programming fees from over 800 independent radio stations, sponsorship from private foundations and corporations, and revenue from the sales of transcripts, books, CDs, and merchandise."

The Interviewer: Terry Gross

Producer of 'Fresh Air', a national radio program

Similarly, the interviewer is not just a lightweight actress or advertising puppet:

"Gross began her radio career in 1973 at public radio station WBFO in Buffalo, New York. There she hosted and produced several arts, women's and public affairs programs,...2 years later, she joined WHYY-FM as producer and host of Fresh Air,...In 1985, WHYY-FM launched a weekly edition which was distributed nationally by NPR.

The show has received a number of awards, including the prestigious Peabody Award in 1994 for its "probing questions, revelatory interviews and unusual insight."

Terry Gross has a BA in English and an M.Ed. in Comm. from SUNY. Gross has been honored with a 1989 Honorary Doctor of Letters from Drexel U. and a 1993 Distinguished Alumni Award from SUNY also.

Obviously Ms. Gross is well connected academically and has been groomed for a high profile, politically correct career.

(info taken from NPR website)

Bart Ehrman: Controversial Scholar

Author of "Misquoting Jesus"

From his own curriculum vitae, we learn:

"Bart Ehrman is the James A. Gray Distinguished Professor and Chair of the Department of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He came to UNC in 1988, after four years of teaching at Rutgers University.

"Prof. Ehrman completed his M.Div. and Ph.D. degrees at Princeton Seminary, where his 1985 doctoral dissertation was awarded magna cum laude. Since then he has published extensively in the fields of New Testament and Early Christianity, having written or edited nineteen books, numerous articles, and dozens of book reviews."

Return to Index

The Interview: Discussion

All this however, only partially prepares us for the interview to follow. The entire interview, as posted on the NPR site flogging Ehrman's book, is about 35 minutes. However, only the first 8 minutes directly focus upon John 8:1-11. After that follows a discussion of various other example readings and textual problems. Only once more is John 8:1-11 indirectly referred to in passing as an apparent flaw in the King James Version (for having included it).

We cannot forget that the purpose of the interview is purely to promote the ideas of, and interest in the book, which has an openly secular humanist agenda. Ehrman targets and undermines Christian fundamentalism, perhaps even Christianity in any form. This agenda is shared by the two academics who produced the interview.

It should also be understood from what we've noted that this 'interview' is a very professional piece of work. It is pre-written, and carefully performed by these two skilled actors, both known for their didactic, rhetorical, entertaining and acting skills, and their liberal/left academic outlook.

Normally all such interviews are prepared and pre-formatted for their audience or target. Sometimes they are rehearsed, certainly they are discussed, and often pre-recorded. Their normal purpose is simply book promotion, and so the questions are at least approved, if not prewritten by the author and/or his publishers/handlers. The publishers in turn, usually foot the bill for the 'service' (air-time and exposure). This is all just marketing and promotion.

Something 'Special':

Yet this interview is unusual on a few levels:

In spite of the reputation of the interviewer, and the expertise of the author, the interview clearly misleads the listener through a comedy of errors to a ridiculous conclusion. The conclusion is so at odds with the known and agreed upon facts, that it can only be a deliberate deception by at least one if not both parties.

(1) It is implied that the Pericope de Adultera (John 8:1-11) has been somehow accidentally added to the Bible sometime in the Middle Ages by error-prone and unsupervised scribes.

(2) The discussion leaves the unwary listener believing that the bible is just full of stories that have been accidentally and sometimes deliberately added by incompetant, carefree scribes.

But the basis for these two impressions is not any kind of historical fact or accurate scholarship: Instead its a merry-go-round of nonsense, carefully crafted to lead the listener into a kind of maze, and leave him there in total ignorance.

Return to Index

Interview Highlights

Here we provide the essential highlights of the interview excerpt. This can be double-checked by referencing the complete transcript of the excerpt further below. We are in no way altering the key points or basic thrust of the talk. Nor should this short synopsis of the excerpt be considered adequate to describe the full impact of the 8 minute speech. It does give a fair taste of the actual interview, and will assist the reader in noting the problematic content.

Q1: "how the Bible was hand-copied for almost 1500 years":

The period before 'movable type' is introduced, i.e., before 1500 A.D... we are told that the 'Kinko's' of the ancient world was the little scribal shop on the corner. Book copying is a 'painstaking' error-prone process. Scribes are introduced as "careless, possibly tired, inept," and "sometimes scribes actually change the text intentionally". We are told, "once of course they changed the text the change was made permanent" and recopied.

Q2: the story "scholars say was changed" - John 8:1-11:

We are told immediately, "Well, its a terrific story": Ehrman then tells the recognized version of the story in his own words, with a quick aside about the 'dilemma' posed to Jesus by the Pharisees.

Q3: "What's historically questioned in this story?"

"As it turns out, ...this story probably was not original... The earliest manuscripts we have of John don't have this story. ...none of the Greek writing church fathers who comment on the gospel of John include it in their commentaries until the 12th century. ..."

" In the Middle Ages, apparently a scribe...wrote it down in the margin of a MSS (manuscript). And some other scribe came along and saw this story in the margin..., and then transferred it into the MSS itself,...And from then on that MSS got copied, ..."

"...and one of the subsequent copies ...was used then by the KJV translators. ...but it wouldn't have been known at all to Greek reading Christians... in the ancient world. "

Q4: "What might have led a scribe in the 12th century to add this story?"

"Well its a terrific story. ...this [story] illustrates the point being made in John chapter 7 and 8, and I suppose a scribe was reading John 7 and 8 ...and thought 'you know this story I've heard fits right in here, I'll put it in the margin...', uh for it then later to be copied into the text."

Q5: "- the scribes ... - they could just add a story?"

"Well its shocking but uh, you know, its shocking to my students just how often these scribes would change their texts.

...But in the ancient world they didn't expect their books to be like [ours] because they knew ... that mistakes were always being made, so that the very first copy of a book probably had mistakes. And then the person who copied that first copy, copied the mistakes, and added some of his own...

Some scribes felt completely free to change their texts. And would add stories, or take out stories, .... the reason we know it happened is because we have these thousands of surviving manuscripts, and when you look at these, ...the striking thing is just how different they are from one another.

Q6: "So what are you suggesting here,...?""

"I think Christians ...have to make a decision -... Is the original text as it was originally written, is that authoritative? If thats authoritative, thats a problem because we don't have the original texts....

But on the other hand, does somebody want to ascribe authority to a text that was clearly and certainly added later to the bible, such as the story of the woman taken in adultery?

If you ascribe authority to these stories that were added later, ...where do you draw the line? Does it mean anybody can add something to the bible, and then it can count as scripture? This strikes me as a very difficult theological problem...

Return to Index

Full Transcript

We have carefully transcribed the first 8 minutes of this 'interview' with extreme accuracy, in order to show the smallest details, both in content and delivery, of the fantasy these two professionals have concocted. We have even recorded pauses and minor vocative expressions and color-coded them for easy notice.

You can also listen to the Audio Exerpt (mp3) from the original broadcast as posted on NPR, downloaded on Nov. 10, 2006, and quoted here for critique and review purposes:

Interviewer: "This is 'Fresh Air', I'm Terry Gross: There's a bumpersticker that reads, 'God said it, I believe it.'. I guess Bart Ehrman's reaction to that is, "Well what if God didn't say it? What if the book you take as giving you God's words, instead contains human words?".

"Ehrman is the author of the new book, Misquoting Jesus. Its about how the New Testament was altered by the scribes who handwrote each copy, and in the process made intentional, or unintentional changes.

"Ehrman chairs the department of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He's a scholar of the New Testament and the early church. He was 'born again' at the age of 15 and studied at the Moody Bible Institute. Later while attending Princeton Theological Seminary, he started to have doubts about the literal interpretations of the Bible. He now describes himself as an agnostic." 1

Question 1

Interviewer: "Lets start with how the Bible was hand-copied for almost 1500 years:"

Ehrman: "With the Bible we're talking about a period before there was 'movable type', and so, ah, 2 for books to be reproduced they had to be copied by hand, uh, and so all of the books of the New Testament, and all of the books in fact from all of antiquity were reproduced by hand, which is a very slow, painstaking process.

To mass produce a book in the ancient world meant that you would give the book to a uh to a company that, that did these things, and they might have five scribes there, who would copy the book, and so the mass production, or the uh, the uh 'Kinko's' of the ancient world was the little scribal shop on the corner where you might have five guys doing this, to mu- to make a living. 3

Uh so the books, the books got copied out by hand, and uh copying a book by hand of course meant copying out one sentence, one word, one letter at a time. Uh, and uh, and that's, that's not only a painstakingly slow process its also uh lee- the process is open f-for mistakes to be made: 4

Either, uh, accidental mistakes as a scribe is just being, uh uh careless or possibly he's tired or possibly he's inept, uh, and sometimes scribes actually change the text intentionally, when they think the text ought to say something different from what it does say they - they could change the text. - And then once of course they changed the text the change was made permanent, because this was the copy then that somebody else would use, who copied the text later. 5

Question 2

Interviewer: "Lets look at one of the-the classic stories in the New Testament..that, um, yu-yu- you say scholars, say was changed, in- in- in- changed by scribes: and this is the story of the woman caught in the act of adultery, tell it - tell the story as we know it:"

Ehrman: "Well, its a terrific story, 6 its found in uh the gospel of John, chapter 7 and 8, uh the uh Jewish leaders have caught a woman committing adultery and they bring her to Jesus, uh and they set a trap for Jesus. They they ask him, uh they say, uh "According to the law of Moses uh this woman should be stoned to death. What do you say?"

(So Jesus is put in this predicament because if he if he says, uh "No have mercy on her", uh as as you would expect him to say, since hes been preaching a, a doctrine of love and mercy, -if h- if he says that, then he's uh he's breaking the law of Moses: but if he says, No, go ahead and stone her, then obviously he's violating his own teachings about love and mercy. And so what's he to do,)

well he - he stoops down and starts drawing on the ground and he looks up and he says, "Let the one wuh- without sin among you be the first to cast a stone at her", and then he swoo- stoops back down and starts writing again, and slowly one by one all of her accusers leave until he looks up and sees that she's alone and she- he says then to her, uh - are - "is there no one left to condemn you?" And she says, "No lord. no one", and he says "neither do I condemn you, go and sin no more."

Question 3

Interviewer: "What's historically questioned in this story?"

Ehrman: "Well its, the the whole story it its a very interesting story for a lot of reasons, interpreters have puzzled over it over the years, one of the luh leading questions is, If this woman was caught in the act of adultery, where's - where's the man? [chuckle] - because uh according to the law of Moses both of them are to be stoned to death but apparently they've only come away with the woman. So there are interesting interpretive questions.

The the bigger issue is whether uh in fact uh this is a story that belongs in the bible or not. As it turns out, even though this is a favourite story of people who uh who read the bibles and who make uh movies about the bible uh for hollywood, uh uh this story probably was not original to the gospel of John. 7

Uh the earliest manuscripts we have of the gospel of John don't have this story. 8 And none of the Greek uh writing church fathers, (the- the NT of course itself was written in Greek,) none of the Greek writing church fathers who comment on the gospel of John uh include it in their commentaries until the twelfth century. 9 So twelve hundred years after the book itself was, was written. This shows that the early manuscripts simply didn't have the story. 10

ah So then the question is how did w- we get the story? Well in the Middle Ages, uh apparently a scribe knew the story, had heard of the story someplace, through somebody telling him the story and wrote it down in the margin of a manuscript. 11 And some other scribe came along and ss- saw this story in the margin of a manuscript, and then transferred it into the manuscript itself, uh, for the - in the gospel of John. And uh from - from then on that manuscript got copied, 12

uh and one of the subsequent copies of that manuscript, is the, was the copy that was used then by the King James translators when they translated the bible, 13 so that this story has become totally familiar to people who read English, but it wouldn't have been known at all to Greek reading uh, uh Christians reading the gospel of John in the ancient world. 14

Question 4

Interviewer: "Can you explain a little bit more what might have led a scribe in the twelfth century to add this story?"

Ehrman: "Well its a terrific story.

In the gospel of John right at this point, Jesus is condemning his opponents for not judging one another fairly by not having a right judgement, and this is a story that in a way encapulates that idea, that judgement is to be a righteous judgement and that mercy is more important than judgement, and so this illustrates the point being made in John chapter 7 and 8, 15 and I suppose a scribe was reading John 7 and 8 and thinking about it and thought you know this story I've heard fits right in here, I'll put it in the margin, uh for it then later to be copied into the text.

Question 5

Interviewer: "I mean, did the scribes have that much freedom in the work that they could just add a story?" 16

Ehrman: "Well its shocking but uh, you know, its shocking to my students just how often these scribes would change their texts. 17 We, we tend to think that, - in our setting, today when a book is produced, its always the same book, so I can go out and buy a copy of the Da Vinci Code, and it doesn't matter what city in America I buy the copy, its exactly the same copy word for word the same, and so that's what we expect of our books.

But in the ancient world they didn't expect their books to be like that because they knew that these things were always being copied by hand, and that mistakes were always being made, so that the very first copy of a book probably had mistakes. And then the person who copied that first copy, copied the mistakes, and added some of his own mistakes, and then that third copy was itself copied, and its mistakes were replicated then down through the line and so mistakes multiplied through the copying process. 18 Some scribes felt completely free to change their texts. And would add stories, or take out stories, 19 would add lines, take out lines - we know this happened, this isn't just speculation - the reason we know it happened is because we have these thousands of surviving manuscripts, and when you look at these thousands of manuscripts, the striking thing about them is just how different they are from one another. 20

Question 6

Interviewer: "So what are you suggesting here, that we should just ignore that story of adultery, that that story has less currency than other stories in the NT, or that we should just see that as a story that was added later and take it as that, I mean how does that affect your reading of that passage in the bible, what do you make of it?"

Well, its a very good question and I think Christians who see the bible as authoritative have to make a decision - what is it that they think is authoritative? Is the original text as it was originally written, is that authoritative? If thats authoritative, thats a problem because we don't have the original texts, in many instances. 21

But on the other hand, does somebody want to ascribe authority to a text that was clearly and certainly added later to the bible, such as the story of the woman taken in adultery? 22

If you ascribe authority to these stories that were added later to the bible, where do you draw the line? 23 Does it mean anybody can add something to the bible, and then it can count as scripture? This strikes me as a very difficult theological problem that theologians probably need to work on a little bit to tell people what actually is the bible that is being trusted as the authoritative scripture. 24

Return to Index

Footnotes:

1. With the suggestion that the bible just contains 'human words', and the frank announcement that Ehrman is a self-described agnostic, the basic demographic of listeners, namely fellow secular humanists, moderns, and academics, are warmly reassured, while at the same time, lukewarm semi-Christians and the curious are hooked.

The credentials of the guest are also meant to establish an 'expert authority', whose information is to be trusted like a 'father-figure'. The story of Ehrman's early 'born-again' experience is also designed to hit sympathetic chords and some parallel personal experiences from the North American middle-class demographic, the target also for the book sales.

It's important to note that in the first few paragraphs of introduction here, the interviewer speaks clearly and articulately, intending to convey intelligence and gravity. She is already well known, with a loyal fan base of modern working and career women. She is a longtime professional public speaker and interviewer, and this is her normal mode of speech. We note this because of the change in speech pattern which follows shortly!

Return to footnote 1 reference above

2. Here we see the beginning of an unusual phenomenon in Ehrman's speech-pattern. Normally, a few throat-clearings or pauses in the first few paragraphs is a common occurance, but in a few seconds the speaker overcomes (forgets) any initial stage-fright or timidity, and becomes engrossed in the subject.

Here the opposite effect occurs: as Ehrman warms up to his subject, he accelerates his humming and hawing, even exaggerates it painfully. By the third paragraph he is actually stuttering occasionally:

But Ehrman is not suffering from a speech impediment, or any detectable mental impairment. This is in fact "academic-speak": Every college freshman learns to talk in this strange 'hum-haw' stammer-like speech within a few semesters, picking it up from professors and T.A.s, and quite naturally interpreting it as an external badge of 'intelligence'.

Most university students become masters of this speaking technique with little effort, and it becomes a habitual, eventually unavoidable mannerism when giving 'expert opinion' in public debate.

In academic environments, "academic-speak" actually serves a function, allowing students to keep up with the lecturer, and providing cues for key facts and logical connections.

Psychologically, a slight stammer invokes human frailty, an air of humility, and sympathy or endearment from the listener, making them more receptive to instruction. Of course, it is also a blatantly artificial gimmick, similar to suggestion, hypnotism, or other body-language techniques.

Professional actors and salespeople also consciously mimick and rehearse this mannerism as a trade tool.

But what is of interest to us is its forensic, or law enforcement aspect.

Because it becomes a habitual mannerism, and to some extent less controllable, especially when conscious attention is elsewhere, it also becomes a significant 'stress' indicator. Here we see that while stress builds during the first question, as Ehrman tells his dubious tale, it peaks out as soon as the direct question of the Pericope de Adultera is asked.

We can take 5 'hum-haws' per paragraph as Ehrman's 'norm', at least when discussing this subject. He is able to intersperse less plausible statements with incidental facts and reasonable or neutral statements. But few people have enough self-control to consistently beat a 'lie-detector' test, or supress a variety of stress indicators.

It is also remarkable that the interviewer picks up on Ehrman's 'hum-haw' mannerism and mimicks it throughout her second question. It is difficult to tell whether Ms. Gross does this as part of her own professional methodology in an attempt to relax her guest, or lapses into it habitually as a result of her academic experience, or even whether it is an unconscious form of flattery toward her highly academically ranked 'superior'.

It is hardly likely to be her 'normal' mode of interview, although we need more samples to be sure. Her version is not as sophisticated, and is more of a simple stammer, whereas Ehrman's mannerism includes more gestures meant to give the appearance of 'deep thought' or mental struggle.

The signs peppered throughout this speech are quite an interesting study all by themselves.

Return to footnote 2 reference above

3. The actual subject was, "how the Bible was hand-copied for almost 1500 years". Ehrman paints a picture of small 'mom and pop' businesses, something like a shoe-repair. This of course is an absurd and completely misleading picture of how the bible books were copied, even at the time of Jesus.

In fact, even in 200 B.C., the bulk of O.T. Scriptures were made in relatively large scale operations, professionally organized and strictly run. The materials were rare and expensive, and there was a 'zero tolerance' policy regarding sloppiness. Even in Egypt, where papyrus was plentiful and relatively cheap compared to animal skins, the scribal profession was a large and longstanding, well organized trade.

But the most important correction to this vague babble is that from about 200 A.D. until the 15th century, the Bible books made by Christians were copied in organised Scriptoriums by professional scribes, most often Christian monks. These also were relatively large-scale operations, well organized and disciplined.

Typical Medieval Scriptorium:

Finally, even if in smaller towns or churches Christians ran local operations something like Ehrman's picture, this would have been the 'rule' only for the short period up to about 200 A.D., after which Christian activity was widespread, organized around major commercial centers, and well supported.

So why doesn't Ehrman discuss the 1300 years covering 85% of the copying period and actual practice, and 99% of the existing manuscripts? Because that description would work against the conjecture of easy errors and 'insertions' he is trying to paint.

Return to footnote 3 reference above

4. Every process is open to mistakes. However, the 'difficulty' of scribal work should not be exaggerated. It was a prestigious job requiring careful training and obvious literary and calligraphic skills, and scribes had a highly honoured professional-class status.

It was also a highly competative craft, attracting brilliant and talented people, and it sure beat digging ditches. Especially in larger centres such as Alexandria, employers had their pick of the best. Scribes would be unlikely to be careless, 'tired', inept, or dishonest for very long in a tough job market without 'welfare' or unemployment programs.

Return to footnote 4 reference above

5. Ehrman describes a sequential and cumulative process, which is completely unlike the copying procedures known for hundreds of years before Christ. In fact, there were several important quality control steps which would hardly if ever be left out.

Manuscripts were first copied using techniques designed to minimize and eliminate potential errors. Methods were employed involving layout, segmentation, line and letter counting, proof-reading, and cross-checking with other copies, and also submission to overseers who imposed quality controls over materials and labour.

For most of the 1500 year period, production was compartmentalized and the work distributed among copyists, correctors, binders and inspectors. Common errors were well known, and most immediate (new, 1st generation) gaffs were easily caught.

Although some errors could slip through the net for multiple 'generations' (copies), even these would normally be short-lived in the overall transmission streams. Even stubborn errors prone to be repeated independantly would usually have a limited influence in a sea of correct readings to which they were compared through simple public usage.

Comparison and cross-pollination might occasionally perpetuate a 'bad' reading, but more often the act of mixture would slow the process of corruption down to a crawl, in the same way that copious water dilutes a spot of dirt or poison.

Very few individual variants could ever really remain wholly undetected and become 'permanent' in the sense Ehrman implies. Every variant would have its perpetual competing reading, which rarely vanished from of the transmission stream.

Return to footnote 5 reference above

6. Ehrman the story-teller now reassures his unnerved listeners who are stirred up by talk of 'errors' and corruptions. He makes them listen to a 'sympathetic' account of the very passage that he will soon smear as a fraudulent insertion. Ruffled church-goers will be put to sleep by the anti-climactic and utterly familiar version of the story. Meanwhile the suggestion of possible 'errors' in the Holy Scriptures is left to percolate and fester.

Return to footnote 6 reference above

7. By a clever hint of 'guilt by association' with Hollywood, Ehrman implies the story simply makes great fiction, and the shoe is dropped:

"As it turns out, ... this story probably was not original...".

'As it turns out' however, Ehrman not only fails to give us a solid case for an 'insertion', - he actually just spins a mythical tale. Instead of a serious, scholarly and informative talk we get a fraudulent piece of Orwellian newspeak. He treats his audience like a gaggle of dunces.

Return to footnote 7 reference above

8. "The earliest MSS ... don't have this story." ( - Bart Ehrman )

If there were awards for the special art of lying by giving the least amount of truth in the shortest and most misleading manner, this would surely win a grand prize.

The Real Facts about the Manuscripts:

a) Over 1200 MSS, ranging in date from the 5th to the 15th century, have the story.

b) Over a 1000 Lectionaries covering the 7th to the 15th century also have it.

c) Less than 50 MSS, (10th century or later), add critical marks in the margin.

d) Less than 20 MSS, (9th century or later), misplace the story somewhere else.

e) About 25 MSS, (ranging from the 5th to the 15th century), omit the verses.

f) 4 early MSS (2 from the 2nd cent., and 2 from the 4th cent.), omit the verses.

g) 3 out of 4 of these 'earliest MSS' show awareness of the verses with critical marks.

Important Facts about the Manuscripts

Early MSS are extremely rare. The number of Greek MSS written in the 4th century is estimated to have been about 1500-2000. But we only have a dozen or so manuscripts and useful fragments from this period.

But this is hardly a 'Christian specific' problem. When we come to the late Roman, pre-Christianized world, we are confronted with a general lack of information:

"...No reliable accounts of the events of this time period (220 - 400 A.D.?) have been found.

It is generally accepted by scholars that the Historia Augusta is unreliable as history from about A. D. 222 onward. At this point, it assumes the character of a collection of fairy tales and anecdotes of mystical or supernatural happenings.

"There are short biographical sketches of the Roman rulers and family members in many of the Roman coin reference books, but even these scholarly works are in disagreement as to what happened...

"...Since so few reliable accounts of the Third Century exist, this is a field in which a researcher can actually uncover new and unknown information. Perhaps there are original letters or other documents lying in an forgotten corner of the Vatican library or the library of one of the great old universities of Europe. Perhaps someone will find a papyrus preserved in the dry sands of Egypt where most original documents of the period that are still readable have been found. In any case, if possible source materials do come to light, they will need to be translated and compared with other fragmentary evidence of the period."

(exerpt from http://www.crystalinks.com/romewomen2.html)

The Two Earliest Manuscripts:

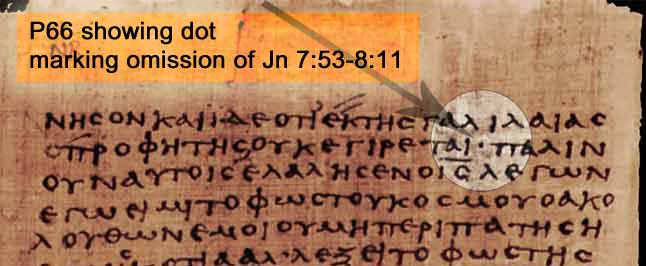

For whole early period of 60 A.D. to 300 A.D., we only have two almost complete copies of John useful for textual questions, P66, and P75. Both of these come from central Egypt, and only survived due to the dry desert climate.

The oldest manuscript, P66 (150-200 A.D.) shows an awareness of the existance of our passage. It marks the omission with a dot. Although P75 apparently has no similar mark, it was made about 25 to 50 years later.

The 'critical marks' in MSS do not indicate 'interpolations' or fraudulent insertions, but rather the existance of alternate readings. They rarely imply the text is in error: What is believed to be the 'best' reading is naturally the one placed in the text by convention. Sometimes the critical marks don't indicate 'variation' at all, but merely mark a passage of importance.

In other cases, the 'critical mark' just notes the beginning and end of a Lectionary section, or 'Lesson'. Often the critical marks are placed there by a much later unknown hand, of dubious authority. Later owners often personalized MSS with marginal notes, just as book owners do today. The majority of such marks occur in extremely late MSS and are of no critical value.

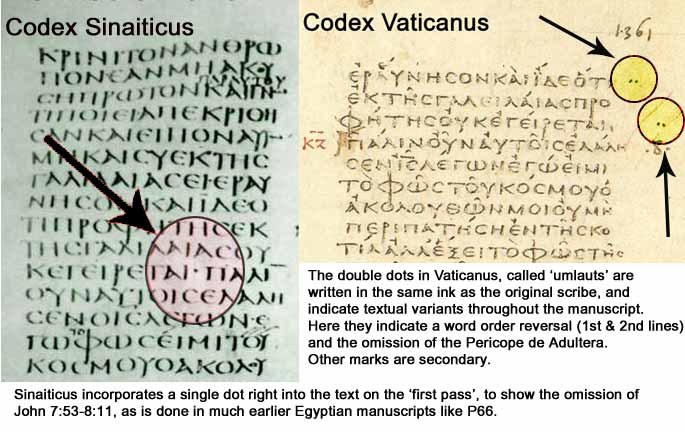

The Two Famous 4th Century Manuscripts: Aleph and B

The two 4th century manuscripts, Codex Sinaiticus ( /01) and Codex Vaticanus (B/02), tell a similar story. Both show knowledge of the passage as an alternate reading:

/01) and Codex Vaticanus (B/02), tell a similar story. Both show knowledge of the passage as an alternate reading:

It is also true however, that early fathers like Ambrose (360 A.D.) and Jerome (380 A.D.) claim to have found it in many MSS considered reputable and old in their own time (both Greek and Latin), and they viewed this well known passage unhesitatingly as authentic.

So while it is technically true that these two 'early' manuscripts,  and B (325-360 A.D.) leave them out, the verses seem to have been already well known at that time.

and B (325-360 A.D.) leave them out, the verses seem to have been already well known at that time.

Constantine and Eusebius: Tweedle-dum and Tweedle-dee

There are good reasons why most textual critics today no longer feel a special attraction toward these two manuscripts. They were most probably written under the supervision of Eusebius, by order of Emperor Constantine.

Eusebius was known to favour the Alexandrian text, yet by the 3rd and 4th centuries there were at least three independant text-types in use at Alexandria, Caesaria, and Constantinople. These two manuscripts clearly show a strong bias towards the Alexandrian text.

And more importantly, they are not really 'early' or primitive witnesses at all, but sophisticated products of contemporary scriptoriums, heavily edited according to the directives of their overseers, professionally executed, proof-read and corrected by a series of later scribes. No textual critic today can be comfortable naively relying upon the early text-critical efforts of an uncertain 4th century scriptorium with its own agenda.

Eusebius and Constantine especially are problematic 'witnesses' to the original text. Eusebius was far too sophisticated and partisan to be a reliable witness.

Constantine was a 'nominal' Christian at best, and people who disagreed with him tended to 'disappear'. Constantine boiled his own queen alive, and murdered his 'son', presumably over adultery, and can hardly be expected to have been in favour of our passage!

Eusebius wrote a fawning biography of Constantine, full of praise, but he left out this torture/murder (and some other things) entirely. It is easy to see how he might also have left out our passage when filling an order for 50 Bibles to be shipped to the Emperor.

"Fausta was the second wife of the Roman emperor Constantine. ...

Fausta was a young woman, not too many years older than Constantine's first - born son Crispus. Though Crispus' mother was one of Constantine's concubines, he had won the army's abiding affection because he was a popular and successful commander. Fausta evidently fell in love with the young man and tried to have an affair with him. When he refused her advances, she became indignant at his rejection of her and told Constantine that Crispus was the one who was making the improper advances.

Constantine became enraged and did not bother to check out the truth of the matter. He could not very well have Crispus executed in public because he was so popular, so Constantine had his son murdered in secret.

Helena, Constantine's mother suspected that Fausta was lying and had falsely accused Crispus of unfaithfulness. There were also rumors that Fausta was having an illicit affair with a slave. After she used her influence with her son to convince Constantine that he had acted hastily, the old emperor began to see that he had been lied to and had unjustly put his son to death.

Constantine now compounded the tragedy by having Fausta murdered. He instructed his servants to lock her in her bath and heat the water so much that she either boiled to death or was suffocated by the steam."

(from: http://www.crystalinks.com/romewomen2.html)

Return to footnote 8 reference above

9. "None of the Greek writing church fathers include it in their commentaries."

The reason Greek Commentaries on the scriptures in the Middle Ages left out commenting on John 8:1-11 is simple. The ancient commentaries were not commentaries in the sense we have today, where you go and buy one and take it home to read. They were public lessons commenting on what section of scripture was read during the service on a particular day.

Church Commentaries don't determine the canon of Scripture. They only comment on appropriate portions of it, and these scriptures actually have to be read aloud first, for the commentary to function and make any sense.

Many other passages, like Jude and all of Revelation were also left out of the normal public reading in church during the year, because they were not deemed appropriate to worship service. How Scriptures were chosen for public reading has to do with their content, not their authenticity. As a matter of fact, John 8:2-11 was chosen to be read on special Saint's Days in the later Lectionary system.

Return to footnote 9 reference above

10. "This shows that the early manuscripts simply didn't have the story."

Unfortunately, it doesn't show anything of the kind. Even if 'Greek speaking' commentators ignored or were ignorant of the story, this cannot magically sweep away a thousand years of Greek manuscript production which includes the verses.

At best one might remark on the oddness of this apparent omission by the existing Greek commentators. It would obviously be far more problematic to pose that virtually the entire Greek manuscript tradition from 500 to 1500 A.D. was a 'mirage' of some sort.

Return to footnote 10 reference above

11. "Well, in the Middle Ages, a scribe...wrote it down in the margin of a manuscript."

This scenario is extremely improbable. The passage takes up a column and a half (in smaller manuscripts a page and a half) of text. There were no 'wide-margin' editions of the Book of John. The rarity and high cost of vellum (goat or antelope skin for 'paper') for manuscripts prevented such decadence. Every square inch was valued and used within sensible bounds. An entire page or more would need to be erased, or added to an existing manuscript, or attached to the end, for a passage of this size to be 'inserted'.

It is true that some late (12th cent.) manuscripts actually do attach the entire passage to the end of John, in order to preserve it and provide means to restore the passage in the next copy. But this fact cannot support Ehrman's fantastic story: - In those manuscripts, the space was planned for and allocated in advance.

Even with a large Uncial Bible or NT, the remaining 3/4 or half-column of space between 'books' would be too small to fit the story into. So it could not have been added to an existing manuscript naturally or easily. It could never have been incorporated into the text from the margin, in some kind of accidental or confused manner.

A passage of this size could only be added by willful intent in a planned and systematic manner, motivated by a strong belief in its originality.

Return to footnote 11 reference above

12. "And from then on that manuscript got copied."

No. From then on there would be two versions of John: a small number of copies with the passage, and an overwhelming majority of copies without it, if Ehrman's theory were plausible. However, the manuscripts show the opposite case: there are an overwhelming majority of manuscripts with the passage, and only a handful without it!

Return to footnote 12 reference above

13. "that MSS was the copy used by the KJV translators "

No. In fact, the KJV translators of 1611 did not use any single copy of the Greek NT. They consulted a wide variety of evidences, including previous translations such as the Latin Vulgate, several previous translations into English, and many NT manuscripts available at that time and collected for the purpose. They also used printed editions of the Greek text made from a variety of collated manuscripts.

These scholars were also well aware of church history regarding the text used throughout the Middle Ages. They also would have been familiar with commentators on the passage, from Ambrose (360 A.D.) and Jerome (380 A.D.) to Calvin (1560 A.D.) The KJV translators were not at any time 'fooled' by a late copy of John with a story of adultery 'inserted by a Medieval happy-go-lucky scribe'.

Return to footnote 13 reference above

14. "it wouldn't have been known at all to Greek reading Christians in the ancient world "

Now there has been a quiet shift of eras and references. Ehrman was speaking about the Middle Ages. The listener would naturally assume we were still talking about the Middle Ages. But in fact, he has just lept back to the period between 100 and 300 A.D., the only period to which this statement could possibly apply.

But all his claims and assertions were about the other time period, the Middle Ages. He has produced no actual support for any statement about this very early time period. And that is because there simply isn't any reliable detailed information about this early period, particularly about this passage.

Return to footnote 14 reference above

15. "This story illustrates the point being made in John chapter 7 and 8."

Now incredibly, Ehrman embraces the opposite view to the one held by the majority of textual critics who reject the verses. They argue instead that the passage has little connection to the surrounding context and is an intrusion which breaks the natural flow of the narrative without it.

Ehrman here argues that the story has a natural context here between chapter 7 and 8. And he must, if he is to give any kind of plausible motive for its insertion here. It is not so much that Ehrman is wrong on this point, as that he undermines the current case for its status as an 'interpolation', in the process of accounting for its insertion in the first place.

Return to footnote 15 reference above

16. "Did the scribes have that much freedom that they could just add a story?"

Good question, and the short answer is no. The dangers of such a carefree attitude were severe and very real. Besides the thought of 'being struck from the Book of Life' by God Almighty, there was the obvious fact that copying was inspected by overseers. In an extended era where even a small heresy could result in being burnt at the stake, publicly drawn and quartered, or simply excommunicated or cast out of the monastery to fend for oneself, few scribes can be imagined to have risked losing their enviable jobs or lives just to insert a story that caught their fancy.

Return to footnote 16 reference above

17. "Its shocking to my students just how often these scribes would change their texts."

No doubt Ehrman's more gullible students could get that impression, spending most of their time upon a handful of Egyptian texts heavily edited by Alexandrian textual 'correctors'.

But its somewhat less shocking when we note that 'these scribes' are a small abberation, and that the majority of scribes elsewhere in the empire and throughout the Christian era did a careful job of copying, and resisted the urge to change their texts entirely. The plain uniformity of text extending from the 5th to the 15th century witnesses to the essential carefulness and reliability of most copyists.

Return to footnote 17 reference above

18. "Mistakes were replicated down through the line and so mistakes multiplied."

Except most mistakes were not replicated at all beyond a couple of copying generations before being caught by correctors. Only deliberate changes which had some plausibility would be perpetuated once a variation was noticed. In any case, this talk can hardly apply to the Pericope de Adultera, which could not have been spontaneously generated by a "copyist's error" or unconsciously assimilated by Christian scribes.

This prattle has nothing to do with the case under discussion, which must have been deliberately and consciously omitted or inserted in almost every manuscript where a scribe faced the problem.

Return to footnote 18 reference above

19. "Some scribes felt completely free to add stories, or take out stories."

Perhaps some did, but not in any surviving manuscripts of the New Testament that we know of. If such scribes existed, they would not have held their jobs for long. If by 'some scribes', Ehrman here means one out of ten thousand, it would be hard to refute the possibility. But serious discussion has now turned into absurdity with this ridiculous assertion.

If the Pericope de Adultera were such a case, it would be the only known case in the 2000 year history of copying the New Testament.

Return to footnote 19 reference above

20. "we know it happened is because we have these 1000's of surviving mss."

Only this is precisely what the thousands of surviving manuscripts don't show. No stories have been added or taken out at all, in the 5000+ manuscripts from all periods and in multiple languages.

The only thing remotely like this fanciful picture of scribes 'freely adding and subtracting stories', would be the variation in the Canon in some ancient Bibles or translations. That is, some translations excluded a few extra letters, like those of Clement, and some less popular books like Revelation were probably circulated separately.

The differences between the Greek Old Testament and the Hebrew text were an earlier (pre-Christian) Alexandrian Jewish creation, and they were simply inherited by the Christian scribes. They can hardly be accused of making up Maccabees, Ecclesiasticus, or the stories of Daniel.

The fact is, the Christian scribes were far more careful and accurate than the earlier Jewish scribes. This is demostrated both by the LXX and the Dead Sea scrolls, in spite of the fact that textual critics often claim the reverse, namely that Christian scribes were sloppier.

What is actually 'the striking thing about' the thousands of NT manuscripts is their incredible uniformity and agreement regarding the text of the New Testament.

Return to footnote 20 reference above

21. "thats a problem because we don't have the original texts, in many instances."

What has Ehrman been inhaling? We don't have the original texts in any instance, if by that he means autographed original letters by Paul or the evangelists. But that is not any new problem. That has been accepted by Christians since the 1st century, as far as we know.

Ehrman seems awfully concerned about the problems Christians have historically faced, for a man who has abandoned his own faith and proclaims himself an agnostic. Thanks for the help Bart, but I think we can limp by on our own for now.

Return to footnote 21 reference above

22. "a text that was clearly and certainly added later to the bible."

Only Ehrman has not shown that any story has been 'clearly and certainly added', except in his own mind. And we'll wait a long time for a demo, because instead of posing evidence, Ehrman seems only interested in posing 'problems'.

Return to footnote 22 reference above

23. "..these stories that were added later to the bible."

Ehrman's repetition here is no substitute for substance. But more remarkable is that now, 'stories' plural are assumed, when Ehrman hasn't even demonstrated satisfactorily that even one story has been 'clearly and certainly' added, or even subtracted, from the New Testament.

Return to footnote 23 reference above

24. "a problem that theologians probably need to work on a little bit"

Now Ehrman unveils a small theological project which apparently ought to be embarked upon immediately. Ehrman, from his lofty university throne, apparently gently chides 'theologians' to get busy on this problem. The view must be grand up there, allowing Ehrman the Agnostic to see more 'clearly and certainly' what needs doing.

But it is unlikely that Ehrman expects to reach theologians from a woman's talk show. More probably we have the posture of a 'fatherly figure' scolding his erring but well-meaning children, for the reassurance of his audience of largely female 'housewife' demographic. This will maximize book sales based upon the 'authority' figure motif.

Return to footnote 24 reference above

Return to Index

Summary

The listener is led to think the story was unknown by all the Greek fathers until the 12th century. But Burgon exposed the idiocy of that assertion back in 1886 by pointing out that from at least the 9th to the 14th century, any Greek father would have found the story in most of the available copies. (Burgon, Pericope de Adultera: , "Will anyone pretend that say, Theophylact, did not know of Jn 7:53-8:11? Why, in 19 out of 20 copies within his reach, the whole 12 verses must have been present.")

In fact, the 'story' is found in John in the majority of MSS from the 5th century to the 15th. Over 600 mss have the verses in their normal position without any note of doubt attached.

The Greek commentaries left out John 8:1-11 because they cannot comment upon what was never publicly read to the congregation. This meaningless fact has been presented as though it had significance for the textual question, but it has none.

The 'early MSS omitting the passage are NOT the 5000 Greek manuscripts from the 5th century onward to the 15th, but rather a handful of mss from Egypt along with codex Aleph and B.

The story could not have been copied 'accidentally from the margin in the Middle Ages.' Actually, if the story was 'added', it must have been added BEFORE THE 4th CENTURY, since it was found in many Greek and Latin MSS from that time forward, and was accepted as scripture by 90% of Christians all over the Civilized world.

The only 'Greek speaking Christians in the ancient world' who could have been unfamiliar with the passage would have been Egyptians in about 200 A.D., not the Greek scribes of Medieval Europe or the Byzantine Empire, as Ehrman has falsely implied.

THOSE European scribes knew all about the passage and copied it faithfully into just about every Greek mss of John made for the entire thousand year period that could credibly be labeled a part of 'the Middle Ages'. By 'ancient world' Ehrman must have now magically switched back to 2nd Century Egypt instead of Medieval Europe... how did that happen?

Question 4: "Can you explain a little bit more what might have led a scribe in the twelfth century to add this story?"

Its a great gag to set up the Interviewer to do your lying for you, then if you get caught you can blame her...hmmm. blame the woman...familiar?. But can Bart Ehrman the 'textual scholar' really 'blame the interviewer'? Are we supposed to assume that this clear question, phrased in just such a way as to summarize Ehrman's previous statement, was an oversight?

- That Ehrman didn't notice the inference that he himself had just created? Wasn't it Ehrman after all who was selling the idea of John 8:1-11 as an 'interpolation', and not the interviewer (who probably wouldn't know a monk from a monkey)?

Who is this 'Wormtongue', whispering goads of doubt, "yay, hath God said...?"

Of course, we listeners are just dumb enough to swallow a plug for the Da Vinci Code while we're here. "The professor mentioned it...it must be good." It is interesting to note that many Catholics are also suggesting we read the book or go see the movie... I wonder how much money these propagandists have invested in that as well...

Yes, and the most amazing thing about the 5000 surviving manuscripts is surely the hundreds of times that arbitrary stories are just added to and subtracted from the NT, about the size of a passage like John 8:1-11...I'm sure it happens all the time. Or wait - perhaps not at all...

I plumb forgot...did Ehrman actually clearly and certainly prove anything or just present a few 'facts' in the most misleading manner possible, even judged by the amazing shenanegans of 19th century critics?...

Return to Index

Conclusion

Perhaps Ehrman's Agnostic semi-God won't mind his shinanigans: After all, its hard to live off a University professor's salary of $100,000 /yr plus medical, dental, and retirement plans. Who doesn't need to suppliment his income with a few racey books about bible 'fraud'.

It may be that Ehrman as reasoned out something like the following argument: "God surely isn't going to be overly concerned with me for 'adulterating' John 8:1-11 - after all, he forgave the whoring adulteress, for crying out loud. What can He say after that?"

The problem is, not only is Ehrman a bad textual critic, he is also an awful expositor of bible stories. If he had interpreted the story of John 8:1-11 properly, he would have noticed that Jesus didn't 'forgive' the adulteress at all: He merely called an ajournment and put her on probation with conditions. Her sentence still hangs over her head.

Perhaps Jesus will be similarly merciful with Mr. Ehrman, and allow him adequate time to repent of this wilful and childish deception. The passage ends, after all, with

"Go and sin no more."

This is a note of hope, not condemnation. For 'sin no more' implies there is a point to obeying Jesus. There could be forgiveness at the end of that tunnel. Just as the example of the woman taken in adultery holds out hope yet as a 'type' of unbelieving Israel, so it also holds out hope for Bart Ehrman.

Perhaps its a bit hasty to cross out the Pericope de Adultera from Ehrman's 'bible' just yet.

Return to Index

DAILY SHOW INTERVIEW

Bart Ehrman appeared again, on The Daily Show with Jewish comedian Jon Stewart on Comedy Central on March 14, 2006 (with repeat casts on 15th etc.).

This interview is bizzare and abnormal on several levels, but not at all inexplicable.

(1) First of all, the Daily Show is not by any stretch of the imagination a serious 'current events' program, or any kind of educational or news broadcast. The normal fare is richly off-color humour pieces and most 'guests' are brought onstage for spectacle, ridicule, and ribald humour opportunities.

(2) Aside from being out of character for the show, the piece is also absurdly untimely. The book was published and printed back in early 2005, and here (late 2006) it is brought on as though it was a brand new release, not an obscure popularization of a boring academic subject of which the public is almost wholly ignorant, and careless of.

(3) Finally, the interviewer, Jewish comedian Jon Stewart suddenly takes on the role of a serious interviewer, praising the book and warmly welcoming Ehrman as a respected authority. Although he cracks a few jokes, they are not aimed at Ehrman or his book at all, but rather some obscure and harmless digs at the Gideon's Bible society. Most viewers are hardly likely to even pick up on the jokes, and a laugh-track is used for reinforcement. The dead air and boredom of the live audience is evident.

(4) Ehrman on the other hand is treated with such enthusiasm and even anticipation of what he will say, that its hard to grant Stewart any credibility as an unbiased or independant 'interviewer' at all. The shameless promotion of the book makes it clear that this is 100% a plug-piece for Ehrman.

We can hardly pass by on this without at least commenting on the cost alone. Even if Ehrman's book has been immensely over-popular, being pushed on best-seller lists, and promoted through the academic circuits, its not a news item, and needs no promotion this late in the game.

Modern book sales are carefully managed, and are based upon timely release and large marketing budgets. In fact, publishers estimate that 30-40% of book sales are a direct result of marketing and promotion. Even so, few books, even best-sellers ever get 10-20 minutes of Prime Time television on the hottest show on a major network.

Since no amount of profit from book sales or even movie futures (especially for this book) could possibly pay for let alone account for the huge amount of network airtime being devoted to the book, there really is only one explanation. Vested interests are promoting the book, just as was done for Charles Darwin, Harold Robbins, and countless other books that had a political currency far out of proportion to their actual contents.

North American Jewish lobbies have always relished taking shots at Christianity, especially fundamentalist Christianity. And Ehrman's book falls neatly into the category of undermining Christian interests. It is no surprise that Ehrman has acquired volumnous free airtime to promote a book that essentially slags the Holy Bible.

Even honest, conscientous Jewish analysts have documented this widespread attitude from North American Jewish interests for us. For instance, the Jewish domination of the p0rn industry, and the almost irrational psychological drive behind it is well documented, and can be found for instance here:

JQ: Anti-Christian Motive in Jewish Domination of P0rn <-- Click Here.

Bigtime Jewish comedians like Jon Stewart have no trouble at all inviting people like Ehrman onto their shows, shamelessly promoting their anti-Christian message, even if it cheats their own audiences out of the comedy they tuned in for. As long as it slams Christianity, its a free service.

In the nearly two years that Ehrman has had, fending off criticisms for his fraudulent presentations, one would hope to see some remorse, and some cleaning up of his act. But that is simply not the case.

Ehrman continues the same misleading propaganda war. But this time, he 'tag-teams' with his new Jewish sponsor, like in a corny American 'wrestling match'. It is painful to watch but easy to document.

The video clip can be found here:

The DAILY SHOW: Ehrman and Jon Stewart <-- Click Here to watch Video

Bart Ehrman on The Daily Show

The Daily Show March 14, 2006

Stewart: "Thank you very much for being here: first of all the book is called Misquoting Jesus, ah, and ah, its really...an amazing...book that teaches you things that you took for granted, that - that are wrong and I'll just start with - uh sort of the parable of Jesus and the Prostitute...and the crowd brings the prostitute to Jesus and says - you know - lets stone her, it was a test; he says "let he who is without sin cast the first stone", you say, "probably never happened". 25

Ehrman: "Ah, well: uh what I say is that uh in fact this story even - even though its the most popular story probably in the Gospels, ah - it wasn't originally in the Gospels. Uh Our oldest manuscripts of the Bible don't have this story. 26 So it looks like this was a story that was added by scribes, in later centuries, uh to the text. So it not only didn't happen probably it also wasn't originally in the Bible."

Stewart: "Why would they add it, would would people like give notes? Would they read a text of the Bible and say 'It needs some sex appeal!' "

Ehrman: "heh heh,", crowd snickers at 'sex appeal' ..

Stewart: " 'Uh....Give me a prostitute and some stones! (Ehrman: "hah hah") ...Make it work!' " (Ehrman: "right.") "You know - wu - wu why would they - why would they change things?"

Ehrman: "Well I - I think in this case they probably added the story because it taught - Jesus' teachings about love and mercy so well, and so this encapsulated some of the things Jesus had taught so somebody, took the story and put it - my - my guess is probably a scribe put it in the margin, of a manuscript and, at a later time some other scribe read this in the margin and they thought "Oh that belongs in the text" and then put it in the text, then that manuscript was copied and so we got it till - till today."

Stewart: "What's so interesting is the manner in which books were copied in the day lent itself to this recontextualizing, because people literally copied things." 27

Ehrman: "Right, well this was before the printing press and so the only way to get a book reproduced in the ancient world was to copy it, one word, one letter at a time, and the problem is when scribes were copying these texts they meh- made mistakes. Sometimes they would just - m- mispell a word or make some other ac-accidental mistake, but sometimes they would actually change the text and make it say what they wanted it to say, and so we have these thousands of manuscripts of the New Testament, we have over 5000 of these manuscripts, but no two of them are exactly alike. There are hundreds of thousands of differences in these manuscripts, and so the task is to figure out what did the author actually write, given the fact that we don't have the originals."

Stewart: "Now which one has primacy? Is it the one, ...in my hotel room?" (pause, canned laugh-track laughs aloud approvingly)

Ehrman: "Yeh Yes, that thats the uh thats the authentic version." (sarcastically playing along, laugh-track punctuates banter)

Stewart: "That's the authentic version! That's the other mystery!"

Ehrman: "Yes."

Stewart: "How do they get em in all the hotel rooms?"

Ehrman: "Ha ha ha ha ha!" (guffaws out loud) "Yes, yes:"

Stewart: "They just show up one day and...they slip em into everybody's uh - the the idea that - the Bible then - y- y- you were someone that went through sort of a period of discovery - you - you - were a literalist I guess, or - or 'born again' you would say? and then as you studied and learned more about it you began to question that."

Ehrman: "Right. I - I started out uh, being interested in the Bible because I was a born-again Christian a fundamentalist who thought that the very words of the Bible had been given by God, and so I, I studied Greek in college, and decided to read the New Testament in Greek 'cause..."

Stewart: "That was the original language..."

Ehrman: "that was the original language that it was written in and so uh the more I studied the the the more I saw there is an enormous problem - we don't have the original - Greek copies of any of these books, all we have are these...thousands, these thousands of manuscripts from centuries later, that have all these changes in them, and so this uh realising that we didn't have the original and that we - that some - places we don't know what the original said, that it had quite a profound on my, my faith that these words had been given by God."

Stewart: "Now what does that do, because to my mind, as I read your book and learned more about it, the Bible, - not that it wasn't interesting before, suddenly became more interesting to me."

Ehrman: "Yeah"

Stewart: "...in that it - it - I felt like that information doesn't denigrate the Bible in any way but brings it to life in a manner - it suddenly becomes... a living document that ch - you know sort of that Heisenberg principle it - it is changed by whoever it passes through, which suddenly makes it seem more,... almost more Godly in some respects."

Ehrman: "uh yeah eh its an interesting point because eh f - for me the the Bible takes on new life when we see that the Bible is a living thing, and that it isn't a - a dead document that was written, 2000 years ago, but as, as scribes copied the text in a sense they were interpreting the text and putting their interpretations, into the text. Wha wha while they did that, uh, for me, I found it to be a liberating experience to realise this in part because realised that the bible was not only copied by human scribes, it was written by human authors, and these authors all had different points of view, different perspectives different ideas, and they put all those different views, points, uh points of view, in the text itself..."

Stewart: "And mostly shaped it during that 300 years, between sort of uh uh Christ's death and when, uh, I guess Constantine converted an- and Rome converted and Christianity became sort of the law of the land."

Ehrman: "Right, so the - the authors of the New Testament were writing mainly in the 1st century but then their books were copied by these scribes over this - over those centuries..."

Stewart: "Right, and those are the Gospels."

Ehrman: "Those are the Gospels of the New Testament Matthew Mark Luke and John, and..."

Stewart: "Why would God send his original text in Greek?"

Ehrman: "..ha..Why would (*cough) God send His text in Greek. (canned laughter)...uh, yeah its a good question I think just to keep Greek professors employed, I, I don't really know."

Stewart: "ha ha ha ha! (canned laughter) Its the only way that keeps em in there..."

Ehrman: "ha..yes..right" (overtop Stewart).

Stewart: "Ah. - it really is, uh I have to say, it was just one of the most interesting things I've read about a book that - that is in itself timeless and I really congratulate - its a hell of a book. - and I don't say hell of a bible." (loud canned laughter)

Erhman: "ha ha!"

Stewart: "I clearly, - I'm an idiot - ah, 'Misquoting Jesus' is on the bookshelves now Bart Ehrman thanks for joining us."

Ehrman: "Thank you."

Return to Index

Footnotes:

25. Stewart manages to make three severe errors in his opening sentence: (1) The section is not a parable. (2) The woman was not a prostitute, but a woman caught in adultery. (3) The crowd did not bring the woman to Jesus. The Jewish leaders, namely the Pharisees and Jewish Lawyers (called 'scribes' in NT times. some MSS actually have 'archpriests').

This is the very section he chooses to open with, probably at the prompting of Ehrman, and these can hardly be 'mistakes'. This passage is an order of magnitude more offensive to many modern Jews than any other part of the New Testament. Its the only part in the New Testament that witnesses to the Jewish leaders actually in the act of murdering a woman in order to frame Jesus.

Most other attacks upon Jewish authorities in the NT revolve around the interpretation of the Law, or regarding Jesus' status. Modern Jews are not 'offended' as much by these passages, since they feel the Jewish position is quite defensible, and a matter of their own religion.

In fact, the passage was probably removed from some MSS in the first place for this very reason, by Jewish professional scribes back in Egypt in the 2nd century.

Return to footnote 25 reference above

26. Here Ehrman pulls the same old tricks. He provides no new information at all to the millions of viewers willing to listen. Instead he recites what they already have at home in the footnote of every modern bible. Ehrman, with bookloads of little-known textual information on these verses, gives the audience nothing at all. He leaves them hopelessly misled by his ridiculous simplification of the textual evidence and problem, and gives a simpleton's explanation of the omission.

One might think that the reason is that Ehrman is saving all the evidence and argument for his book. All this emphasis on John 8:1-11 (The Pericope de Adultera) leads one to expect several chapters, or perhaps at least a good extensive section giving a treatment of the complex evidences.

But no. The buyer will be disappointed to discover once again, there is nothing in the book at all on the textual problem of the Woman Taken in Adultery. In fact, it is only briefly treated in passing on page 65-66, where Ehrman merely reiterates his fantasy about it being copied in a margin, and mentions its absence in the oldest MSS. He completely skips out of the obligation to show his evidences.

Return to footnote 26 reference above

27. Suddenly Stewart sounds like a text-critical expert. Or perhaps just like Ehrman. While we don't doubt Stewart's intelligence and education, this statement is so out of character and deadpan that we have to suspect its a line from either Ehrman or the book. Luckily Stewart quickly falls back into his comedian/actor persona, or else the show would tilt into the 4th dimension or morph into an episode of the Twilight Zone.

Return to footnote 27 reference above

Return to Index

COLBERT REPORT INTERVIEW

Ehrman again appeared on June 22/2006 on the spin-off comedy show that came from the DAILY SHOW, called the COLBERT REPORT. This is again quite clearly a comedy show, and not a serious talk-show or news program.

COLBERT REPORT: Bart Ehrman Interview

Once again Ehrman disappoints by providing the audience with nothing accurate, interesting, or new regarding the complex evidence concerning John 8:1-11.

The naive listener might think here Ehrman is finally getting drilled for his off-color views about the Bible. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Colbert the Joker

Colbert is no idiot, or fundamentalist. He is a sophisticated actor who has been honing his comedy skills for a long time. His specialty is playing the buffoon / everyman. One of his favourite characters is his 'Christian fundamentalist'.

He presents a front of being a 'serious Catholic', that is, a kind of naive bible-believer who stumps the scientists for all the wrong reasons. Here Colbert is once more playing a character he has used extensively for laughs.

Colbert is a comedy actor of the 'Shakespeare' school. That is, he deliberately speaks different things to different layers of the crowd. He appeases the masses with low-brow humour, while allowing the more intelligent listeners to see through the facade to the 'real joke'. In this he is far superior to Stewart, who is just a clever clown.

The real gag here, from Colbert's and other insiders' view is the irony of the 'Bible' being true because it says it is, a circular argument which is very popular with naive fundamentalists and preachers, but one which is well known and utterly discredited as far as sophisticated agnostics, philosophers and scientists are concerned. Colbert is constantly speaking through two mouths, and Ehrman is in on the gag.

It is also likely that Ehrman 'one-upping' Colbert at the end regarding the crude joke about 'balls' was preplanned and probably written into the script by Colbert.

Goodacre on the Interviews

Mark Goodacre is not impressed with Colbert's humour:

"...it doesn't make easy watching. I'd say Colbert's tactics back-fired rather. If he is attempting to make fun of fundamentalist Christians, it certainly doesn't work. If he is attempting to make fun of Ehrman, then it just comes across as bullying. ... I must admit that I'd take Jon Stewart over the irritating Colbert every day of the week. Stewart's interview with Ehrman a few weeks ago was a model of how to engage intelligently, by contrast."

(Goodacre, http://www.ntgateway.com/weblog/2006/06/bart-ehrman-on-colbert-report.html)

Yet it seems Goodacre doesn't quite understand what the interview on the Daily Show with Stewart was really all about. (see above).

Ehrman's Obsession with John 8:1-11

What is most disturbing and of concern is that again Ehrman seems to be obsessing on John 8:1-11. Again at least one third of the interview is about the Pericope de Adultera, and this has been carefully crafted by Ehrman. Yet Ehrman's book isn't even about the Woman Taken in Adultery!

He only devotes a page and a half to the subject in the book, and in fact there is less information in the book than he gave in his first radio interview. The book is just a very short summary of what he spoke of in far more detail over the radio. There is no technical discussion at all about the evidence surrounding the passage, and one will find more information in the footnotes of the UBS Greek text than in Ehrman's book.

Bart Ehrman on The Colbert Report

The Colbert Report June 22, 2006

Colbert: "My guest tonight is a theologian and the author of 'Misquoting Jesus'. In the words of the Prophets, 'Let's get ready to rumble!' Please welcome Bart Ehrman

(intro music, cheers...as the two take a seat)

Colbert: "Mister Ehrman, Dr. Ehrman, Doctor?"

Ehrman: "Doctor."

Colbert: "Doctor. Ehrman okay; ...Let me lay my cards on the table here. I believe that the Bible is inerrant, without flaw, and directly from the mouth of God. Let's have a reasonable discussion." (pauses for laughs from audience.) What do you mean by 'Misquoting Jesus: the story behind who changed the bible, and why', What do you mean the the Bible changed? The Bible's from God, God doesn't change."

Ehrman: "Yeah well the problem is, that the uh, the we don't have the original manuscripts of any of the books of the Bible; what we have are - copies made many centuries later and all these copies have differences in them."

Colbert: "Why would we want the original I mean thats just a first draft. We've got the one they got right."(Ehrman: "uh...") I'm sure the first draft of the Gettysburg Address had a lot of 'um's and 'uh's in it."

Ehrman: "Right."

Colbert: "Right."

Ehrman: "Right. So uh..."

Colbert: "So wh what do you say what do you say we don't have the the first draft. I mean this the this is what happened, wha what happened in the Bible is what happened in Jesus'es life, right?"

Ehrman: "Uh, well it may have been but the problem is we don't have the originals and these copies that we have, these thousands of copies are all different from one another, so, not only did they not get it right to begin with, the scribes didn't get it right all along the way so.."

Colbert: "Now wait a sec wait a second, how do you know they didn't get it right to begin with, how do you, - a let's take the Gospel of Mark, its often thought thats the first one written?"

Ehrman: "Thats Right."

Colbert: "Okay? About what, 60-70 A.D. they think maybe, somebody said 70 A.D.? (Ehrman: "yes.") "How do you know they didn't get it right?"(Ehrman: "ah well...") "I mean they are a lot closer to the events than you are sir." (laughs from crowd)

Ehrman: "Yes they are. (pause for laughs to subside) Well, so maybe they did get it right. The problem is..."

Colbert: (cuts him off:) "Okay, so you're wrong on that one, go on." (laughs from crowd..)

Ehrman: "Right. ... But even if they did get it right,(Colbert: "Okay:") the problem is we don't have Mark's writing, (Colbert: "mm hmm:") what we have are copies of Mark's writing from hundreds of years later, (Colbert: "mm hmm:") and these copies that we have of Mark's writings don't agree with one another: So there are hundreds of thousands of differences among these manuscripts that we have of the New Testament. ...

Colbert: "Look: Do you believe that there's a God?"

Ehrman: "I'm not sure."

Colbert: "Really!"

Ehrman: "Yeah."

Colbert: "So... you're an agnostic."

Ehrman: "That's right."

Colbert: "Isn't that just an atheist without balls?" (big laughs from crowd...dies down)

Colbert: "Cause if I were an atheist I'd be able to look to God and say, 'Sorry, -don't exist, sir.'"

Ehrman: "uh huh."

Colbert: "Right?"

Ehrman: "Yes, you would."

Colbert: "Okay! ....So, like but if there is a God, go with me here: (Ehrman: "alright.") If there is a God: Wouldn't God make sure the right copy got copied? "

Ehrman: "Yeah. ah right you would think so."

Colbert: "I do think so!"

Ehrman: "Well - the problem is, we don't have the copy. So, if God did preserve a copy for us, which of the copies is it?"

Colbert: "The one in my Bible."

Ehrman: "Yes." (...laughs from crowd)

Colbert: "I mean I don't know how to put that any clearer. "

Ehrman: "Yes. Well -"

Colbert: "The Bible is without flaw, and the Bible is true, because the Bible says the Bible is true. Is there some part of that logic you don't get?" (big laughs from audience)

Ehrman: "Yeah. ...uh The problem is that these verses that - that you might quote to say the Bible is true..."

Colbert:"Give me an example, like you - you mention here, 'Let he who is without the - without sin cast the first stone.' (Colbert jumps to John 8:1-11)

Ehrman: "Right."

Colbert: "So wha- what thats misquoted?"

Ehrman: "Uh, well the problem is that - thats a story about Jesus and the woman taken in adultery, where this woman (Colbert: "Right") is brought to her and - and - uh should we stone her or not - Jesus says 'Let the one without sin -' the problem is that story is not found in our oldest manuscripts of the Gospel of John, 28 or or in any of our Gospels: Uh, the early commentators on the Bible don't mention this story until a thousand years after John was written. 29 So this is a story that wasn't originally in the Bible - this is a story that was added by later scribes."

Colbert: "Now - mm Let me put it this way - Clinton never said 'I feel your pain', (laughs from crowd...) it doesn't mean he didn't. Okay?"

Ehrman: "That's true."

Colbert: "Right...." (Great laughter as dirty joke dawns on crowd) ...so ...even if Jesus never s- said that, it doesn't mean its not part and parcel with the message of Jesus, right?..."

Ehrman: "That's true too."

Colbert: "So it - it's true it fits everything else,...

Ehrman: "Right, well alot of things fit..." (overtop Colbert)

Colbert: "The evidence would say that he probably, said something like that, if he didn't say it. ..."